By the 1850s, nearly all the gold near the surface of North Carolina's gold-mining region had been found and removed. What remained was, according to the author of this article, "found principally in veins of quartz, bedded in the hardest black slate." The article here describes the process of mining that deep gold and the lives and work of the men who mined it.

This article was one of a series in Harper's New Monthly Magazine called "North Carolina Illustrated." The author was David Hunter Strother, who used the pseudonym (pen name) "Porte Crayon." He was a successful illustrator, well-known for his travel writings.

Harper's New Monthly Magazine was first published in 1850, and it quickly grew into a national magazine with a circulation of 50,000. Harper's featured original writing about places and events in the United States. At a time when photographs were still rare and expensive, the magazine's illustrations were a major part of its appeal. During the Civil War, Harper's illustrations and reporting would give many Americans in the North a close look at far-off battlefields.

Article from Harper's Weekly magazine, 1857, tells the story of workers in a North Carolina Gold Mine.

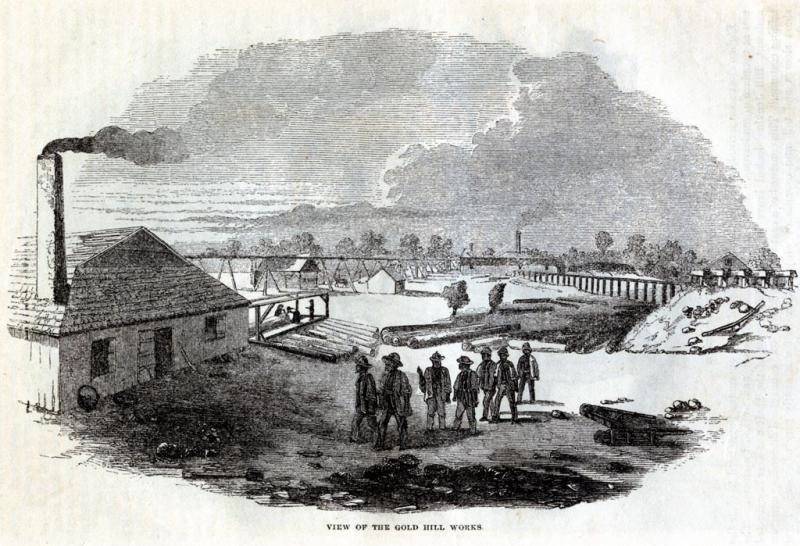

The vehicle that conveyed Porte Crayon and his friend at length reached Gold Hill. This famous village contains about twelve hundred inhabitants, the population being altogether made up of persons interested in and depending on the mines. There is certainly nothing in the appearance of the place or its inhabitants to remind one of its auriferousAuriferous means made from or containing gold. The author is juxtaposing the image of a dirty mining town with the beauty of gold. origin, but, on the contrary, a deal of dirt and shabbiness....

[A tour of the mine]

