The following is excerpted from the diary of Willard Newton and was published in the Charlotte Observer. Newton was an American soldier fighting in Europe and was one of many referred to as a "doughboy." Doughboy was a common nickname for American soldiers and his diary provides a look into the daily life of an American soldier in Europe during World War I.

July 24, 1918

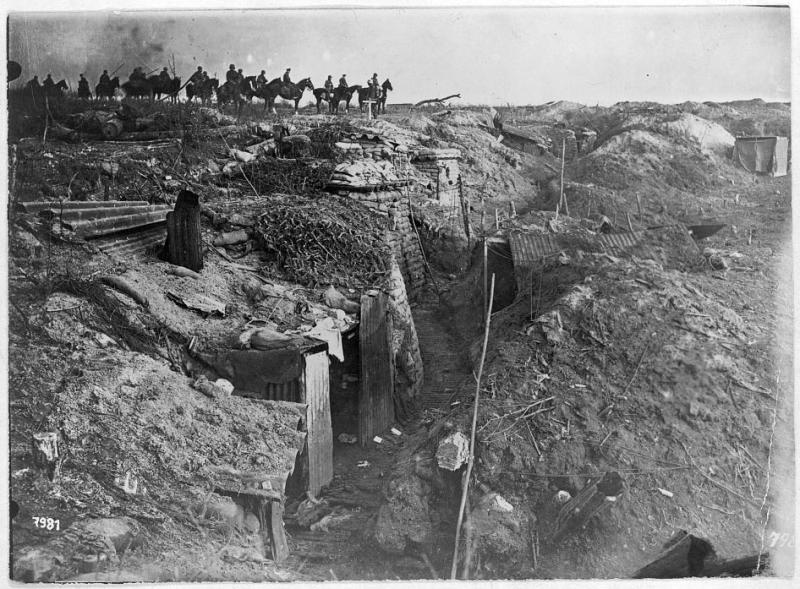

I am glad when day breaks for FritzFritz was a common German name, and was used by Americans to refer to German troops. quits shelling. We are on guard all the morning, being relieved in the afternoon by men from the first battalion, who are moving in and taking our billets. We leave these billets late in the afternoon and move a few kilometers nearer the lines (where friend and foe face each other all the time) and are billeted in small dug-outs, 12 men being assigned to each. The dug-outs having iron frames covered with sheet iron, the sheet iron being covered with dirt and camouflaged with dead bushes.

To kill or to wound any one [sic] a shell must hit directly on one of these dug-outs as they are under the level of the ground. Batteries of artillery, heavy and light, are stationed all around us, some of them firing all the time. Like the dug-outs they are concealed to keep them hid from view of enemy 'planes that come over any chance they get. The third and second platoons are stationed a few hundred yards from us, the third being assigned to billets, while the second platoon has to "dig in" (each man had to dig a hole in the ground large and deep enough to lay his body in) and put up their "pup" tents. The first platoon returns to Proven and camps in an old pasture.

July 25, 1918

A section of the fourth platoon goes up to within a few hundred yards of the front line trenches and spends the morning putting up barbed wire entanglements. The rest of the platoon goes up at night and works in the trenches where the infantry is, repairing damage recently done by German shells. I do not go on either one of these details, but remain in all day. I go over to where there are some Scotch soldiers, known as the Highlanders and talk awhile with them. They are stationed only a short distance from us in tin billets. The Highlander always wears a kilt, whether in battle or on leave. I receive two letters in the afternoon from the States. The guns continue their regular firing on the German lines.

July 26, 1918

The platoon sergeant puts me on the kitchen police for the day. The section work at their same jobs in and near the trenches. The sergeant in charge of our dug-out receives a roll of Charlotte papers from the States and they are eagerly ready by all, especially the Charlotte boys. About 11 p. m., Fritz begins shelling the light railway that is only a few hundred yards to our rear. Some of the shells burst pretty close to our dug-outs, but Fritz hasn't got our numbers yet. After he ceases firing the British artillery opens up and fires the rest of the night.

July 27, 1918

I go up with the section of the platoon that is putting up barbed wire entanglements. We start for the job at 5 a. m., riding nearly five kilometers5 kilometres is about 3 miles. on a light railway train. We are suppose to work until 11:45 a. m., but Fritz starts shelling a battery of guns stationed in and near the field where we are working at 10 a.m., and we leave the field and take shelter in an old shell-wrecked chateaux. We remain here until stopping time and then start back to our billets. We are all wet and muddy from falling on the west ground and jumping in shell holes when the shells fell close, to keep from being hit by pieces of shells. Reaching camp we are excused for the remainder of the day.

July 28, 1918

We get up at 4 a. m. and get ready for our day's work. After eating breakfast we march to Toronto Junction, the place we get on the light railway train, and get our morning train for the chateaux. We ride to within 200 yards of this building and get off but instead of going to our old job we march past it and cut across a large field to another railroad track which we follow for several hundred yards, finally going into a sunken bottom. I soon notice fellows asleep in holes dug back into the bank, while others are on guard. We are hailed, at a small bridge that crosses over the branch that runs through the sunken bottom by a sentinel, who says that only one man must pass over at the time and that he must stoop over as he crosses to keep from being seen by the Germans. Crossing we follow a trench that leads into another trench that is filled with English and doughboys from our own division, most of them laying under the ground in holes they have dug asleep. We come to another low place in the trench and again we have to stoop when crossing. Continuing on up the same trench we come to where the other section of the platoon is working and we begin working with them, throwing mud out of the trenches and putting in duck-boards for the doughboys to walk on. Anxious to say I have seen No Man's Land, I step on a firing base and take a look. Borrowing a pair of field glasses from an English sentinel I look over at the German trenches. Not a human being can be seen though as the Fritzies do not dare to peep over the top. Scores of British 'planes fly about over No Man's Land observing and occasionally diving on the German trenches pouring hundreds of machine gun bullets into them and rising again while the Germans use machine and anti-aircraft guns in an effort to shoot them down. The lieutenant warns us against looking upward while the Germans are shelling the British planes as there is danger of getting hit in the face and eyes by pieces of falling shrapnel. But the fellows seem to pay no attention to his warning, for every time a 'plane would draw fire they would look up at it. We do not work from 1 to 4 p. m., but are instead given that time as a rest period. We stop work for the day at 8 p. m. and start for camp. We stop at the ammunition dump where the train is supposed to meet us, and here we wait for 75 minutes, but no train shows up. In the meantime Fritz has started to shelling the roads and gradually begins shelling near this dump. Our lieutenant seeing that pretty soon Fritz will be shelling the dump gets his platoon started down the road. He was not any too soon in doing this for after we got a few hundred yards down the road shells began falling by twos and fours around this dump. We hike to camp, following the dirt road a while and then the rail track. We made a record hike, reaching camp at 11:30 p. m., sooner than we had expected to. We were all tired and hungry from the day's work and the hike, but our cook was on the job and had a hot supper prepared for us. We did not take time to wash or put our rifles in our dugouts, but threw our rifles on the ground and lined up for "chow." Each man received a mess kit full of mashed pototoes, beef steak and gravy, and hot cup of real coffee. Every one received a plenty and the cook was the talk of the platoon after supper.

Doughboys and the Birth of the Modern American Army

Doughboys and the Birth of the Modern American Army