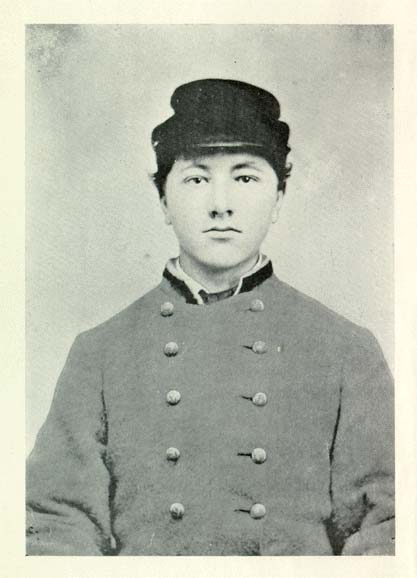

Excerpt from the autobiography of David E. Johnston, who volunteered for the Confederate army in April 1861 at the age of 16.

As a boy, but little more than fifteen years of age, I heard and learned much of the pre-election news, as well as read newspapers, by which I was impressed with the thought that Mr. Lincoln was a very homely, ugly man, was not at all prepossessing, some of the newspapers caricaturing him as the "Illinois Ape," "Vulgar Joker of Small Caliber," and much other of the same kind of silly rubbish was said and published. Some of the negroes inquired if he was sure enough a black man. They had heard him spoken of as a "Black Republican." In the mid 1800s, "black republican" was a pejorative term referring to members of the Republican Party who were sympathetic to the abolitionist movement.

At the election in November, 1860, Mr. Lincoln, the Abolition-Republican candidate, was chosen President, which caused great anxiety and alarm throughout the Southern states - in fact, in other parts of the country. This fear was intensified later by Mr. Lincoln's utterances in his inaugural address, of which more will be said in later chapter.

Late in the Fall of 1860, and in the early Spring of 1861, I was at school on Brush Creek, in the County of Monroe, Virginia... Toward the ending of the school there was much talk about secession and war; in fact, it was the theme of every-day conversation. Even the boys in the school talked learnedly about the questions, and were divided in opinion much in the same proportion as their fathers, guardians and neighbors.

As day after day passed and something new was constantly happening, the feeling and excitement became more intense. As the war clouds began to arise and seemingly to overshadow us, the mutterings of the distant thunder could be heard in the angry words of debate and discussion in the councils of the country, and at home among the extreme advocates of secession on the one hand, and those holding extreme views opposed to the principle and policy of secession on the other. This was not confined to the men alone, but, as before stated, the school boys were would-be statesmen, and in Mr. Bennett's school organized a debating society, in which was most frequently discussed the question, "Shall Virginia Secede from the Union?" -- the question being generally decided in the negative....

When I took part in the discussion it was generally on the affirmative, in favor of secession, my sentiments and convictions leading me in that direction, though as a matter of fact my ideas were very crude, as I knew little of the matter, not having at that time attained my sixteenth year. I had only caught from my uncle, Chapman I. Johnston, who had been educated and trained in the State Rights"States Rights school" refers to those who believed that the power of the federal government was limited to what the Constitution specifically said it could do, and that individual states could refuse to obey federal laws or could secede from the United States. school of politics, some faint ideas of the questions involved in the threatened rupture.

Naturally following my early impressions, I became and was a strong believer in and an advocate of State Rights, and secession, without fair comprehension of what was really meant by the terms. My youthful mind was inspired by the thought that I lived in the South, among a southern people in thought, feeling and sentiment, that their interests were my interests, their assailants and aggressors were equally mine, their country my country, -- a land on which fell the rays of a southern sun, and that the dews which moistened the graves of my ancestors fell from a southern sky; and not only this, but the patriotic songs, and the thought of becoming a soldier, with uniform and bright buttons, marching to the sound of martial music, a journey to Richmond, all animated and enthused me and had the greatest tendency to induce and influence me to become a soldier. Grand anticipations! Fearful reality!

On learning of the adoption of the Ordinance of Secession by the convention, the country was ablaze with the wildest excitement, and preparations for war began in earnest. Volunteer organizations of troops were forming all over the state. Why and wherefore, may be asked. Not to attack the Federal Government, to fight the Northern states, but only to defend Virginia in the event of invasion by a Northern army. There was at this time in the county, already organized and fairly drilled, the volunteer company of Capt. William Eggleston, of New River White Sulphur Springs. Pearisburg and the region roundabout in the most part received the news of the secession of the state with apparent relief and gladness, and immediately James H. French, Esq., of Pearisburg, a lawyer and staunch, bold Southern man in education, sentiment and feeling, assisted by others, commenced the enlistment of a company of volunteer martial infantry to serve for the period of twelve months from the date of being mustered into service, believing that war, if it should come, would not last longer than one year. Enlisting men for war was something new; people are always ready to try something new, and as our people were possessed of a martial spirit, this, together with the excitement and enthusiasm of the occasion, made it no difficult matter to enroll a full company in an incredibly short time. Names were readily obtained, among them my own. I had to go with the boys, -- my neighbors and schoolmates, little thinking, or in the remotest degree anticipating, the terrible hardships and privations which would have to be endured in the four years which followed. The idea then prevalent among our people was that we were not to be absent a great while; that there would probably be no fighting; that Mr. Lincoln was not really in earnest about attempting to coerce the seceded states, and if he was, a few Southern men would suffice to put to rout the hordes of Yankeedom. If, however, the Northern people were intent upon war, our people were ready to meet them, because thoroughly aroused.

Our people had by this time arrived at the conclusion that war was inevitable; no settlement on peaceable and honorable terms could be had. They had therefore left the Union, which seemed to them the only alternative. Consequently we felt obliged to appeal to the sword for the settlement of questions which statesmanship had failed to solve; yet always willing to make a child's bargain with the Northern people, -- "You leave us alone and we will leave you alone." Extravagant utterances and speeches were made as to Southern prowess. It was even said that one Southern man could whip five Yankees; that the old women of the country with corn-cutters could drive a host of Yankees away; but the people who made these assertions knew little of what they were saying, for ere the war had long progressed we found we had our hands full, and it soon became evident that we might like to find someone to help us let go.

Primary Source Citation:

Johnston, David Emmons. The Story of a Confederate Boy in the Civil War. Portland, Or: Glass & Prudhomme Company, 1914.

Published online by Documenting the American South. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/johnstond/menu.html