North Carolinians reacted with sadness and concern when Germany invaded neighboring Poland on September 1, 1939. A new world war had begun. The Germans used blitzkrieg, or "lightning war," tactics — quickly destroying the Polish armed forces with surprise tank and aircraft attacks. Great Britain and France declared war on Germany but were unable to help Poland. In the spring of 1940, Adolf Hitler, the German leader, unleashed blitzkrieg on Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. By midsummer 1940, Western Europe had been conquered, and only Great Britain stood against Hitler's legions. Meanwhile, in the Far East, the Japanese army continued the conquest of China that it had begun in 1937.

These upsetting events alarmed Americans, including North Carolinians, but most were not eager to fight another war on foreign shores. Embittered by the experience of World War I and the failure of Europeans to maintain peace, they were content to stay behind the great ocean frontiers that they felt protected them from attack. Some Americans, notably President Franklin D. Roosevelt, saw danger in German and Japanese aggression, and the president worked hard to educate his fellow countrymen. In a radio address to the nation on May 27, 1941, Roosevelt pledged that the United States would "actively resist wherever necessary, and with all our resources, every attempt by Hitler to extend his Nazi domination to the Western Hemisphere," and would "give every assistance to Britain and to all who are… resisting Hitlerism… with force of arms." America, in other words, had to be ready to defend itself and the rest of the Western Hemisphere. The president challenged Americans to prepare to fight, if necessary. He said, "Your government has the right to expect of all citizens that they take part in the common work of our common defense," and that the future of all free enterprise was at stake.

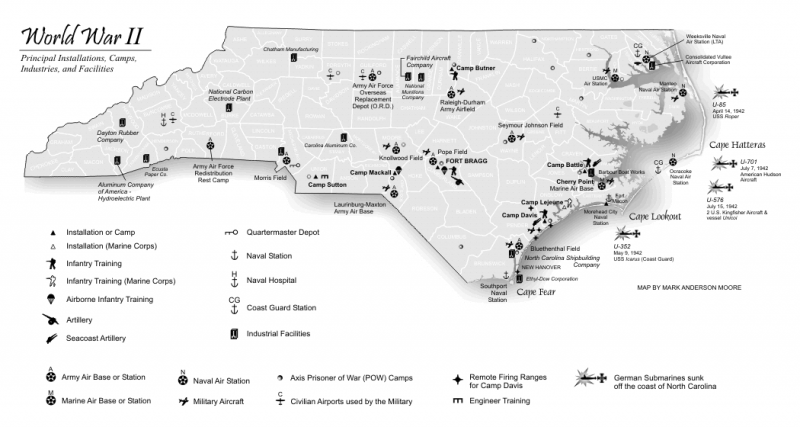

Roosevelt's determination to provide for the national defense in 1940 led to a military buildup around the nation, especially in North Carolina. Military base construction became a major industry in the state during 1940 through 1943, providing important economic and social benefits to Tar Heels from the Coastal Plain to the Mountains. The Great Depression of the 1930s had created a legacy of high unemployment and slow economic growth. By the summer of 1940, though, tens of thousands of North Carolinians had joined construction companies at Fort Bragg, on the outskirts of Fayetteville, and at Camp Davis, near Wilmington. Great feats of engineering and building were under way. In late 1941 work began on large marine corps facilities at Jacksonville and Havelock, swelling the ranks of the employed by more tens of thousands. It was an economic miracle.

North Carolina became one of the leading states contributing to the nation's growing military efforts. Before 1940, Fort Bragg—activated during World War I as an artillery training center—was the only permanent military installation in the state. During World War II, Fort Bragg grew from a post with a few thousand soldiers to a post with over 100,000. Nearby Fayetteville, a town of 17,000 on the eve of the war, soon struggled to find housing for hundreds of families who accompanied soldiers assigned to the post. The same was true in Goldsboro, home of Seymour Johnson Army Airfield; Havelock, site of Cherry Point Marine Corps Air Station, which also impacted New Bern and Morehead City; and Jacksonville, adjacent to Camp Lejeune. Significantly, each of these massive military bases has remained on active and important service into the twenty-first century.

Commenting on the impact of the defense buildup in North Carolina in his inaugural address on January 9, 1941, Governor J. Melville Broughton said that "not since the beginning of our national history has our democracy been so threatened. Acutely conscious of the danger, our nation is girding itself for defense and preservation. The Congress of the United States… in the session of 1940 appropriated for defense the largest sum of money ever before appropriated in a similar length of time by any nation on earth, in peace or war."

