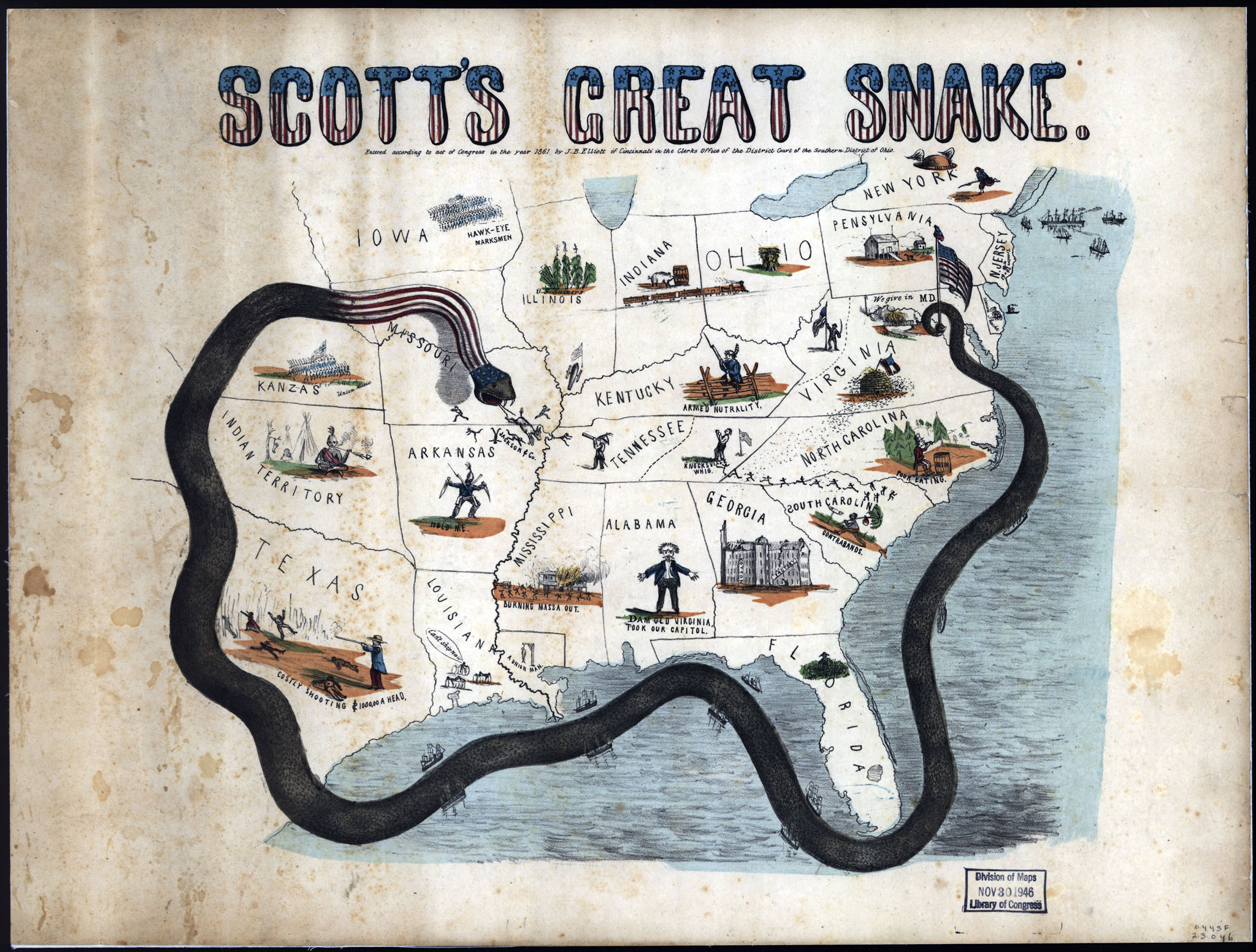

During the Civil War, Union forces established a blockade of Confederate ports designed to prevent the export of cotton and the smuggling of war materiel into the Confederacy. The blockade, although somewhat porous, was an important economic policy that successfully prevented Confederate access to weapons that the industrialized North could produce for itself. The U.S. Government successfully convinced foreign governments to view the blockade as a legitimate tool of war. It was less successful at preventing the smuggling of cotton, weapons, and other materiel from Confederate ports to transfer points in Mexico, the Bahamas, and Cuba, as this trade remained profitable for foreign merchants in those regions and elsewhere.

