Principled Persistence

Are you familiar with the term intersectionality? What types of discrimination did Murray face based on race, gender, and class?

There has been increased attention to Pauli Murray's life in recent years. Scholars recognize Murray's contributions to the civil rights and feminist movements. Gender and sexuality scholars are elevating Murray's status as Queer pioneer as well. There are also intense debates about the best pronouns to use for Pauli Murray in the present. There are some who follow convention and use she/her pronouns. Others use he/his in effort to honor Murray's expressed gender identity distress. This author recognizes this is a delicate issue and raises important questions. The author wishes to avoid misgendering Murray either way. So, this article uses the subject's name as much as possible and they/them/their when not.

Anna Pauline Murray was born in Baltimore, Maryland on November 19, 1910. After their mother's death, they moved to Durham to live with their mother's family. Growing up in Durham, Pauli Murray excelled in school and extracurricular activities. In 1925 they graduated from Durham's Hillside High School at the top of their class. At the time, Hillside was one of Durham's all-Black segregated schools. Despite their achievements, Murray was ineligible to attend their preferred college. Columbia University did not allow women to enroll. After taking extra classes, Murray enrolled in Hunter College in New York City. They graduated with a bachelor's degree in English in 1933. In New York, Murray worked as a school teacher and for the Worker's Progress Administration. Experiences with gender and racial discrimination shaped their future career and politics.

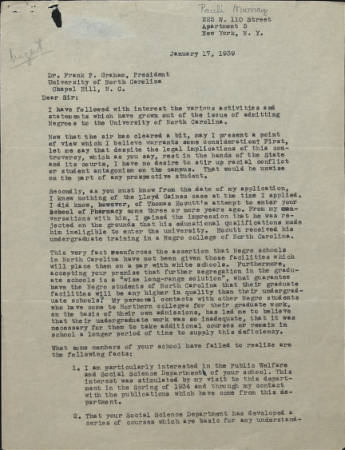

In the late 1930s, Murray became more involved in the Civil Rights Movement. They applied to graduate school at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill in 1938. Although there were a few women on campus, UNC did not accept African Americans. So, UNC denied Murray's application to study sociology. Murray then wrote to UNC Chancellor Frank Porter Graham to plead for admission. Murray described the difficulties in attaining an education in the North. Murray talked about schools requiring extra credits. The letter also mentioned the strain long distance placed on familial relationships. The social and economic costs placed a heavy burden on African American students. Murray acknowledged the difficulties that might come with integration. Yet, Murray believed "this problem can be met through frank, open discussions." The university maintained its position. UNC did not admit its first Black student until 1951.

Pauli Murray's full letter highlights how different forms of discrimination work together. Today, we call this intersectionality. Legal scholar Kimberle Crenshaw coined that term in 1989. Intersectionality describes how different identities like gender, race, or class overlap. Pauli Murray's journey helps us see how gender, race, and class shaped individual opportunities and experiences. Race and gender affected where Murray could go to college. Later gender and class shaped where Murray could go to law school. Likewise, gender influenced how others viewed Murray's legal ideas.

What are some of the ways Pauli Murray influenced the Civil Rights Movement in North Carolina and beyond?