The Japanese attack on Hawaii's Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, brought the United States into World War II and sped up military base construction around the state. Work began at Seymour Johnson and Laurinburg-Maxton Army Air Force bases, Camp Butner, Camp Sutton, and many other stations, airfields, and camps. The effect of the signing of construction contracts at each of these bases was magnetic, drawing workers from communities up to a hundred miles away to job sites. Roads became lined with tents, trailers, and various temporary dwellings. Workers arrived each day on foot, by bus or carpool, or in farm trucks. The draw of the military projects included a decent paycheck, job training, and the hope for continued work. In La Grange local businessman Roy Rouse started a bus company to carry workers to job sites at Fort Bragg, some seventy miles distant, and to Cherry Point, more than fifty miles away. Camp Davis construction drew workers from as far away as Harkers Island, Morehead City, Wilmington, Richlands, Warsaw, Wallace, and other communities.

These legions of North Carolinians accomplished spectacular work. Their job was to build—almost from scratch—a network of training bases to support hundreds of thousands of draftees pouring into various branches of the armed services. The U.S. War Department chose southern states like North Carolina for military bases because their climates provided more training days than other parts of the country. Crews built the bases in rural areas or near small towns with few conveniences or comforts. They needed theaters, chapels, recreation centers, hospitals, and post offices. At Fort Bragg, expansion involved thousands of buildings for an infantry division and the Field Artillery Replacement Center. In September 1940 Fort Bragg had 376 assorted buildings, and 5,406 officers and men. By June 1941, it had 3,135 buildings and 67,000 troops.

Life magazine explained in its June 9, 1941, edition that a miracle had taken place at Fort Bragg. At a cost of some $44 million, new roads, sewers, theaters, barracks, chapels, and power lines were constructed. Over 28,000 workers, receiving total wages of $100,000 a day, completed buildings at the rate of one every thirty-two minutes. Sixty-five carloads of building materials arrived daily on the rails of the Cape Fear and Atlantic Coast railroads. At the end of the project, Fort Bragg was the largest military camp in the nation and North Carolina's third-largest community.

Men working on military construction projects or related defense work became eligible to be drafted into the military during 1940. After America entered the war in December 1941, more and more workers were called to service. In some cases women replaced the men, working on new military bases or in defense industries. This was especially true at places like the North Carolina Shipbuilding Company in Wilmington, where women became an important part of the workforce, welding together steel plates, riveting deck plates, and doing other tasks thought of as "men's work."

Across North Carolina in the early 1940s, military base construction provided the infrastructure for training hundreds of thousands of soldiers, marines, and airmen. Fort Bragg and Camp Mackall, which was near Aberdeen, trained thousands of paratroopers and glidermen for great airborne assaults in Europe and the Pacific; Bragg also trained tens of thousands of artillerymen who fought in every theater of war. Camp Sutton, near Monroe, trained army engineers. Camp Butner, north of Durham, was an infantry training center. Camp Lejeune sent thousands of marines to Guadalcanal and other battlefields in the Pacific. Cherry Point prepared pilots for the air war in the Pacific. Seymour Johnson trained bomber crews. Laurinburg-Maxton trained troop transport crews and glider pilots to carry airborne troops to battle. And Greensboro's Army Air Force Basic Training Center (later the Overseas Replacement Depot) provided thousands of trained personnel, turning a southern textile manufacturing center into an "army town." North Carolina became a national defense powerhouse, training more troops during the war years than any other state. More than fifty defense-related bases and camps dotted the state, all with a major and lasting economic impact, although some closed soon after the war.

North Carolina contributed enormous resources and energy to the Allied victory in World War II. The spirit of Tar Heel soldiers can be seen in a letter written by Lieutenant Alexander Smith, of Raleigh. Smith, a member of Company D, Thirtieth Engineers, wrote from Naples, Italy, on October 19, 1943, to Hattie C. Smith: "The Germans are on the run, even though they're proving stubborn, and surely the German soldier can see the fallacy in thinking he can gain anything from fighting. It's a shame we've had to go to so much trouble to show [Adolf] Hitler and [Benito] Mussolini and [Emperor Hideki] Tojo that we won't tolerate their way of life, but now that we've started we won't be satisfied until they learn their lesson well."