Bondspeople [people who were enslaved] lived with the constant fear of being sold away from their loved ones by their enslavers, with no chance of reunion. Historians estimate that most bondspeople were sold at least once in their lives. Forced separation from their families was one of many traumas that enslaved individuals had to endure from their enslavers. People sometimes fled when they heard of an impending sale.

To meet the growing demands for sugar and cotton, enslavers developed an active domestic trade of enslaved people to move them to the Deep South. New Orleans, Louisiana, became the largest mart for enslaved people, followed by Richmond, Virginia; Natchez, Mississippi; and Charleston, South Carolina. Between 1820 and 1860, more than 60 percent of the Upper South's enslaved population was "sold South." Covering 25 to 30 miles a day on foot, men, women, and children were marched south by their enslavers in large groups called coffles. Former bondsman Charles Ball remembered that traders of enslaved people bound the women together with rope. They fastened the men first with chains around their necks and then handcuffed them in pairs. The traders removed the restraints when the coffle neared the market.

Johann David Schoepf was born in 1752 in Bayreuth in Germany. He was educated as a physician and scientist, and he came to America during the Revolution, in 1777, as the chief surgeon for German troops in the service of George III. After the war, he traveled throughout the new United States, and when he returned to Europe in 1784 he wrote the book from which this excerpt is taken. Schoepf died in 1800 while serving as president of the United Medical Colleges of Ansbach and Bayreuth.

The day after our arrival we attended a public auction held in front of the Court-house. House-leases for a year were offered for saleA year's rent for houses., and very indifferent houses in the market street, because advantageously placed for trade, were let for 60, 100, and 150 Pd. annual rent.

After this, negroes were letrented or hired out. for 12 months to the highest bidder, by public cry as well. A whole family, man, wife, and 3 children, were hired out at 70 Pd.Pd. stands for the British Pounds. Pounds were used in the United States through the Revolution and into the early Republic because of the instability of the U.S. currency and financial system. Britain and its colonies formed the largest trading market in the world, and so pounds were the common currency in Atlantic trade, and Schoepf's European readers would have understood the value of the pound. a year; and others singly, at 25, 30, 35 Pd., according to age, strength, capability, and usefulness. In North Carolina it is reckoned in the average that a negro should bring his master about 30 Pd. Current a year (180 fl. RhenishFlorins, here abbreviated fl., were coins used in central Europe. Rhenish refers to the region along the Rhine River in Germany. So "fl. Rhenish" is Rhenish florins, a German unit of currency.). In the West IndiesThe islands of the Caribbean. These islands were called the West Indies because when Columbus reached them, he thought he had arrived in Asia and "the Indies." the clear profit which the labor of a negro brings his master, is estimated at 25-30 wordA Guinea was a gold coin minted in the United Kingdom until 1811. It was worth a little more than 1 pound., and in Virginia, according to the nature of the land, at 10-12-15 guineas a year. The keep of a negro here does not come to a great figure, since the daily ration is but a quart of maize, and rarely a little meat or salted fish. Only those negroes kept for house-service are better cared for. Well-disposed masters clothe their negroes once a year, and give them a suit of coarse woollen cloth, two rough shirts, and a pair of shoes. But they who have the largest droves keep them the worst, let them run naked mostly or in rags, and accustom them as much as possible to hunger, but exact of them steady work. Whoever hires a negro, gives on the spot a bond for the amountA bond was a legal contract requiring one person to pay another a certain amount of money. The person who hired the slave would be able to use the money he made using the slave labor to pay the debt to the slave's master. If the slave died, got sick, or ran away, the man was still required to pay the master the agreed-upon amount. As a result, it was risky to "let" a slave, and a man might lose money., to be paid at the end of the term, even should the hired negro fall sick or run off in the meantime. The hirer must also pay the negro's head-taxA head-tax was a tax paid per "head" or per person. Free men paid a head tax, and slaveholders paid a tax on their slaves as well., feed him and clothe him. Hence a negro is capital, put out at a very high interest, but because of elopement and death certainly very unstable.

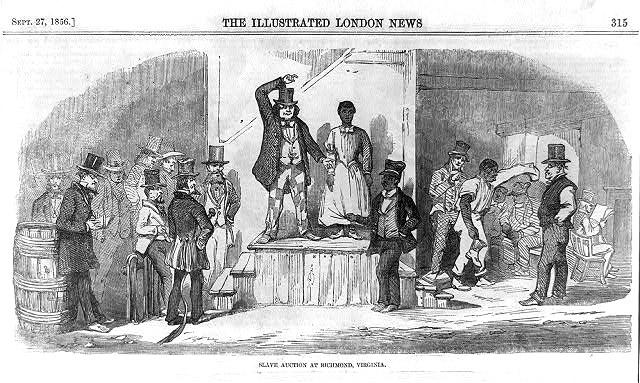

Other negroes were sold and at divers prices, from 120 to 160 and 180 Pd., and thus at 4-5 to 6 times the average annual hire. Their value is determined by age, health, and capacity. A cooperA cooper was a craftsman who built wooden buckets, crates, and barrels. Some masters allowed slaves to learn a trade because they could be hired out and bring in extra income to the master. Sometimes the master would allow the slave to keep a very small fraction of his wages, because the slave was more likely to work harder and earn more money if he thought he might be able to buy his freedom at some point. Since the slave kept only kept a percentage of what he made, the master stood to make a lot of money from an industrious slave. It was very rare for anyone to actually save up enough money to buy their freedom, and masters did not always keep their word in these arrangements., indispensable in pitch and tar making, cost his purchaser 250 Pd., and his 15-year old boy, bred to the same work, fetched 150 Pd. The father was put up first; his anxiety lest his son fall to another purchaser and be separated from him was more painful than his fear of getting into the hands of a hard master. "Who buys me," he was continually calling out, "must buy my son too," and it happened as he desired, for his purchaser, if not from motives of humanity and pity, was for his own advantage obliged so to doSome slave masters tried to keep families together not because they were virtuous, but because a slave who was separated from his or her family was more likely to run away. If a man or woman had children or a spouse on the plantation, he or she was more likely to stay and work for the master. Most runaways were men who had no children or wives. It was much more difficult for women to run away once they had children.. An elderly man and his wife were let go at 200 Pd. But these poor creatures are not always so fortunate; often the husband is snatched from his wife, the children from their mother, if this better answers the purpose of buyer or seller, and no heed is given the doleful prayers with which they seek to prevent a separation.

One cannot without pity and sympathy see these poor creatures exposed on a raised platform, to be carefully examined and felt by buyers. Sorrow and despair are discovered in their look, and they must anxiously expect whether they are to fall to a hard-hearted barbarian or a philanthropist. If negresses are put up, scandalous and indecent questions and jests are permittedEnslaved women were purchased not only for their ability to work, but also for their ability to have children. If a woman was sick or past her child-bearing years, she was worth less to the master. An attractive or strong woman was more desirable at an auction because she would find a husband (although not a legal husband, because slaves could not legally marry) and have children. Any children she had would, of course, belong to her master, and so purchasing a young woman was an investment. Some enslaved women were purchased for sex and kept as mistresses by their masters. A woman's sexual appeal to her master, therefore, could also be a factor in his decision to purchase her.. The auctioneer is at pains to enlarge upon the strength, beauty, health, capacity, faithfulness, and sobriety of his wares, so as to obtain prices so much the higher. On the other hand the negroes auctioned zealously contradict everything good that is said about them; complain of their age, long-standing misery or sickness, and declare that purchasers will be selling themselves in buying them, that they are worth no such high bids: because they know well that the dearer their cost, the more work will be required of them.