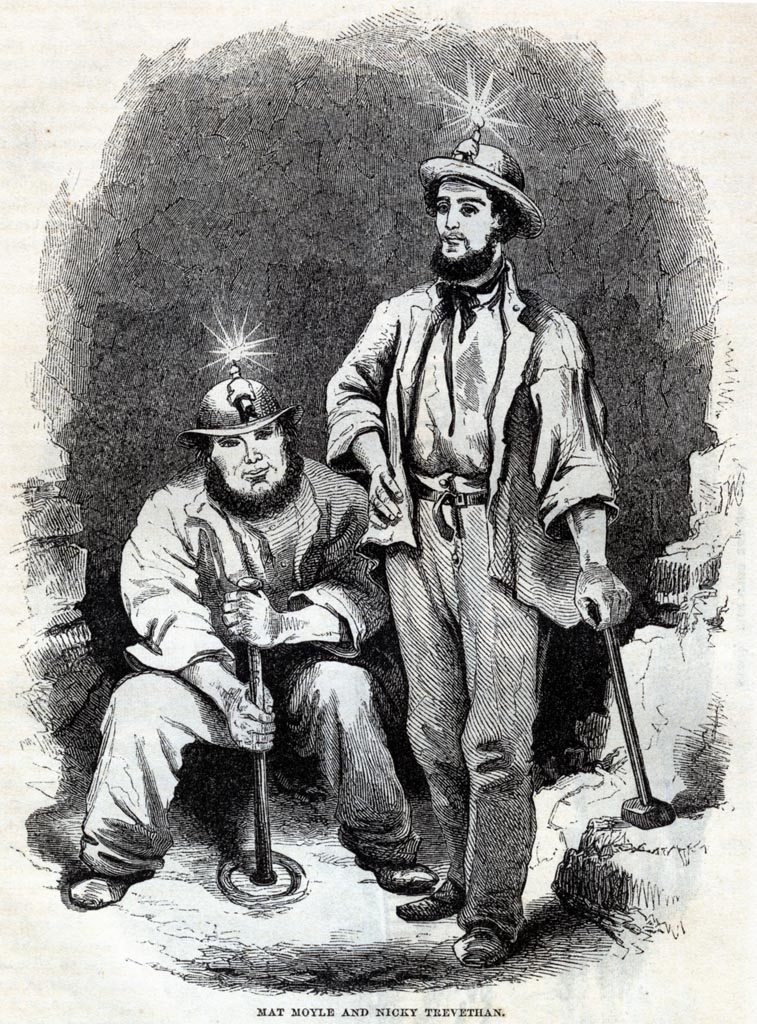

Having presented their credentials to the superintendent of the works, the travelers were politely received, and in due time arrangements were made to enable them to visit the subterraneanSubterranean refers to things below the ground. In literature and in Greek mythology, Subterranean was the underground world full of darkness, caves, and secrets. It was also referred to as the Inferno in the Plato's writings, a Greek philosopher. streets of Gold Hill. The foreman of the working gangs was sent for and our friends placed under his charge, with instructions to show them every thing. Matthew Moyle was a Cornish manCornish people come from Cornwall, a county on the southwestern tip of Britain., a handsome, manly specimen of a Briton. With bluff courtesy he addressed our adventurers:

"You wish to see every thing right, gentlemen?"

"We do."

"Then meet me at the store at eight o'clock this evening, and all things shall be in readiness."