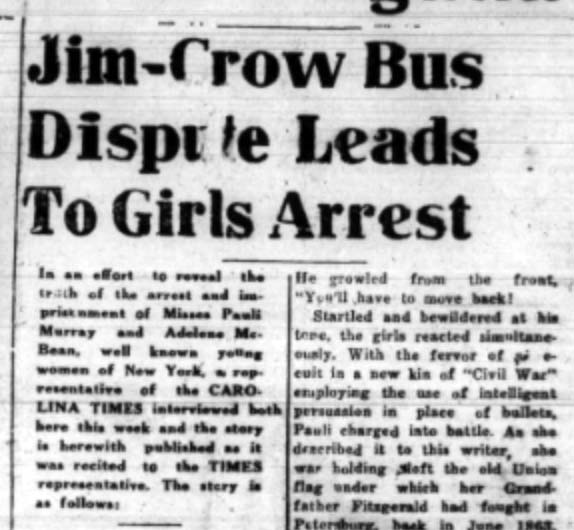

UNC's rejection did not deter Pauli Murray, who remained active in the Civil Rights Movement. Murray influenced the movement by bringing national attention to North Carolina's segregation laws. Their challenge of UNC's admission decision showed that the state's constitution conflicted with the U.S. constitution. Two years later, Murray was on the frontlines again. In 1940 Murray was traveling to Durham to visit family for Easter. Virginia authorities arrested Murray for challenging the law that required segregation on buses. Officials charged and fined Murray for disorderly conduct. Murray returned to New York. There they began fundraising for the Workers Defense League. This work caught the attention of Thurgood Marshall and a Howard Law professor. Leon Ransom was the professor, and he encouraged Murray to apply to Howard Law. Murray did and received a scholarship to attend.

Murray's impact on the national Civil Rights Movement was cemented at Howard. Standing out from her all-male peers, Murray graduated at the top of the class. Murray surprised professors and students and challenged stereotypes. In a final law school paper, Murray argued that racial segregation violated the U.S. Constitution's 13th and 14th amendments. Spottswood Robinson reviewed that paper and returned to it years later. Robinson joined Thurgood Marshall on the N.A.A.C.P's legal team to end Jim Crow. He presented Murray's argument to the rest of the team. The group used Murray's argument to develop their winning strategy in the Brown v. Topeka Board of Education case. In other words, Murray's argument helped topple Jim Crow.

Decades passed before Murray learned about Robinson using that paper. During that time Murray continued to fight for economic, racial, and gender justice. Murray's writings described racial and economic inequality across the United States. After Howard, Murray applied for a legal fellowship at Harvard. The university denied the application because it did not admit women. Murray grew more determined to illustrate the far-reaching impact of gender discrimination. One of Murray's most famous pieces is "Jane Crow and the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title VII." The article was co-written by Mary Eastwood. The authors describe the overlaps between gender and race discrimination. The authors also argue that racial and gender inferiority are based on similar myths. One of those myths is that oppressed groups are content with receiving unequal treatment.

Today, greater attention is expanding Pauli Murray's legacy. More people are learning about Murray's contributions. Murray's life continues to inspire young activists and scholars. In 2017 Yale University named a residential college after Pauli Murray. The University of North Carolina announced a building on its campus will honor Murray as well. That building houses the history, political science, and sociology programs. It has been 70 years since segregation prevented Murray's attendance. Any students who do so now or in the future will have to know the name Pauli Murray.

Concluding questions:

- How can you and your peers help share information about Pauli Murray?

- If you could talk to Pauli Murray today, what advice would you ask about making social justice movements more inclusive?

References:

Cooper, Brittney. "Black, queer, feminist, erased from history: Meet the most important legal scholar you've likely never heard of." Salon. February 18, 2015. Accessed December 10, 2019.

Hine, Darlene Clark, ed. Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005). P. 405-407

Gilmore, Glenda. Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919-1950 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008.

"Folder 521: Pauli Murray to Frank Porter Graham January 17, 1939," in Office of President of the University of North Carolina (System): Frank Porter Graham Records #40007, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Murray, Pauli, and Mary O. Eastwood. "Jane Crow and the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title Vii" George Washington Law Review 34, no. 2 (1965): 232-56

Murray, Pauli. Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage. New York: Harper & Row, 1987.

Schulz, Kathryn. "The Many Lives of Pauli Murray." The New Yorker. April 10, 2017. Accessed December 10, 2019.

"Teaching at the Intersections," Teaching Tolerance, https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/summer-2016/teaching-at-the-.... Accessed July 23, 2020.

Pauli Murray 1976 Interview. https://www.paulimurraycenter.com/paulis-writing

The 1939 Correspondence Between Pauli Murray and Frank Porter Graham

The 1939 Correspondence Between Pauli Murray and Frank Porter Graham