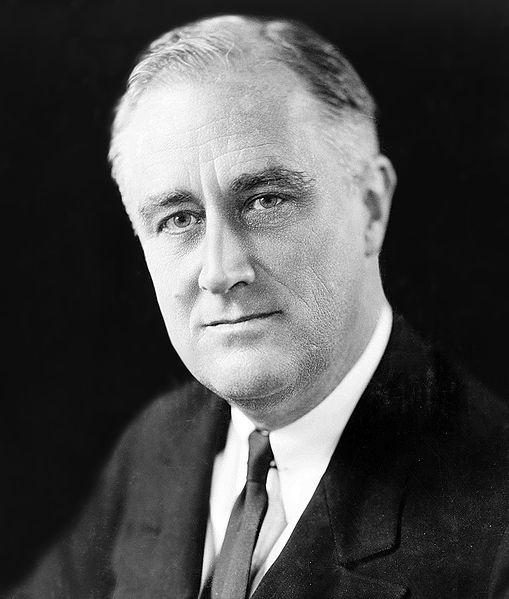

Before Roosevelt's second term was well under way, his domestic program was overshadowed by the expansionist designs of totalitarian regimes in Japan, Italy, and Germany. In 1931 Japan had invaded Manchuria, crushed Chinese resistance, and set up the puppet state of Manchukuo. Italy, under Benito Mussolini, enlarged its boundaries in Libya and in 1935 conquered Ethiopia. Germany, under Nazi leader Adolf Hitler, militarized its economy and reoccupied the Rhineland (demilitarized by the Treaty of Versailles) in 1936. In 1938, Hitler incorporated Austria into the German Reich and demanded cession of the German-speaking Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia. By then, war seemed imminent.

The United States, disillusioned by the failure of the crusade for democracy in World War I, announced that in no circumstances could any country involved in the conflict look to it for aid. Neutrality legislation, enacted piecemeal from 1935 to 1937, prohibited trade in arms with any warring nations, required cash for all other commodities, and forbade American flag merchant ships from carrying those goods. The objective was to prevent, at almost any cost, the involvement of the United States in a foreign war.

With the Nazi conquest of Poland in 1939 and the outbreak of World War II, isolationist sentiment increased, even though Americans clearly favored the victims of Hitler's aggression and supported the Allied democracies, Britain and France. Roosevelt could only wait until public opinion regarding U.S. involvement was altered by events.

After the fall of France and the beginning of the German air war against Britain in mid-1940, the debate intensified between those in the United States who favored aiding the democracies and the antiwar faction known as the isolationists. Roosevelt did what he could to nudge public opinion toward intervention. The United States joined Canada in a Mutual Board of Defense, and aligned with the Latin American republics in extending collective protection to the nations in the Western Hemisphere.

Congress, confronted with the mounting crisis, voted immense sums for rearmament, and in September 1940 passed the first peacetime conscription bill ever enacted in the United States. In that month also, Roosevelt concluded a daring executive agreement with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The United States gave the British Navy 50 "overage" destroyers in return for British air and naval bases in Newfoundland and the North Atlantic.

The 1940 presidential election campaign demonstrated that the isolationists, while vocal, were a minority. Roosevelt's Republican opponent, Wendell Wilkie, leaned toward intervention. Thus the November election yielded another majority for the president, making Roosevelt the first, and last, U. S. chief executive to be elected to a third term.

In early 1941, Roosevelt got Congress to approve the Lend-Lease Program, which enabled him to transfer arms and equipment to any nation (notably Great Britain, later the Soviet Union and China) deemed vital to the defense of the United States. Total Lend-Lease aid by war's end would amount to more than $50,000 million.

Most remarkably, in August, he met with Prime Minister Churchill off the coast of Newfoundland. The two leaders issued a "joint statement of war aims," which they called the Atlantic Charter. Bearing a remarkable resemblance to Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points, it called for these objectives: no territorial aggrandizement; no territorial changes without the consent of the people concerned; the right of all people to choose their own form of government; the restoration of self-government to those deprived of it; economic collaboration between all nations; freedom from war, from fear, and from want for all peoples; freedom of the seas; and the abandonment of the use of force as an instrument of international policy.

America was now neutral in name only.

Japan, Pearl Harbor, and war

While most Americans anxiously watched the course of the European war, tension mounted in Asia. Taking advantage of an opportunity to improve its strategic position, Japan boldly announced a "new order" in which it would exercise hegemony over all of the Pacific. Battling for survival against Nazi Germany, Britain was unable to resist, abandoning its concession in Shanghai and temporarily closing the Chinese supply route from Burma. In the summer of 1940, Japan won permission from the weak Vichy government in France to use airfields in northern Indochina (North Vietnam). That September the Japanese formally joined the Rome-Berlin Axis. The United States countered with an embargo on the export of scrap iron to Japan.

In July 1941 the Japanese occupied southern Indochina (South Vietnam), signaling a probable move southward toward the oil, tin, and rubber of British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies. The United States, in response, froze Japanese assets and initiated an embargo on the one commodity Japan needed above all others - oil.

General Hideki Tojo became prime minister of Japan that October. In mid-November, he sent a special envoy to the United States to meet with Secretary of State Cordell Hull. Among other things, Japan demanded that the United States release Japanese assets and stop U.S. naval expansion in the Pacific. Hull countered with a proposal for Japanese withdrawal from all its conquests. The swift Japanese rejection on December 1 left the talks stalemated.

On the morning of December 7, Japanese carrier-based planes executed a devastating surprise attack against the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

Twenty-one ships were destroyed or temporarily disabled; 323 aircraft were destroyed or damaged; 2,388 soldiers, sailors, and civilians were killed. However, the U.S. aircraft carriers that would play such a critical role in the ensuing naval war in the Pacific were at sea and not anchored at Pearl Harbor.