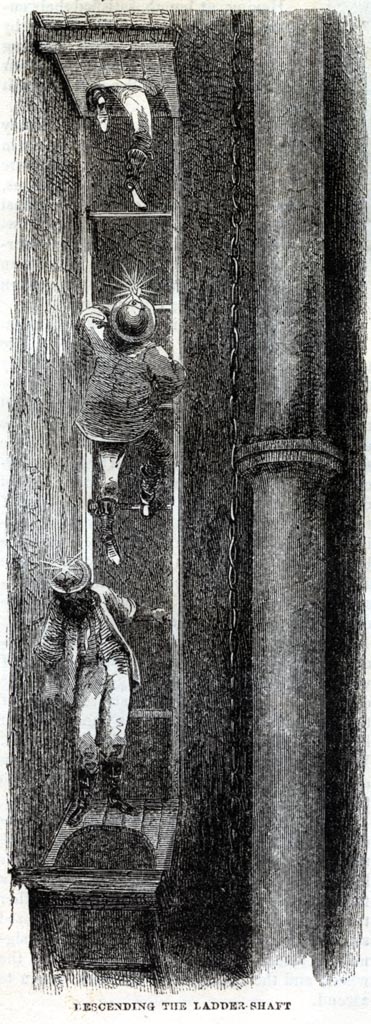

Eight o'clock soon arrived, and all parties were met at the place of rendezvous. Moyle and his assistant, Bill Jenkins, looked brave in their mining costume. This consisted of a coat with short sleeves and tail, and overalls of white duckDuck is a heavy cotton canvas.. A round-topped wide-brimmed hat of indurated felt, protected the head like a helmet. In lieu of crest or plumeCrests and plumes were decorations, such as a feather (plume), worn on hats. each wore a lighted candleThis was decades before electrical lighting was invented, and so the mines would have been very dark. The miners have a candle or wick attached to the front of their hats to help them see in the very dark mines. in front, stuck upon the hat with a wad of clay. Crayon and his companion donned similar suits borrowed for their use, and thus accoutredAccoutred means dressed or equipped, usually in a spectacular fashion. the party proceeded immediately to the mouth of the ladder shaft. This was a square opening lined with heavy timber, and partly occupied by an enormous pump used to clear the mines of waterMany mines were dug deep below the water table -- the level at which water flows underground -- and so the mines often flooded and had to be pumped out. and worked by steam. The "black throat of the shaft was first illuminated by Moyle, who commenced descending a narrow ladder that was nearly perpendicular. Porte Crayon followed next, and then Boston. The ladders were about twenty inches wide, with one side set against the timber lining of the shaft, so that the climber had to manage his elbows to keep from throwing the weight of the body on the other side. Every twenty feet or thereabout the ladders terminated on the platforms of the same width, and barely long enough to enable one to turn about to set foot on the next ladder. In addition, the rounds and platforms were slippery with mud and water. As they reached the bottom of the third or fourth ladder Crayon made a misstep which threw him slightly off his balance, when he felt the iron grasp of the foreman on his arm:

"Steady, man, steady!"

"Thank you, Sir. But, my friend, how much of this road have we to travel?"

"Four hundred and twenty-five feet, Sir, to the bottom of the shaft."

"And those faint blue specks that I see below, so deep deep down that they look like stars reflected in the bosom of a calm lake, what are they?"

"Lights in the miners' hats, who are working below, Sir."

Porte Crayon felt a numbness seize upon his limbs.

"And are we, then, crawling like flies down the sides of this open shaft, with no foothold but these narrow slippery ladders, and nothing between us and the bottom but four hundred feet of unsubstantial darkness?"

"This is the road we miners travel daily," replied the foreman; "you, gentlemen, wished to see all we had to show, and so I chose this route. There is a safer and an easier way if you prefer it."

Crayon looked in the Yankee's face, but there was no flinching there.

"Not at all," replied he; "I was only asking questions to satisfy my curiosity. Lead on until you reach China; we'll follow."

Nevertheless after that did our hero remove his slippery buckskin gloves and grip the muddy rounds with naked hands for better security; and daintily enough he trod those narrow platforms as if he were walking on eggs, and when ever and anon some cheery jest broke out, who knows but it was uttered to scare off an awful consciousness that, returning again and again, would creep numbingly over the senses during the intervals of silence?

But we can not say properly that they ever moved in silence, for the dull sounds that accompanied their downward progress were even worse. The voices of the workmen rose from the depths like inarticulate hollow moanings, and the measured strokes of the mighty pump thumped like the awful pulsations of some earth-born giant.

