The nineteenth century was a time of massive territorial expansion for the United States. The 1803 Louisiana Purchase practically doubled the territory of the United States, which was expanded again after the Mexican American war ended in 1848. With each expansion, however, the question over whether slavery would be permitted in the new territories rose again and again.

By the 1850s, tensions between the north and the south were palpable, in large part due to slavery. On the national stage, these tensions had played out in the Missouri Compromise (1820), the Compromise of 1850, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854). Whether or not slavery would be permitted in new territories seemed a constant tug of war, and the presidential election of 1856 exemplified the struggle between supporters and opponents of the institution. Although the Republican party did not call for the dissolution of the institution of slavery or the freeing of slaves, it did seek to stop slavery from expanding into the western territories -- such as those newly claimed by the nation through the Mexican-American War.

In North Carolina, although 70% of white families held no slaves, openly opposing slavery or openly supporting a candidate who opposed the "southern identity" -- which, to many, included the right to own slaves -- was unlikely to be well-received. One person who spoke out in support of a candidate who opposed the expansion of slavery was Benjamin Hedrick.

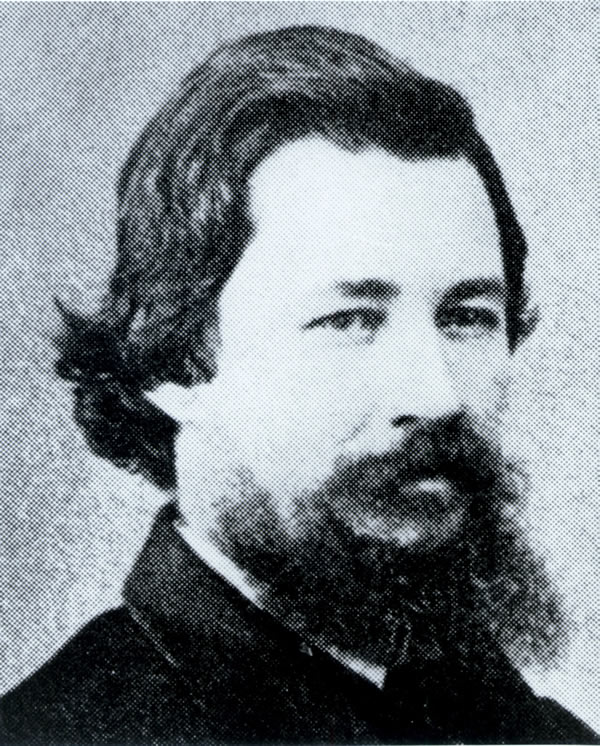

Benjamin Sherwood Hedrick was a chemistry professor at UNC Chapel Hill who voiced his support of the Republican anti-slavery candidate John C. Freémont when several of his students inquired as to who he would vote for in the upcoming (1856) election. Word of Hedrick's support of Frémont spread through the campus and beyond. Two articles were published in the North Carolina Standard -- a conservative Democratic newspaper edited by William Woods Holden, himself a fervent supporter of slavery -- directed at Hedrick. Although Hedrick was not explicitly named in either editorial, it was clear he was the target.

The excerpts below are from the letter written in response to the second editorial admonishing Hedrick. In his letter, Hedrick explains his reasoning for supporting Frémont for president in a way he thinks will be palatable to his fellow North Carolinians. Notice how Hedrick explains supports his stance on slavery, especially who he mentions as "Southern statesmen of the Revolution."