American opinion, still divided about the war in Europe, was unified overnight by what President Roosevelt called "a day that will live in infamy." On December 8, Congress declared a state of war with Japan; three days later Germany and Italy declared war on the United States.

Mobilization for total war

The nation rapidly geared itself for mobilization of its people and its entire industrial capacity. Over the next three-and-a-half years, war industry achieved staggering production goals - 300,000 aircraft, 5,000 cargo ships, 60,000 landing craft, 86,000 tanks. Women workers, exemplified by "Rosie the Riveter," played a bigger part in industrial production than ever before. Total strength of the U.S. armed forces at the end of the war was more than 12 million. All the nation's activities - farming, manufacturing, mining, trade, labor, investment, communications, even education and cultural undertakings - were in some fashion brought under new and enlarged controls.

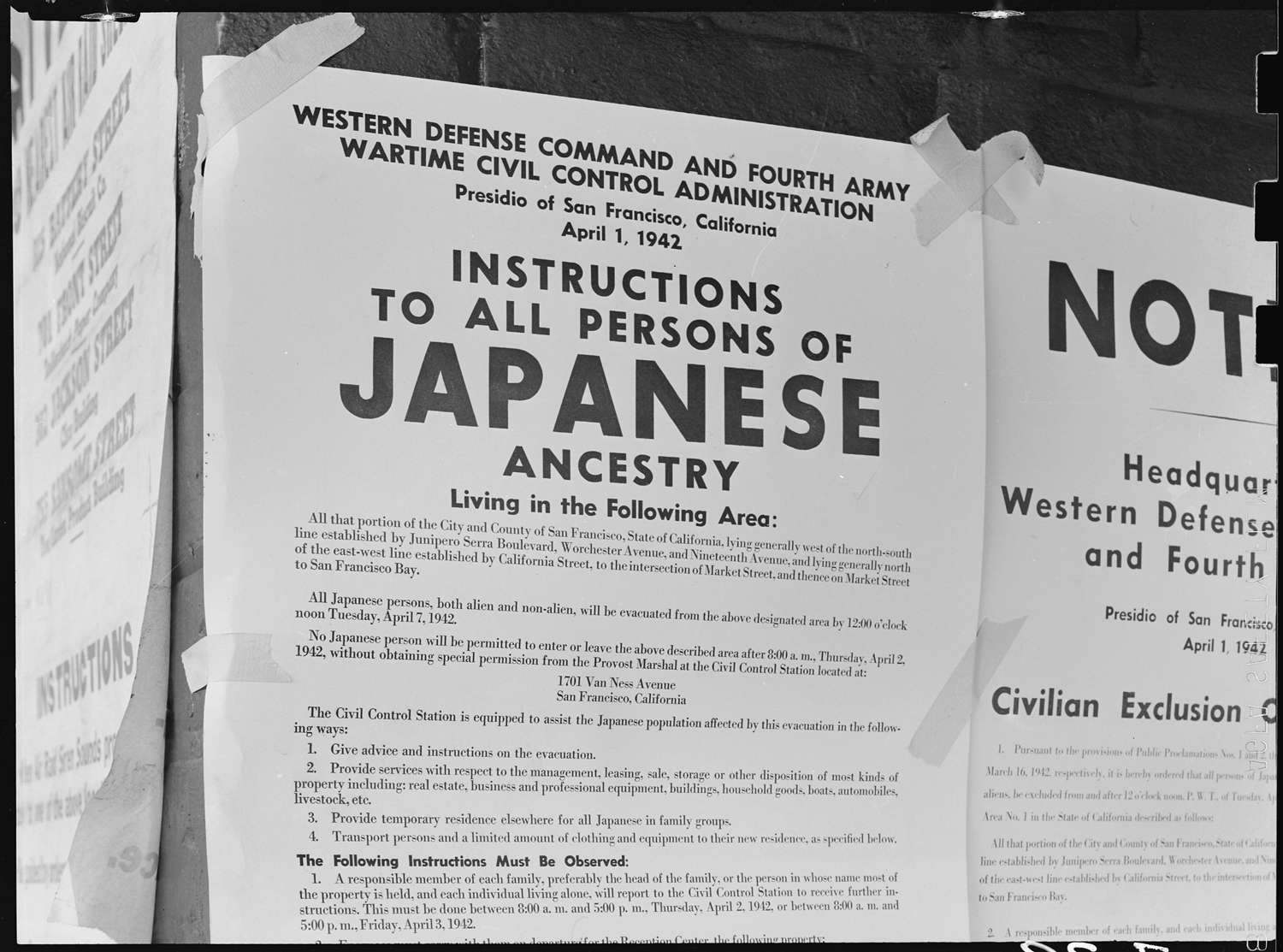

As a result of Pearl Harbor and the fear of Asian espionage, Americans also committed what was later recognized as an act of intolerance: the internment of Japanese Americans. In February 1942, nearly 120,000 Japanese Americans residing in California were removed from their homes and interned behind barbed wire in 10 wretched temporary camps, later to be moved to "relocation centers" outside isolated Southwestern towns.

Nearly 63 percent of these Japanese Americans were American-born U.S. citizens. A few were Japanese sympathizers, but no evidence of espionage ever surfaced. Others volunteered for the U.S. Army and fought with distinction and valor in two infantry units on the Italian front. Some served as interpreters and translators in the Pacific.

In 1983 the U.S. government acknowledged the injustice of internment with limited payments to those Japanese Americans of that era who were still living.