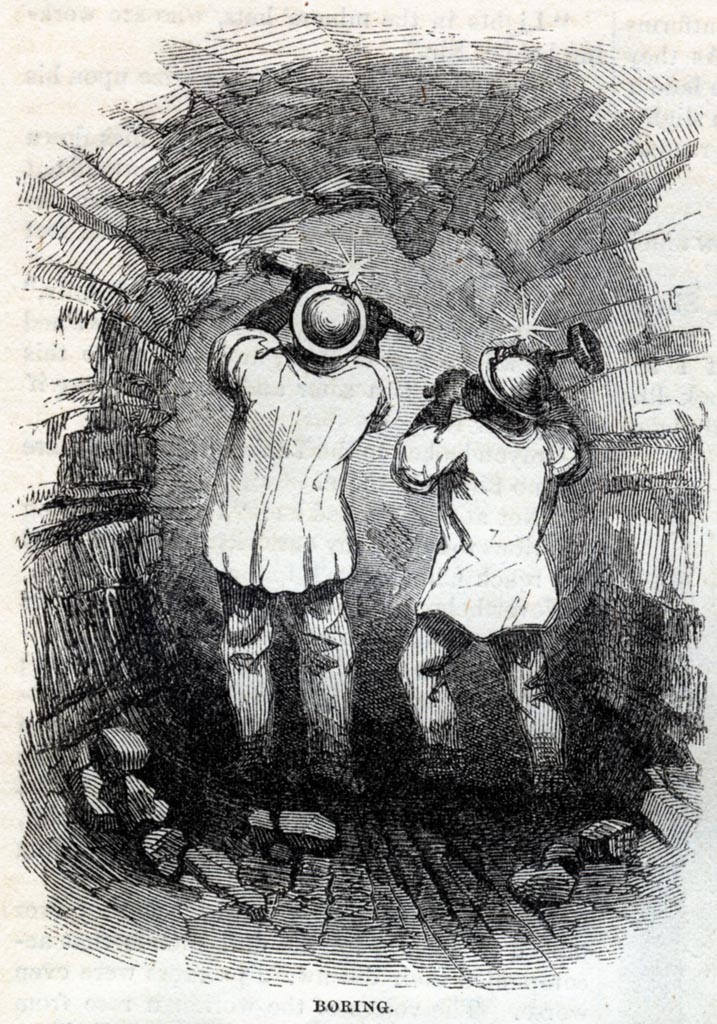

Heated and reeling with fatigue, they at length halted at the two hundred and seventy foot gallery. Here they reposed for a few minutes, and then leaving the shaft walked some distance into the horizontal opening. At the end they found a couple of negroes boring in the rock with iron sledgeA sledge-hammer is very large, about the length of a grown man's arm, with a heavy head on the end. It is commonly used in construction to knock down walls. and augerAn auger is a tool used to drill into the side of the earth. It is long with a screw-driver-like end and a 90 degree handle that a person turns with two hands.. Having satisfied their curiosity here, they returned to the shaft and descended until they reached the three hundred and thirty foot gallery. Here appeared a wild-looking group of miners, twenty or more in number, who had crowded on a narrow gallery of plank that went round the shaft until it seemed ready to break with their weight. A number of negroes were huddled in the entrance of an opposite gallery, and among them our friends preferred to bestow themselves for better security.

The miners were congregated here, awaiting the explosion of a number of blasts in the main gallery. The expectancy was not of long duration, for presently our friends felt and heard a stunning crash as if they had been fired out of a Paixhan gunA Paixhan gun was a type of cannon used on navy ships. It was first invented in France during the 1780s and was a much more accurate and deadly than other types of cannons used on ships., then came another and another in quick succession. They were soon enveloped in an atmosphere of sulphurous smoke, and as the explosions continued Boston remarked, that in a few minutes he should imagine himself in the trenches at SebastopolSebastopol was a seaport in present day Crimea and the site of an important battle during the Crimean war (1853-1856). It was a war for control over trade routes and territory around the Black Sea. In this war, England, France, and the Ottoman Empire (present day Turkey with provinces in the Middle East and Africa) fought against Russia..

When the blasting was over the men returned to their places, and Moyle, having requested his visitors to remain where they were, went to give some directions to the workmen....

When the foreman returned, our friends descended to the bottom of the mine without further stoppages. Here they found a number of men at work, with pick and auger, knocking out the glittering ore. The quartz veins are here seen sparkling on every side with golden sheen. At least so it appears; but the guide dispelled the delusion by informing them that this shining substance was only a sulphuret of copperSulpher (which is yellow when it is in a crystal form) had mixed with copper to make it more golden in color., the gold in the ore being seldom discernible by the naked eye, except in specimens of extraordinary richness. Several of these specimens he found and kindly presented to the visitors.

