19 Aug. 1793–27 June 1857

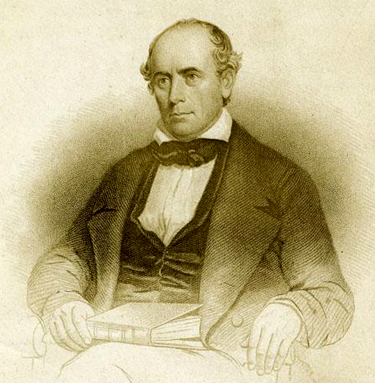

Elisha Mitchell, educator, geologist, Presbyterian minister, and explorer, was born in Washington, Conn., the oldest son of Abner, a farmer, and Phoebe Eliot Mitchell. Abner was a descendant of Matthew Mitchell, who had emigrated from Yorkshire to Massachusetts in 1635 and then moved to Connecticut in 1637. Mitchell's maternal great-grandfather was Jared Eliot, the prominent minister, intellectual, and scientist whose family had also lived in Connecticut since the 1630s. Prepared for college by the Reverend Azel Backus at his school in Bethlehem, Conn., Elisha Mitchell was graduated from Yale University in 1813 in the same class as George E. Badger, Thomas P. Devereux, and Denison Olmsted. At Yale he studied under Professor Benjamin Silliman, who later published a number of Mitchell's scientific articles in the American Journal of Science and Arts, which Silliman edited from 1818 to 1838.

After leaving Yale, Mitchell taught first at Union Hall Academy, conducted by Dr. Lewis E. A. Eigenbrodt in Jamaica, Long Island, and then served as principal of Union Academy in New London, Conn. In 1816 he returned to Yale as a tutor, and the following year he took a brief theological course at Andover, Mass. He was licensed to preach by the Congregationalist Western Association of New Haven County, Conn. Also in 1817 the Reverend Sereno E. Dwight, son of Timothy Dwight of Yale and chaplain of the U.S. Senate, recommended Mitchell for a teaching position in Chapel Hill to William Gaston, then serving both in the U.S. House of Representatives and on the board of trustees of The University of North Carolina.

In January 1818 Mitchell arrived in Chapel Hill to take up his duties as professor of mathematics and natural philosophy. At the same time his former classmate at Yale, Denison Olmsted, was appointed professor of chemistry, geology, and mineralogy. When Olmsted returned to Yale in 1825, Mitchell was chosen to take his place; he taught chemistry, geology, and mineralogy at the university for the next thirty-two years. He also took over and completed the geological survey of North Carolina that Olmsted had begun.

In 1821 Mitchell was ordained by the Presbytery of Orange in Hillsborough; he continued to combine preaching with his education and scientific interests for the remainder of his life. His theological views were clearly expressed in 1825 in a controversy with John Stark Ravenscroft, first bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina, in which Mitchell supported Calvinist doctrine, arguing that Scripture was the only source of religious truth and rejecting the use of tradition as an aid to religious interpretation.

At Chapel Hill, Mitchell's students apparently found him a witty and challenging lecturer and enjoyed his courses. In addition to his teaching, he officiated at chapel services, both on week nights and on Sundays; served as bursar and accountant for the university; and, after 1835, acted in place of President David L. Swain when Swain was away from Chapel Hill. As bursar, Mitchell was in charge of grounds and buildings belonging to the university and worked to increase the variety of flowers, shrubs, and trees on the campus. He also complained that he had more than his share of responsibility for discipline because he lived closer to the college buildings than other members of the faculty. The University of Alabama awarded him an honorary doctor of divinity degree in 1838, and he was a corresponding member of the Boston Society of Natural History.

Mitchell expressed definite opinions on the issues of his day. His journal indicates his distaste for Jacksonian democracy, and in North Carolina he supported the efforts of those who were determined to overcome the Rip Van Winkle image the state had acquired and to promote material progress. In 1834 he urged North Carolinians to support the establishment by the state of a tax-supported system of common schools, not only because he believed that educated citizens were essential to the improvement of society, but also because such schools would provide jobs for women as teachers. Mitchell's interest in the education of women is also evident from the classical education he prescribed for his own daughters.