U.S. Secretary of State William Henry Seward recommended adopting the blockade shortly after the Battle of Fort Sumter in April, 1861 that marked the beginning of Civil War hostilities. Gideon Welles, the Secretary of the Navy, argued for a de facto but undeclared blockade, which would prevent foreign governments from granting the Confederacy belligerent status. President Abraham Lincoln sided with Seward and proclaimed the blockade on April 19. Lincoln extended the blockade to include North Carolina and Virginia on April 27. By July of 1861, the Union Navy had established blockades of all the major southern ports.

South recognized as a belligerent

Following the U.S. announcement of its intention to establish an official blockade of Confederate ports, foreign governments began to recognize the Confederacy as a belligerent When a nation recognized the Confederacy as "belligerent," it established that the Confederate States of America were fighting a legitimate war rather than an illegal rebellion. Foreign governments might not trade or exchange diplomats with rebels, but they would trade with belligerents. Belligerents are also governed by the laws of war, which limited what the U.S. government could do under international law to put down the rebellion. in the Civil War. Great Britain granted belligerent status on May 13, 1861, Spain on June 17, and Brazil on August 1. Other foreign governments issued statements of neutrality.

As the Union Navy took steps to enforce the blockade, controversies arose with foreign governments over the legality of Union seizures of neutral shipping, as well as other related practices. The most important of these was the arrest of Confederate commissioners that precipitated the Trent Affair in November of 1861, an incident that was resolved by the release of the commissioners one month later. Foreign governments acknowledged the right to stop and search neutral ships in international waters, but were displeased by what they saw as violations of the spirit rather than the letter of the law; Union ships typically determined which ships in Caribbean ports were preparing to run the blockade into the Confederacy, and would wait outside the territorial limits for those ships to clear port. British officials were also concerned about the treatment of crews of seized ships, as well as the seizure of British mail. British Minister to the United States, Baron Richard Lyons, repeatedly voiced his government's objections to U.S. Secretary of State William Henry Seward, prompting Seward to invite Lyons to a meeting with President Lincoln. During this meeting Lyons persuaded Lincoln to adopt British neutrality policies by promising that the British Government would continue to view the blockade as a legitimate tool of war.

Effects on international trade

The blockade had a negative impact on the economies of other countries. Textile manufacturing areas in Britain and France that depended on Southern cotton entered periods of high unemployment, while French producers of wine, brandy and silk also suffered when their markets in the Confederacy were cut off. Although Confederate leaders were confident that Southern economic power would compel European powers to intervene in the Civil War on behalf of the Confederacy, Britain and France remained neutral despite their economic problems, and later in the war developed new sources of cotton in Egypt and India. Although British Prime Minister Henry John Temple, Viscount Palmerston, was personally sympathetic to the Confederacy, and many other elite Britons felt similarly, strong domestic abolitionist sentiment in Britain and in his cabinet prevented Palmerston from taking stronger steps toward assisting the Confederacy. Napoleon III of France was also sympathetic to the Confederacy, but wanted to pursue a joint policy with Britain regarding the U.S. Civil War, and so remained neutral. Moreover, Napoleon III's chief concern during the Civil War years was France's intervention in Mexico.

As the war progressed and more territory came under Union control, the blockade became more effective, but less of an international issue. However, until the capture of Fort Fisher in 1865, the Confederate Army was still able to obtain some supplies via blockade running ships.

Source Citation:

"The Blockade of Confederate Ports, 1861-1865." Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs. United States Department of State. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1861-1865/blockade