Having, at length, satisfied their curiosity, and beginning to feel chilled by their long sojourn in these dripping abodes, our friends intimated to their guide that they were disposed to revisit the earth's surface.

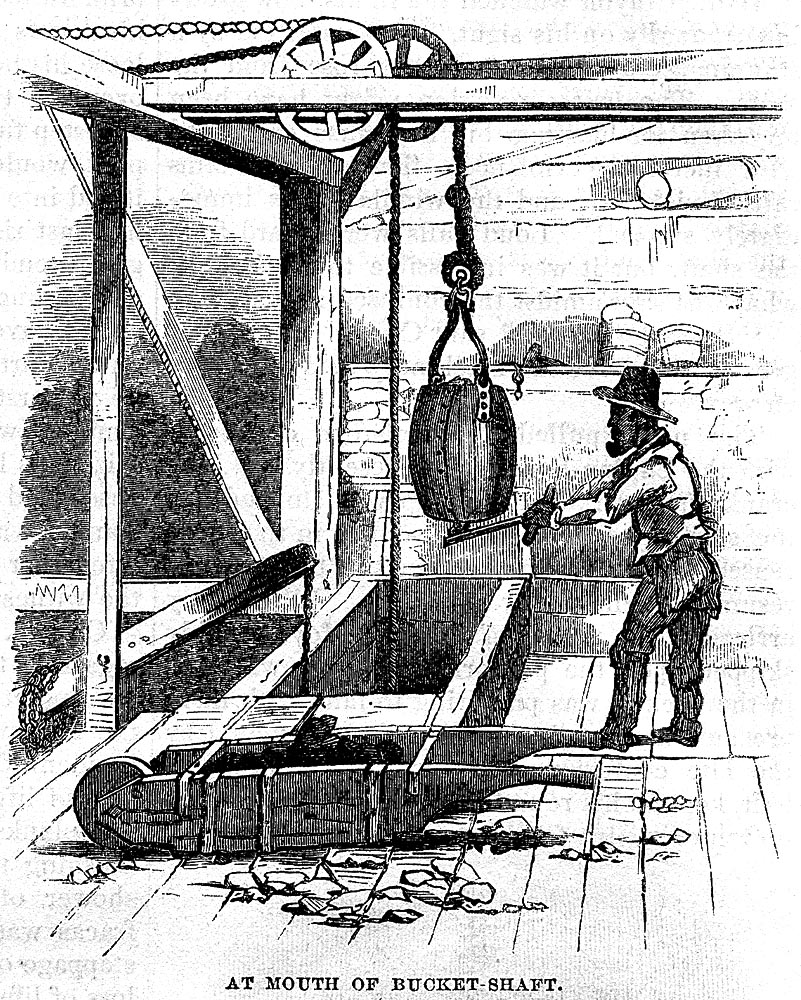

The question then arose whether they should reascend the ladders, or go up in the ore bucket. The ladders were more fatiguing, the bucket more dangerous, and several miners counseled against attempting that mode. Moyle, however, encouraged them with the assurance that they did not lose many men that way. Crayon settled the question by the following observation:

"Sometimes it is prudent to be rash. I'm tired; and, paying due respect to the calves of my legs, I have concluded to try the bucket."

The bucket is a strong copper vessel about the size of a whisky barrel, used to carry the ore to the surface. It is drawn up through the shaft on a strong windlass worked by horse-power. The operation is double—an empty bucket descending as the loaded one ascends. One of the risks from ascending in this way is in passing this bucket. Crayon stuck his legs into the brazen chariot, and held the rope above. Moyle stood gallantly upon the brim, balancing himself lightly with one arm akimbo. The signal-cord was jerked, and up they went.

