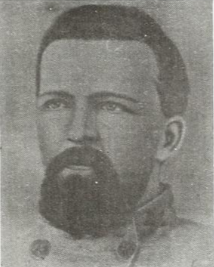

20 Dec. 1828–3 July 1863

Isaac Erwin Avery, Confederate officer, fourth son of Isaac Thomas and Harriet Erwin Avery, was born at Swan Ponds in Burke County. He grew up on the family plantation and entered The University of North Carolina in 1847, but he attended for only one year. He then assisted his father in the operation of the plantation and managed a large farm in Yancey County. The Avery plantation operated with the use of enslaved labor. Isaac Sr. and Jr. routinely created correspondence for the plantation that dealt with the distribution of goods to people they enslaved, as well as purchasing and hiring out of the people they enslaved.

When the Western North Carolina Railroad was chartered in 1854, plans were soon completed to build a road from Salisbury to Morganton and eventually to Asheville. Avery entered into a business relationship with Charles F. Fisher of Salisbury and Samuel McDowell Tate of Morganton, and they contracted to participate in the building of the road. When the eruption of war in 1861 interrupted work on the road, it had been completed to within three miles of Morganton.

Avery undertook to raise a company as soon as his friend Colonel Charles Fisher was appointed by the governor to organize the Sixth North Carolina Regiment of state troops. With the assistance of his brother, A. C. Avery, he enlisted the largest company in the regiment, the enlistees agreeing to serve for three years or the duration of the war. Avery commanded E Company. After a period of training at Company Shops, now Burlington, the regiment was sent to Virginia and placed in the brigade of General Barnard Bee. As a detached regiment, it participated in the Battle of First Manassas and gave a good account of itself in this first great battle of the war. Avery was promoted to lieutenant colonel after the Battle of Seven Pines; and on 18 June 1862, he was promoted to colonel. His regiment participated in all of Lee's great campaigns of the summer and fall of 1862. Avery was seriously wounded at Gaines' Farm in 1862 and was out of action until the fall. After he returned to the regiment, Colonel Robert H. Chilton wrote in an inspection report: "The Sixth North Carolina Regiment, Co. Avery: Arms mixed, but in fine order, although two-thirds of the regiment are badly shod and clad, and 20 barefoot, the regiment shows high character of its officers in its superior neatness, discipline and drill."

As senior colonel, Avery was in command at Gettysburg of what had been known as Hoke's Brigade, composed of the Sixth, Twenty-first, Fifty-fourth and Fifty-seventh North Carolina regiments. On the second day of the battle he was called upon to lead two regiments in an attack on an enemy position on Cemetery Hill. The attack was made, even though one of the two regiments had been detached from Avery's force.

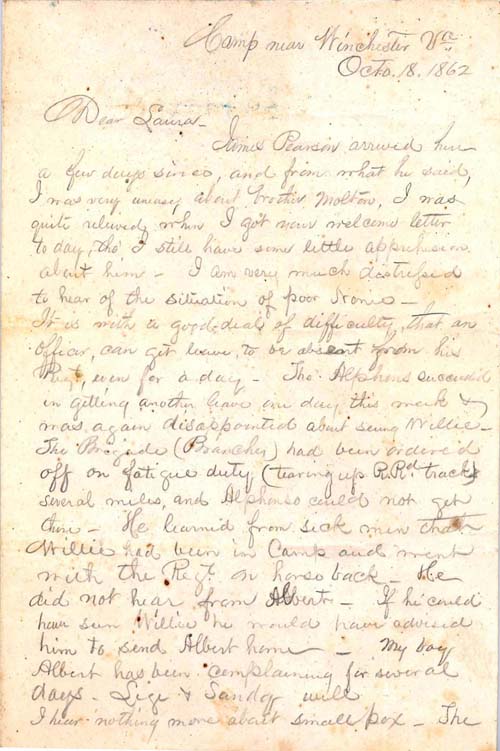

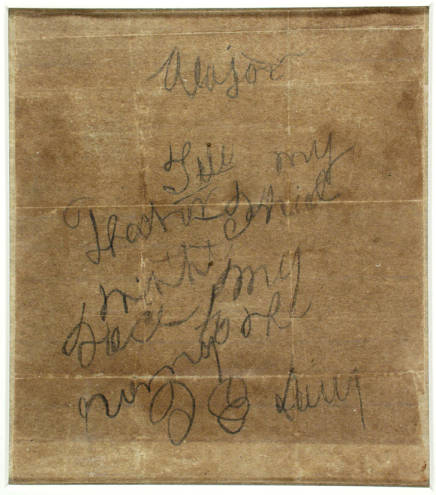

The attack commenced a little before dusk in smoke so thick that the oncoming figures were sometimes obscured. Avery was in front of the brigade on a white horse, the only mounted man of the command. A ball struck him at the base of his neck on the right side and the impact knocked him from the saddle. The missile had found a vital spot. He was stunned by the fall, his right arm went limp, and he began to bleed. His brigade moved on to storm the heights, and to cling there precariously for a time in a desperate hand-to-hand fight but, because no support came, eventually was forced to withdraw. Colonel Avery died there on the field of battle. As he lay among the wounded and dying, he brought out paper and pencil and wrote in uncertain letters, as his aide, Captain J. A. McPherson reported, "Major, tell my father I died with my face to the enemy, I. E. Avery." The original note is now in the State Archives in Raleigh.

The regimental historian of the Fifty-seventh Regiment commented, "the writer supposes that others will write the story of Colonel Avery's military life, or perhaps have done so, but I cannot forbear to say here that he was a gallant soldier, a very efficient brigade commander, and had he lived, would have doubtless risen rapidly in rank." His dying message has been widely noted.

Avery's body was brought by his faithful servant, Elijah Avery, in a cart to Williamsport, where it was buried. Some overzealous Confederates, after the war, had it disinterred and removed to a Confederate cemetery. His friends tried without success to trace the removing party so that his remains might be returned to North Carolina for final burial, but he lies, instead, in an unknown grave.

Colonel Isaac Erwin Avery never married.