Having been appointed by Governor William A. Graham to survey a turnpike westward from Raleigh to Buncombe County, Mitchell reported in 1846 that such a turnpike was necessary to encourage trade, increase travel, and connect the eastern and western sections of the state. He also supported the temperance movement and the organization of temperance societies as a means of achieving social progress. His belief in the importance of material improvement was also evident in his descriptions of the mountain regions in western North Carolina, which he visited while working both on the geological survey and on his own research. He deplored the isolation in which mountain people led their lives, which, he argued, led to male laziness, female degradation, and economic stagnation. He looked forward to the day when improved transportation, education, and the development of villages and towns would bring the benefits of civilization to the area.

On the question of slavery, he supported the southern point of view. After coming to Chapel Hill, he acquired slaves himself and, in 1848, preached a sermon arguing that slavery was a system of property holding under God's law and as such was no worse than any other form of property ownership.

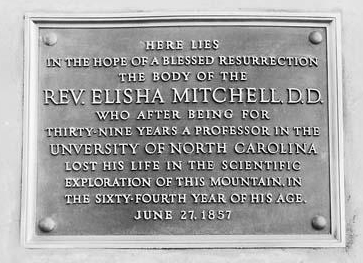

Mitchell is best known for his measurement of the Black Mountain in the Blue Ridge and his claim that one of its peaks was the highest point in the United States east of the Rocky Mountains. He first noted in 1828, in the diary he kept while working on the geological survey, that he believed the Black Mountain to be the highest peak in the area. In 1835 and again in 1838 he measured the mountain, showing the highest peak to be higher than Mount Washington in New Hampshire's White Mountains. In 1844 he returned with improved instruments and measured the highest peak at 6,708 feet, 250 feet higher than Mount Washington. By that time local people were referring to the peak as Mount Mitchell. However, Mitchell's claim was challenged in 1855, when Senator Thomas Clingman, arguing that Mitchell had measured the wrong peak, insisted that the one he had climbed and measured stood at 6,941 feet. As a result of the ensuing controversy, Mitchell returned to the Black Mountain in 1857 in a final attempt to prove Clingman wrong and justify his own previous measurements. On 27 June, leaving his son and guides, he started out alone, was caught in a thunderstorm, and apparently fell down a waterfall and drowned in the pool below.

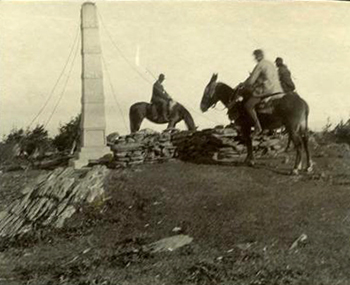

Elisha Mitchell was buried first in Asheville on 10 July 1857. The following year arrangements were made for reburial on top of Mount Mitchell, and on 16 June 1858, with formal ceremonies and addresses by the Right Reverend Bishop James H. Otey of Tennessee and President David L. Swain, Mitchell's remains were buried on the peak. Today his grave is marked by a memorial plaque and observation tower, and the surrounding area has been established as a state park.

In 1881–82 the U.S. Geological Survey upheld Mitchell's measurement of the highest peak on the Black Mountain and officially named it Mount Mitchell. In 1883 the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society was founded in his memory at The University of North Carolina.

On 19 Nov. 1819 Mitchell married Maria Sybil North, of New London, Conn., whom he had met when he was teaching at Union Academy in 1815. They had seven children: Mary Phoebe (m. Richard J. Ashe), Ellen Hannah (m. Dr. Joseph John Summerell), Margaret Eliot, Matthew Henry (died in infancy), Eliza North (m. Richard S. Grant), Charles Andrews, and Henry Eliot (died in infancy).

Photographs are available in the photographic files of the Division of Archives and History, Raleigh, and in the North Carolina Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.