The women's rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s grew out of the turbulent social upheaval that characterized those decades of American history. This movement is often called "second wave feminism" to differentiate it from the suffrage movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (or "first wave feminism"). Feminists sought to achieve equality for women by challenging unfair labor practices and discriminatory laws. They provided women with educational material about sex and reproduction and fought to legalize all forms of birth control. They established political organizations and wrote books, articles, and essays challenging sexism in society.

But to obtain equality, women needed to change the way society thought of, spoke about, and treated women. This was more than simply changing laws -- this required a fundamental shift in all aspects American society so that women and men would be considered equal. Feminists' chief goal in the the 1960s and 1970s was to overturn the pervasive belief that because women were biologically different from men, they were intellectually inferior, more emotional, and better suited to domestic life than to politics or careers. Women's awareness that they are, and should be, equal was called feminist consciousness.

Equal Pay for Equal Work

One of the most significant events that contributed to the rise of feminist consciousness among American women was the publication of a report by the Presidential Commission on the Status of Women in 1963. Chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt, the commission reassessed women's place in the economy, the family, and the legal system. The commission's final report documented discrimination in employment, unequal pay, lack of social services such as child care, and continuing legal inequality for women. It raised awareness that women's inequality was systemic, not isolated or individual.

President John F. Kennedy responded by ordering federal agencies to hire for career positions "solely on the basis of ability to meet the requirements of the position, and without regard to sex." The same year, Congress passed the Equal Pay Act, which made it illegal to have different rates of pay for women and men who did equal work. For the first time, the federal government restricted discrimination against women by private employers.

Importantly, though, the Equal Pay Act did not require that private businesses give women and men the same consideration for hiring. Employers often refused to hire women for jobs they considered better suited to men. Feminists challenged this practice through court cases and petitions to Congress. In 1968, Congress extended civil rights legislation, which prohibited discrimination in the workplace on the basis of race, to ban gender bias as well.

The Feminine Mystique

Another major work that inspired the Women's Rights Movement was Betty Friedan's book The Feminine Mystique, published in 1963. Friedan defined the "feminine mystique" as the idea that a woman's happiness and identity, indeed what made her complete, required sublimating her own desires and interests to those of her husband and children. By being a selfless wife and mother, a woman would achieve happiness. Friedan came to the realization that this was not true. Women, like men, needed to have an identity that was uniquely their own. They had desires and dreams that could not be met by being a wife and mother because these roles required the woman to stop being "herself." Friedan argued that women should work in professions and that through education and meaningful employment outside of the home, women would regain a sense of self-worth, individuality, and individual accomplishment, denied them in the home. Friedan's book sold nearly three million copies in its first three years in print.

The National Organization for Women

Betty Friedan joined with other women's rights activists in 1966 to form the National Organization for Women. Chapters of NOW were formed in cities and towns all over America. The goal of NOW was to overturn the sexist attitudes prevalent in American society by challenging regressive laws, suing business for discrimination, and educating American men and women about the need for women's equality.

NOW's mission statement said,

We believe that a true partnership between the sexes demands a different concept of marriage, an equitable sharing of the responsibilities of home and children and of the economic burdens of their support. We believe that proper recognition should be given to the economic and social values of homemaking and child care.

NOW's founders promised to "protest and endeavor to change the false image of women now prevalent in the mass media and in the texts, ceremonies, laws and practices of major social institutions… church, state, college, factor or office which in the guise of protectiveness… foster in women self denigration, dependence, and evasion of responsibility, undermine their confidence in their own abilities, and foster contempt for women."

In 1967, the organization added to its Bill of Rights for Women the "right of women to control their own reproductive lives" and set a goal to challenge restrictive abortion laws and expanding access to contraception. In 1967, NOW also included to its agenda paid maternity leave, educational aid, job training, and tax deductions for child care.

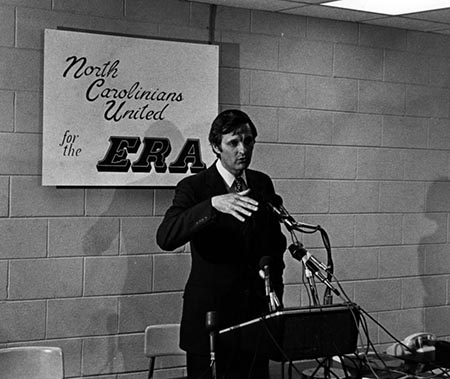

The Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), an amendment to the U.S. Constitution guaranteeing equality for women under the law, was first introduced at a women's rights convention in 1923. The proposed amendment stated simply, "Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction." That same year, the amendment was introduced, and defeated, in Congress.

During World War II, women were asked to do "men's work" in factories to support the war effort, and women's equality again became a political issue. The Republican and Democratic parties added support of the Equal Rights Amendment to their platforms. In 1943, Alice Paul, a suffragist and women's rights activist, rewrote the ERA to read "Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex." This more limited version of the ERA, sometimes called the "Alice Paul amendment," was introduced and defeated in every session of Congress from 1943 until the 1960s.

In the 1960s, women's rights organizations made passage of the Equal Rights Amendment a key goal of the women's movement. By 1972, organized labor and an increasing number of mainstream groups joined the call for the ERA. The Equal Rights Amendment passed the Senate and the House of Representatives, and on March 22, 1972, it was sent to the states for ratification. An amendment requires ratification (approval) by three-quarters of the states to become a part of the U.S. Constitution.The amendment was written to require ratification by the states within seven years; however, that deadline was extended, and the amendment has been introduced into every Congress since the deadline. On May 30, 2018, Illinois became the 37th state to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment, meaning that only one more state must ratify the Equal Rights Amendment for it to become part of the United States Constitution. Even without the federal amendment, many state constitutions now guarantee equal rights for women under the law. (updated August 8, 2018).

