The Union League of North Carolina was an affiliate of the Loyal League of America, which is believed to have been created in early 1862 by Judge James M. Edmunds of Philadelphia as a patriotic club directed by the Republican Party. Branches quickly formed in New York, Boston, and other cities, and by late 1862 these bodies had created a National Council of Leagues to assist the Republican Party in retaining voter support. The National Council took part in President Abraham Lincoln's reelection drive in 1864 and encouraged the growth of Unionist sentiment among middle and lower class southern whites who wished to return to the Union and among enslaved and free black people who could be weaned from assisting the Confederacy. In 1864 Loyal League organizers appeared in West Virginia, eastern Tennessee, and parts of coastal South Carolina and North Carolina, areas already controlled by Federal troops, to form local Union Leagues.

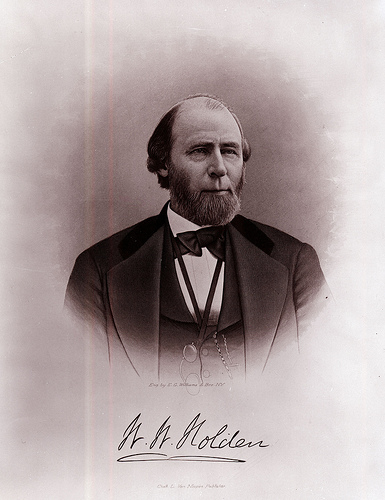

On 4 July 1865, 2,000 Union Leaguers marched in Raleigh's Independence Day celebration and cheered North Carolina provisional governor William W. Holden, who was known to look favorably on poor white and black concerns. Later that evening, Holden "enthusiastically" received league members and local freedmen at his home. The winter of 1866-67 heightened the political tempo as the national Republican Party swept the fall elections and gained control of Congress. By announcing its intention to grant blacks the vote as well as political and social equality, Congress effectively took over Reconstruction from President Andrew Johnson. In North Carolina, Holden, who had already begun to organize an independent political movement, committed to black equality in January 1867; two months later, after the announcement of Congressional Reconstruction, he launched a state Republican Party.

North Carolina Union Leaguers resisted party control and sought to rule the state organization through the leagues. Since the leagues were at least 80 percent black and represented nearly 40 percent of the state's population that was of African descent, its support was essential for victory. Yet Holden realized that success was equally contingent on a sizable turnout of whites who had difficulty accepting black equality. Accordingly, the governor moved carefully, but by the fall of 1867 he had merged blacks and whites into the state Republican Party, had himself elected as its chair, and reduced the leagues to a component of the party.

Holden worked tirelessly for the Republican Party during 1867 and 1868. New leagues were recruited and old ones strengthened until almost every midland and eastern county supported 2,000 or more leaguers. The Ku Klux Klan soon challenged Holden's efforts. It struck at the basis of his power-the Union Leagues and their leaders-vowing to remove the "dark savages and white ignoramuses wearing the oath of office." Their intimidation was so thorough that many leagues ceased to function and thousands of blacks failed to vote in November 1870. After impeachment charges were brought against him, Holden was tried and removed from office on 22 Mar. 1871. With his fall and the steady pressure of the Ku Klux Klan, the Union Leagues collapsed.