Slowly and steadily they rose. Crayon talked and laughed, occasionally trusting himself with a glance downward, hugging the rope closer as he looked. Moyle steered clear of the descending bucket, and in a short time our hero found himself at the mouth of the shaft. With much care and a little assistance he was safely landed, and the foreman again descended to bring up the Yankee.

As Moyle went down. Crayon, with due pro-caution, looked down into the shaft to watch the proceeding. He saw the star in the miner's helmet gradually diminish until it became a faint blue speck scarcely visible. Then other tiny stars flitted around, and faint, confused sounds rose from the awful depth. At the signal the attendant at the windlass reversed the wheel, and the bucket, with the men, began to ascend.

While Crayon watched the lights, now growing gradually on his sight, he was startled by a stunning, crashing sound that rose from the shaft. The first concussion might have been mistaken for blasting, but the noise continued with increasing violence. The signal-chains rattled violently, and the windlass was immediately stopped. Loud calls were heard from the shaft, but it was impossible to distinguish what was said amidst the confused roar.

"Stop the pump!" said Crayon to the negro. "I believe the machinery below has given way."

The negro pulled a signal-rope connected with the engine-house, and presently the long crank that worked the pump was stopped; at the same time the frightful sounds in the shaft ceased. The adventurers in the bucket then resumed their upward journey. When they arrived at the mouth of the shaft Moyle nimbly skipped upon the platform. Boston, who was in the bucket, was preparing to land with more precaution; but the horse, probably excited by the late confusion, disregarding the order to halt, kept on his round. The bucket was drawn up ten or twelve feet above the landing, and its brim rested on the windlassA type of winch (a lifting device composed of a rope or chain that is turned or cranked) used to lower buckets into wells or mines, or to lower anchors on a ship.. Boston, to save his hands from being crushed, was obliged to loose his hold on the rope, and throw his arms over the turning beam. One moment more, one step further, and the bucket, with its occupant, would have been whirled over and precipitated into the yawning abyss from which they had just risen. Moyle looked aghast—the negro attendant yelled an oath of mighty power and sprang toward the horse.... Cuffee seized his head and backed him until the bucket descended to the level of the platform, and the Yankee was rescued from his perilous position, altogether less flurried and excited than any of the witnesses.

Crayon then ascertained that his surmise in regard to the hubbub in the shaft was correct. At a point about a hundred and fifty feet from the bottom some of the pump machinery was accidentally diverted from its legitimate business of lifting water, and got to working among the planks and timbers that lined the shaft, crushing through every thing, and sending a shower of boards and splinters below. The fracas was appalling, and, but for the prompt stoppage of the machinery, serious damage and loss of life might have been the result....

Altogether the visit to the mine occupied about four hours, and the travelers were sufficiently fatigued to appreciate their beds that night.

[How the mine works]