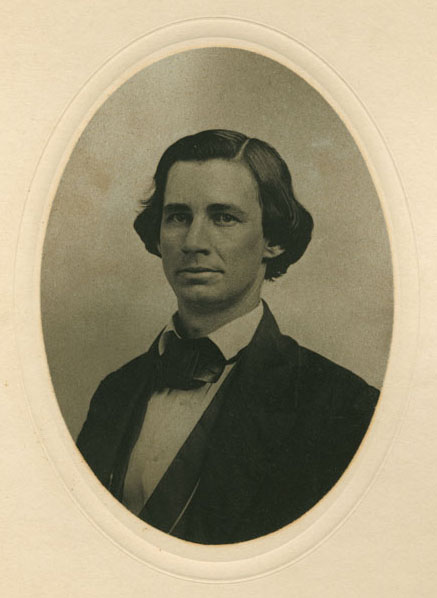

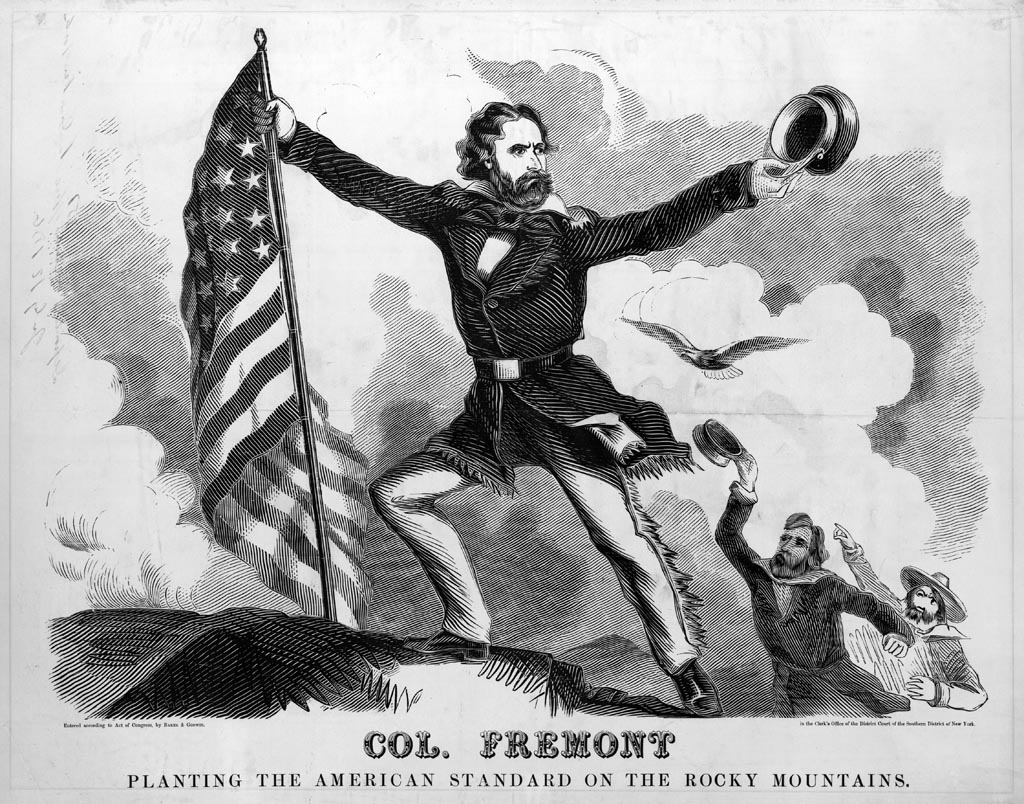

To make the matter short, I say I am in favor of the election of FremontJohn C. Frémont, born in Georgia, was an explorer who fought in the Mexican-American War and became military governor of California. When California became a state in 1850, Frémont was elected as one of its first Senators. In 1856, the Republican Party nominated him as its first candidate for President. to the Presidency; and these are my reasons for my preference:

1st. Because I like the man. He was born and educated at the South. He has lived at the North and the West, and therefore has had an opportunity of becoming acquainted with our whole people, -- an advantage not possessed by his competitorsFrémont's opponents in the 1856 presidential election were James Buchanan, Democrat of Pennsylvania, a former U.S. Representative, Senator, and minister to Great Britain; and former President Millard Fillmore of New York, who ran on the American or "Know-Nothing" Party ticket. Although Frémont was the only major candidate who could claim Southern birth or heritage, he received only 600 votes in the entire South -- and those all from the border states of Delaware and Maryland.. He is known and honored both at home and abroad. He has shown his love of his country by unwavering devotion to its interests....