Birth Control

Prior to 1873, most forms of birth control were legal in the United States, as was educational material about contraception. Condoms were available, though not widely used. Abortion was legal in many states until the fourth month of pregnancy -- the time of "quickening," when the pregnant women felt the baby move. Before ultrasound technology allowed people to see inside the body, most people believed that life began at quickening. As a result, abortions were widely available. Women could induce abortion by ingesting chemicals or herbs, and midwives and doctors knew how to agitate the uterus in order to expel the fetus.

In 1873, Congress passed the "Comstock laws," which prohibited using the U.S. mail to ship contraceptives or material for sexual education. Abortions were also criminalized. From the 1870s until the 1960s, it was difficult to gain access to birth control of any kind, and a woman could obtain an abortion only if her health was at risk or if she was determined to be mentally ill. Some states made an exception for victims of rape and incest, but in most states abortion was illegal even under these circumstances.

In 1960, the first oral contraceptives were approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but were made available only to married women. Married women responded enthusiastically, and "the pill" quickly became the most popular form of birth control in the United States. For the first time, women had a reliable method of preventing pregnancy that they could control and that no one else need know about. Women could now plan pregnancies around work, schooling, and other life goals, or they could make the decision to never have children at all. In several states where contraceptives of any kind were illegal, though, even married women had difficulty obtaining the pill.

Women's rights activists believed that all women, married or single, needed to be able to control their reproductive lives in order to achieve equality with men. They challenged laws that restricted use of contraceptives to married couples and worked to end state restrictions on contraceptives.

Two important legal cases helped liberalize access to birth control in the United States. In the first, Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), the Supreme Court overturned a doctor's conviction for prescribing contraceptives. The doctor's lawyers argued that married couples had a right to privacy under the Constitution, and the Supreme Court agreed. The court ruled that citizens' right to privacy meant that married persons should be able to practice contraception and that doctors must be permitted to prescribe contraceptives.

The Ninth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution states: "The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people." Although the word privacy does not appear in the Constitution, those other rights have been widely interpreted to include a right to privacy.

In the second case, Massachusetts v. Baird (1972), William Baird appealed his conviction for distributing condoms to unmarried women. The Supreme Court overturned his conviction, ruling that the right of privacy also extended to unmarried women.

In Roe v. Wade (1973), the Supreme Court extended this right to privacy to include abortions. Not only feminist organizations but physicians argued that abortion should be made legal. Even in states where abortion was illegal, women still had them, often in dangerous circumstances that risked their health. Every year thousands of women ended up in emergency rooms from botched abortions, and some women died. The medical community argued that abortions must be supervised by trained medical professionals, and that the only way to ensure this was to legalize the procedure.

In Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court struck down federal and state laws banning abortion. The court argued that its decision did not create a new law, but simply overturned laws that were unconstitutional. "The restrictive criminal abortion laws in effect in a majority of States today," the justices wrote, "are of relatively recent vintage. Those laws, generally proscribing abortion or its attempt at any time during pregnancy except when necessary to preserve the pregnant woman's life, are not of ancient or even of common-law origin. Instead, they derive from statutory changes effected, for the most part, in the latter half of the 19th century."

Divisions in the Feminist Movement

By the 1970s, many different organizations and voices influenced the women's movement. Not all women, for example, agreed with NOW's agenda. Many argued that NOW was too white and middle class to address problems faced by poor women and racial minorities. African-American feminists felt left out of the women's movement because they believed that organizations such as NOW were dominated by white, middle-class women. African-American feminists argued that black women were oppressed not only because of their gender but because of their race. They believed that although black and white feminists had some common goals, African American women needed separate organizations to deal with this dual discrimination.

Others wanted feminism to be more radical. One radical group of feminists was the Redstockings, organized in 1969. In their manifesto, the Redstockings insisted that women were "an oppressed class… exploited as sex objects, breeders, domestic servants, and cheap labor… considered inferior beings whose only purpose is to enhance men's lives... We take the woman's side in everything." Redstockings used blunt anti-male rhetoric: "All men receive economic, sexual, and sociological benefits from male supremacy. All men have oppressed women" and were "male chauvinist pigs."

Some radical feminists called on women "to isolate themselves from men in order to come to terms with what it means to be female." They argued that heterosexual relationships were doomed and that same-sex relationships were the only way for women to have equal partnerships. This, of course, was not the answer that most straight women were looking for, and most feminists thought that there should be a way to be a feminist and still have relationships with men.

Lesbian feminists, by contrast, had become frustrated with mainstream feminists' assumptions that all feminists were straight and were therefore interested in issues of marriage, divorce, child care, and reproduction. NOW was silent about homophobia and discrimination against lesbians.

Ultimately, the message of feminism was expanded to include all ways in which women are oppressed and to recognize that women of different class, race, and sexual orientation are commonly discriminated against because they are first and foremost women.

The 1970s and Beyond

By the early 1980s, most of the major legal battles of the women's rights movement had been won. Women were accepted to colleges on an equal bases with men, it was illegal to discriminate against women in the work place, and women's access to birth control and abortion was protected by the courts. Many women felt that they were living in a post-feminist age, one in which men and women were equals, and they were no longer interested in being active participants in a women's movement.

But activists caution that there is still work to be done. Women are frequently paid less than men for the same work even when they have the same education. Corporate executives and legislators are still overwhelmingly men. Women and single mothers make up a majority of the poor in America. Battles over abortion and access to birth control continue. Feminists also argue that while women have achieved legal equality, there are social and cultural limitations that must be overturned before women achieve full equality.