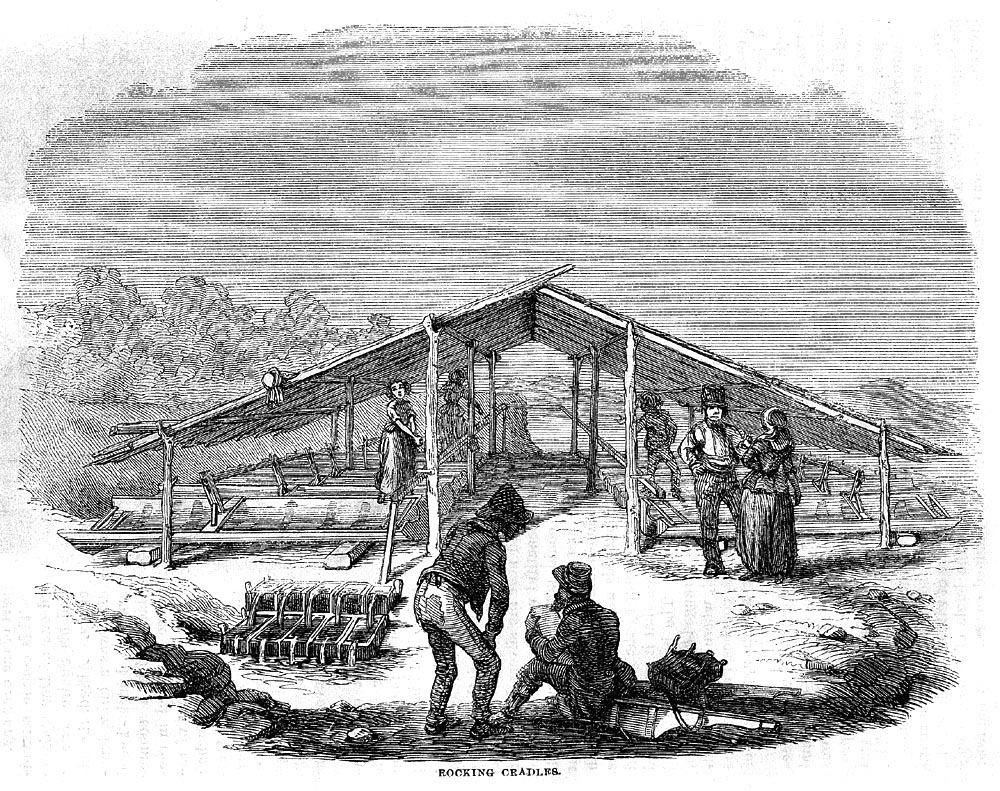

On the following morning they visited the works accompanied by the superintendent, who explained to them in a satisfactory manner the whole process of getting gold. In the first place, the ore taken from the mine is broken with hammers to the size of turnpike stone. It is then subjected to a process of grinding in water, passing through the crushing, dragging, and stirring mills, until it is reduced to an impalpable powder, or, in its wet condition, to a light gray mud, which is washed down, and collects in a large vat below the mills. From this it is carried in wheel-barrows to the cradles. The cradles are eighteen or twenty feet long, formed from the trunks of trees split in twain and scooped out like canoes. They are laid upon parallel timbers with a slight inclination, and fastened together, so that a dozen or more may be moved with the same power. They are closed at the upper end, open at the lower, and at intervals on the inside are cut with shallow grooves to hold the liquid quicksilver. The golden mud is distributed in the upper end of these cradles, a small stream of water turned upon it, and the whole vigorously and continually rocked by machinery. The ground ore is thus carried down by the water, the particles of gold taken up by the quicksilver, and the dross washed out at the lower end, where a blanket is ordinarily kept to prevent the accidental loss of the quicksilver. After each day's performance the quicksilver is taken out, squeezed in a clean blanket or bag, and forms a solid lump called the amalgam. This amalgam is baked in a retort, the quicksilver sublimatesIn chemistry, a substance that sublimes or sublimates changes into a gas when heated, then cools and hardens. Here, the mercury (quicksilver) is boiled off to separate it, and then runs off after it cools back into a liquid. and runs off into another vessel, while the pure gold remains in the retort.

Although this is the most approved mode yet known of separating the gold from the ore, it is so imperfect that, after the great works have washed the dust three or four times over, private enterprise pays for the privilege of washing the refuse, and several persons make a good living at the business. These private establishments are less complicated and far more picturesque in appearance than the great ones. The only machines necessary there are the cradles and the motive power, half a dozen lively little girls from twelve to fifteen years of age. This power, if not so reliable and steady, is far more graceful and entertaining than steam machinery....

Gold Hill, we were informed, belongs to a Northern company. The works are on a more extensive scale than at any other point in North Carolina. They give employment to about three hundred persons, and seem to be in a highly prosperous condition. The working of the mines is chiefly under the direction of Englishmen from the mining districts of Cornwall, and negroes are found to be among the most efficient laborers. All the machinery of the different establishments is worked by steam power except the windlasses for raising the ore, where blind horses are used in preference.