In 1876, the Republican Party of the late President Abraham Lincoln (nicknamed the Grand Old Party, or GOP) had dominated the presidency for 16 years, but GOP control was in jeopardy. The country was mired in a severe economic depression for the fourth year in a row. President Ulysses S. Grant was retiring after two terms dominated by a succession of political scandals. The Democrats, once disgraced by their Civil War association with the rebellious South, had regained strength and confidence, winning a majority in the House of Representatives in 1874. And white southern voters were demanding the withdrawal of federal troops stationed in the former Confederacy to enforce Reconstruction, the federal government's policy for guaranteeing political rights to formerly enslaved people and safeguarding Republican state governments imposed after the war.

Meeting in their national conventions, the Democrats nominated Governor Samuel Tilden of New York for president, while the Republicans picked Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes. Both men had reputations as reformers, and the two parties offered similar platforms advocating honest government and civil service reform. The general election campaign was dominated by mudslinging and by charge and countercharge, while the nominees remained above the fray, leaving attack politics to surrogates and the highly partisan newspapers of the day.

More than eight million voters turned out on election day, November 7. By evening, results arriving by telegraph showed a strong Democratic trend. Republican strongholds fell to Tilden, and by morning, he appeared to have won 17 states by a popular vote margin of at least 250,000, for 184 electoral votes, at that time just one short of a majority. Hayes was behind with 18 states and 165 electoral votes, but Republican Party hopes revived when returns showed narrow leads for Hayes in Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina, which controlled 19 votes. Local Democrats disputed the results, asserting that federal troops had tainted the election; the GOP countered with claims that black Republican voters had been kept from the polls by force in many places. Bitterly divided, each state sent two contradictory certificates of election results to Congress.

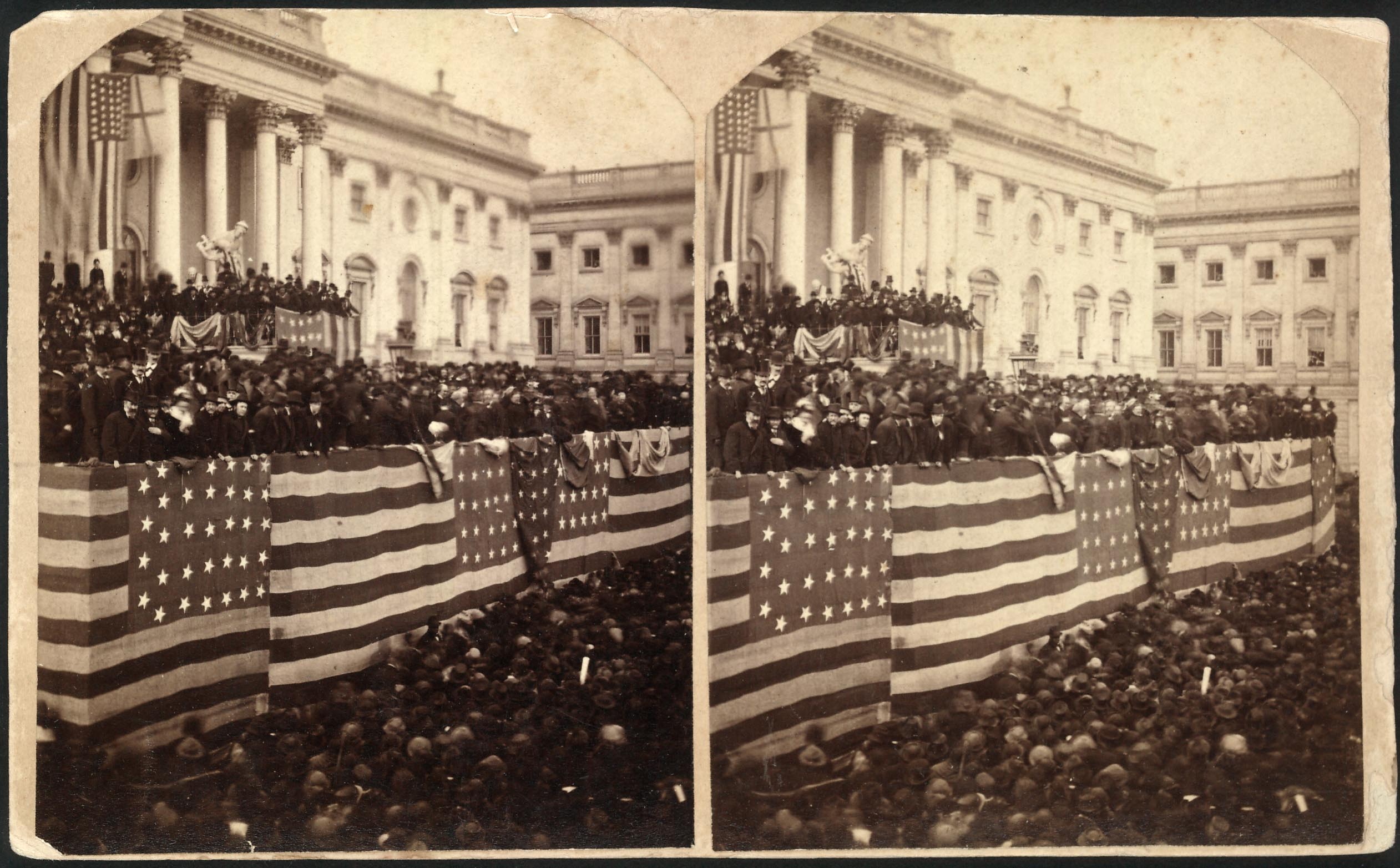

A fierce battle over the disputed returns was predicted, with supporters of both candidates threatening violence. Congress responded in January 1877 by establishing a bipartisan electoral commission made up of senators, representatives, and Supreme Court justices. The commission would determine which slate of disputed electors had the better claim. On February 1, Congress met to count the electoral votes; the disputed returns were referred to the commission, which painstakingly examined each of them. The process continued for more than a month, but in every case the commission voted by the narrowest margin to accept the Republican electors. On March 2, the last votes were awarded to Hayes, who was declared elected by a one-vote margin, 185 to Tilden's 184.

Despite widespread discontent among Democrats, the streets remained quiet: Over the previous month, party political operatives had worked out an agreement behind closed doors, the Compromise of 1877. Tilden and the Democratic Party accepted a GOP victory, while Hayes pledged to withdraw federal troops from the states of the former Confederacy, effectively ending Reconstruction. With the departure of the army, Republican governments in the South fell as formerly enslaved, now free, black people were prevented from voting by legal maneuvers, intimidation, and terrorism. Loss of the vote was quickly followed by segregation laws and other discrimination against black Americans, and it would be roughly ninety years before the nation redressed the legacy of 1877.