The authorities couldn't tell for certain who shot Gastonia, N.C. police chief Orville Aderholt on June 7, 1929, so they arrested nearly everyone at the scene. Seventy-one people were detained, all of them organizers for or members of the National Textile Workers Union, whose camp Aderholt was visiting when he was killed. The trial received national attention. Members of the media, like many locals, were divided as to whether the strike at the Loray Mill, which had begun earlier that spring, represented an honest effort by workers to improve their conditions or a dangerous plot by Northern Communists to infiltrate the South.

The textile industry in North Carolina was booming in the first decades of the 20th-century. New mills opened all over the Piedmont while old ones expanded. Investors from other parts of the country poured money into the region, taking advantage of one of the South's most important resources: cheap and abundant labor. The authors of a pamphlet issued by the Seaboard Air Line Railway around 1924 made a compelling case for bringing textile businesses south. "Labor is the South's greatest inducement to the textile industry," they wrote. "It would be difficult to find in any industry in the north or west more intelligent people than those comprising the operatives of our southern mills." Workers in the region, they claimed, faced longer hours, less pay, raised much of their own food, were protected by fewer labor laws, and even needed less clothing than their counterparts in Northern states.

By the late 1920s, mill owners faced increased competition and a declining economy. They tried to cut down on costs by applying the new principles of scientific management, reducing the labor force by ensuring that each worker was as efficient as possible. This practice of requiring more work in the same time period period without raising (and often reducing) pay was known by mill workers as "the stretch-out."

Union organizers saw the textile industry as the perfect place to gain a foothold in a region that had previously resisted organized labor. The National Textile Workers Union (NTWU), formed in Massachusetts in 1928, planned to start its work in the South with one mill in North Carolina, in hopes that a single strike would inspire sympathetic walkouts at other mills throughout the state. Fred Beal, an NTWU organizer, arrived in the North Carolina in early 1929 and began to look for a mill where labor conditions were poor enough, and workers were eager enough, to form a union. By the spring of that year, he had found it.

The Loray Mill in Gastonia was one of the largest in the state. The size of the mill, and the fact that it was owned by a textile company in Rhode Island, led Beal and others to believe that workers at Loray might respond to a call for unionization. Many workers did join the union, and the company responded by firing five union members in late May 1929. In response to the firings, the union members voted to strike. On April 1, close to 1,800 workers refused to return to the mill until their demands were met. The mill owners refused to negotiate, and by the end of the month, many of the strikers could not hold out any longer and returned to work. But that didn't mean that the troubles were over.

A few hundred workers remained on the picket line even after being evicted from their mill-owned homes and forced to live in a tent village put up by the union. There were frequent scuffles between strikers and local men who were sworn in as deputies solely for the purpose of subduing them. The hostilities reached their apex on June 7, 1929, when deputies broke up a picket line composed largely of women and children. The deputies and other police officers then went to the tent village, shots were fired, and the Gastonia police chief, Orville F. Aderholt, was killed.

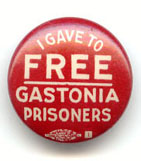

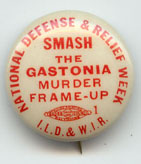

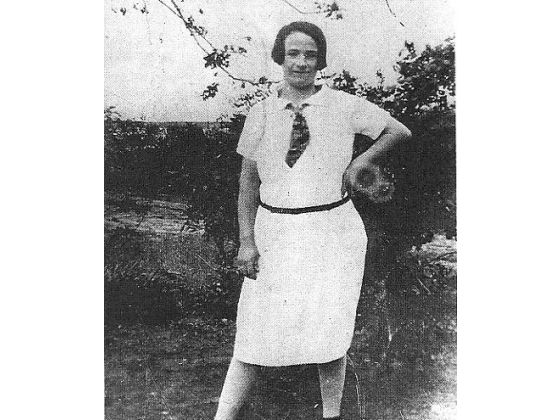

Sixteen union members were tried for the murder of Aderholt and were released when a mistrial was declared in September 1929. The troubles in Gastonia continued. At a large rally of union workers on September 14, 1929, Ella May Wiggins, a popular speaker known for her ballads in support of working women, was killed. Wiggins' death helped bring attention and sympathy to the plight of the mill workers, but it was not enough to secure a victory for the unions. Although workers received some relief from federal and state legislation in the 1930s, employers were successful in keeping unions out of the state, a legacy that has continued to the present. As of 2003, only 3.1 percent of North Carolina's workers were members of unions, the lowest representation in the United States.

Ella Mae Wiggins and the Loray Mill Strike

Ella Mae Wiggins and the Loray Mill Strike