12 Nov. 1866–8 Nov. 1950

Ignatius Wadsworth Brock, photographer and painter, was born near Comfort in Jones County, the son of Isaac Brock, a planter, and Harriet Carolina Koonce Brock. He attended the William Rhodes School in Jones County and later Davis and Oak Ridge academies, before studying art at Cooper Union Institute in New York in the early 1890s.

Early ambitions for a career as a landscape artist were sidetracked when Brock turned to photography for what he termed "sketching notes" for future oil paintings. The camera proved a natural medium for his talents, and this ability, coupled with economic necessity, led him to become an apprentice at the Gerock Studio in New Bern, where he worked with the tedious old-fashioned glass plates and developed the darkroom techniques that brought later fame. A few early paintings appeared in art galleries or as reproductions for Victorian magazine covers, and one even went to pay for back rent, but the camera soon replaced the brush as his means of livelihood.

A free spirit with more than a touch of the bohemian, Brock grudgingly settled into the routine of the photographic studio after his marriage in 1897 to Ora Koonce of Jones County. The couple was still honeymooning in the mountains when he decided to settle in Asheville and open his first studio on Biltmore Avenue near the old Swannanoa-Berkely Hotel. Initially he signed his work "Ignatius Brock"; he shortened this designation to "Nace" and eventually settled for "N. Brock," the signature that was best known across the United States and in Europe.

In the first two decades of the twentieth century, Brock's copyrighted pictures of mountain scenery, animals, and children, along with his character studies and an occasional nude, were in heavy demand. Magazines such as Inland Printer made widespread use of his camera work for covers and interior illustration, and he appeared frequently as a teacher and lecturer. He worked primarily with a platinum in tones of black and sepia, and his pictures were priced from one to three dollars.

In 1903 he won the award of the Photographer's Association of Virginia and the Carolinas for best landscape photographs. After three successive wins, ending in 1906, he permanently retired the Slater Trophy of the American Aristotype Company for portraits in nation-wide competition, and he was the winner of Eastman Kodak's Angelo award. He received the $500 first prize offered by the International Photography Association and was a gold medal winner in international competition at Boston, Mass., and Edinburgh, Scotland. Other prizes included the Asheville trophy for the best portrait of a woman and Virginia-Carolinas Association gold medals for best genre photography and best small-size portraits.

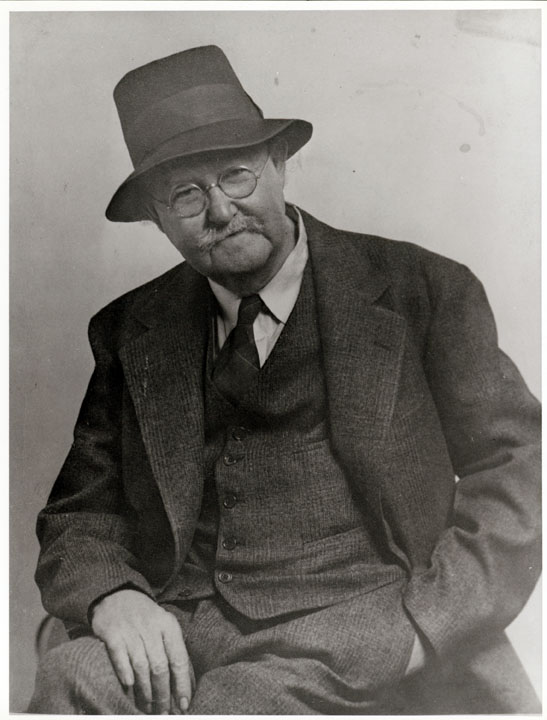

But the little man with the piercing eyes, the tired felt hat, the unruly cowlick, and the straggly mustache cared little for prizes and acclaim. He divided his time among the outdoors, the corner poolroom, and his studio, where he designed special lenses to improve further the quality of his work and experimented with such innovations as blue light. In a never-ending search for perfection, he patiently developed a specially tinted glass plate that provided his darkroom with the pure blue of daylight. The innovation was then taken to a leading light bulb manufacturer with a request for bulbs tinted the identical shade of blue. The company said it was impossible, but within a few years began marketing blue bulbs that were virtual duplicates of the blue light Brock had developed.

Brock the photographer kept abreast and often ahead of the latest developments in his field and added many innovations of his own, but Brock the man refused to bow to conformity. A contemporary recalled him in 1897 as a "dirty, unkempt, unshaven man whose work was his only interest," and more than fifty years later an Asheville newspaperman described him in almost the same terms. "He walked in the pouring rain as though it were sunshine," Doug Reed wrote. "He slept in his clothes and they were sloppy, baggy and greasy most of the time. He would make a bag of peaches a meal. He frequented bars and had a heavy yellow mustache that looked nicotine stained although he never smoked. He once left a socialite seething in his studio while he went across the street for a pool game; but he could set his own time, name his own fee, and make his own rules, and still the people of Asheville shouldered and shoved for nearly half a century for the coveted spot in front of his camera."

Brock operated studios in a variety of locations, all in Asheville, before turning to free-lance portrait painting and the reproduction of miniatures, and in the twilight of his career he worked for E. M. Ball's Plateau Studio. He died in an Asheville nursing home four days short of his eighty-fourth birthday and seven years after his wife, Ora Koonce Brock. The couple were the parents of two daughters, Ora and Carolina, and two sons, Ignatius Wadsworth, Jr., and Isaac.