2d. Because Fremont is on the right side of the great question which now disturbs the public peace. Opposition to slavery extension is neither a Northern or a sectional ismThe term ism was used to refer to any or all of the new and potentially dangerous ideas of the antebellum period -- political views such as abolitionism and socialism, but also new religious ideas such as Mormonism and spiritualism (the belief that the spirits of the dead can be contacted by the living) and pseudo-scientific ideas such as mesmerism (a type of medicine based on a magnetic fluid supposedly existing in humans and other animals). Southerners, especially, referred to northern "isms" as a threat to various forms of social order.. It originated with the great Southern statesmen of the Revolution. Washington, Jefferson, Patrick Henry, Madison, and RandolphEdmund Randolph (1753-1813), a governor of Virginia and U.S. Secretary of State. At the 1787 Constitutional Convention, Randolph moved (successfully) that the word "slavery" be removed from the Constitution. were all opposed to slavery in the abstract, and were all opposed to admitting it into new territory.... Many of these great men were slaveholders; but they did not let self interest blind them to the evils of the system. Jefferson says that slavery exerts an evil influence both upon the whites and the blacks; but he was opposed to the abolition policy, by which the slaves would be turned loose among the whites. In his autobiography he says: "Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate, than that these people are to be free; nor is it less certain that the two races, equally free, can not live in the same government. Nature, habit, opinion have drawn indelible lines between them." Among the evils which he says slavery brings upon the whites, is to make them tyranical and idle. "With the morals of the people their industry also is destroyed. For in a warm climate no man will labor for himself who can make another labor for him. This is so true, that of the proprietors of slaves a very small proportion indeed, are ever seen to labor." What was true in Jefferson's time is true now.... No longer ago than 1850, Henry Clay declared in the Senate -- "I never can, and never will vote, and no earthly power ever will make me vote to spread slavery over territory where it does not exist." At the same time that Clay was opposed to slavery, he was, like Fremont, opposed to the least interference by the general government in the States where it exists. Should there be any interference with subjects belonging to State policy, either by other States or by the federal government, no one will be more ready than myself, to defend the "good old North," my native State. But, with Washington, Jefferson, Franklin, Henry, Randolph, Clay, and WebsterDaniel Webster, long-serving U.S. Senator from Massachusetts, twice Secretary of State, and a staunch opponent of the expansion of slavery. for political teachers, I cannot believe that slavery is preferable to freedom, or that slavery extension is one of the constitutional rights of the South.... [W]hen "Alumnus"Alumnus" was the pseudonym, or pen name, of the author of a letter to the newspaper attacking Hedrick. At this time it was common for people to sign public letters with pseudonyms." talks of "driving me out" for sentiments once held by these great men, I cannot help thinking that he is becoming rather fanatical....

Of my neighbors, friends, and kindred, nearly one-half have left the State since I was old enough to remember. Many is the time I have stood by the loaded emigrant wagon, and given the parting hand to those whose face I was never to look upon again. They were going to seek homes in the free West, knowing, they did, that free and slave labor could not both exist and prosper in the same community. If any one thinks that I speak without knowledge, let him refer to the last census....

It is not, however, my object to attack the institution of slavery. But even the most zealous defender of the patriarchal institution cannot shut his eyes against a few prominent facts. One is, that in nearly all the slave States there is a deficiency of labor. Since the abolition of the African slave trade there is no source for obtaining a supply, except from the natural increaseThe enslaved population of the United States grew because slaves had enough children to more than replace themselves -- it increased "naturally" rather than because more slaves were imported from Africa..... From North Carolina and Virginia nearly the entire increase of the slave population, during the last twenty years, has been sent off to the new States of the SouthwestAt this time the "Southwest" meant Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, and East Texas. What we now think of as the Southwest was newly added to the United States, and conditions there didn't support the sort of large-scale agriculture that made slavery profitable.. In my boyhood I lived on one of the great thoroughfares of travel (near Lock's Bridge on the Yadkin River) and have seen as many as two thousand in a single day, going South, mostly in the hands of speculators. Now the loss of those two thousand did the State a greater injury than would the shipping off of a million of dollars.... I have very little doubt that if the slaves which are now scattered thinly over Tennessee, Kentucky, and Missouri, were back in Virginia and North Carolina, it would be better for all concerned. These old States could then go on and develope the immense wealth which must remain locked up for many years to come. Whilst the new States, free from a system which degrades white labor, would become a land of Common Schools, thrift and industry, equal if not superior to any in the Union. But letting that as it may, still no one can deny that here in North Carolina we need more men, rather than more land. Then why go to war to make more slave States, when we have too much territory already, for the force we have to work it?...

From my knowledge of the people of North Carolina, I believe that the majority of them who will go to Kansas during the next five years, would prefer that it be a free State. I am sure that if I were to go there I should vote to exclude slavery. In doing so I believe that I should advance the best interest of Kansas, and at the same time benefit North Carolina and Virginia, by preventing the carrying away of slaves who may be more profitably employed at home.

Born in the "good old North State," I cherish a love for her and her people that I bear to no other State or people. It will ever be my sincere wish to advance her interests. I also love the Union of the States, secured as it was by the blood and toil of my ancestors; and whatever influence I possess, though small it may be, shall be exerted for its preservation. I do not claim infallibility for my opinions. Wiser and better men have been mistaken. But holding as I do the doctrines once advocated by Washington and Jefferson, I think I should be met by argument and not by denunciation. At any rate, those who prefer to denounce me should at least support their charges by their own name.

B. S. HEDRICK

Chapel Hill, October 1st, 1856.

Primary Source Citation:

Hedrick, Benjamin. "Hedrick's Defense." The North Carolina Standard. October 4, 1856. UNC Libraries. https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/items/show/144 (accessed May 7, 2019)

Additional Resources:

The Benjamin Hedrick Ordeal: A Portait of Antebellum Politics and Debates Over Slavery, a resource created by students and staff of North Carolina State University's History Department.