4 July 1828–17 July 1863

James Johnston Pettigrew, lawyer, scholar, and Confederate general, was born at Bonarva in Tyrrell County, eighth of the nine children of Ebenezer and Ann Blount Shepard Pettigrew. He was educated at Bingham's Academy near Hillsborough and entered The University of North Carolina at age fourteen. Highly gifted intellectually, his academic prowess was a tradition at Chapel Hill for many decades. He made a rating of "excellent" in every subject taken in four years and was graduated as valedictorian of the class of 1847.

Pettigrew was a particularly talented mathematician and upon graduation was appointed a professor at the National Observatory by President James K. Polk and Secretary of the Navy John Y. Mason, both alumni of The University of North Carolina. Although esteemed by the head of the observatory, the oceanographer Matthew F. Maury, Pettigrew left after six months to study law. From January 1850 to August 1852 he was in Europe. He studied at the University of Berlin and traveled over most of Western Europe, visiting on foot and on horseback many regions not frequented by tourists. In the course of his travels he acquired a deep romantic identification with the Latin peoples, particularly the Italians and the Spanish. Pettigrew's European study was subsidized by James C. Johnston, of Hayes, his father's friend for whom he had been named. Subsequently, when Pettigrew was thirty, Johnston made him a gift of $50,000 so that he might devote his talents to public service.

On his return from Europe Pettigrew was made a junior law partner of James Louis Petigru at Charleston, S.C. Petigru, Ebenezer Pettigrew's first cousin, was one of the leading attorneys of the country and also the most notable "Union man" of South Carolina. From 1852 to 1861 James Pettigrew was a resident of Charleston. Related through Petigru to many prominent families in the city, he took an active part in the social and public life of the area and was noted for his intellectual pursuits and romantic temperament. Pettigrew was proficient in at least four European languages as well as in Hebrew and Arabic, which he taught himself with the intention of writing a history of the Spanish Moors, whose chivalry and civilizing influence upon Europe he admired. He was said to be an accomplished musician and his mathematical ability was proverbial.

By the time of the Civil War Pettigrew was also an able, self-taught military engineer and artillerist. His chivalric gestures were frequent and unaffected. For example, he resigned as secretary of the U.S. Legation at Madrid when entreated to do so by the wife of a candidate for the office. He visited Cuba intending to take part in an expected revolt on that island. And several times he risked his life to nurse the sick and relieve the poor during epidemics. His subsequent career was a model of modest heroism. Pettigrew never married, although his name was linked by matchmakers to those of several notable South Carolina ladies at various times.

Elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives in 1856, Pettigrew rendered his most notable service in his presentation of a minority report that marshaled the arguments against reopening the foreign slave trade, a measure that had been endorsed by the governor and a legislative committee. (See the Report of the Minority of the Special Committee of Seven, to Whom Was Referred So Much of Governor Adams' Message No. 1 As Relates to Slavery and the Slave Trade, published at Columbia in 1857 and Charleston in 1858.) This paper was reprinted in DeBow's Review, attracted national attention, and together with Pettigrew's role as second in a duel in which a popular young editor was killed, secured his defeat at the next election.

Never an enthusiastic secessionist, Pettigrew had nevertheless become convinced from his association with Massachusetts students in Berlin that a sectional war in America was inevitable. He also believed that the war would be a long, massive, and desperate affair, not the short, decisive campaign that was commonly expected. To prepare himself he took an active part in the South Carolina militia throughout the 1850s. In 1859, when war broke out in Italy against the Austrians, Pettigrew hastened to Europe to fight for the liberty of the Italians and to experience was firsthand. He presented himself to Camillo B. di Cavour as an unpaid volunteer for the front, but hostilities ended before he saw action. He spent some time studying tactics and logistics with French officers, however, and after returning to Charleston was in demand as an instructor for the numerous active militia companies formed there in the months preceding the Civil War. He also published anonymously in Russell's Magazine (vol. 6, March 1860) a satire of the ineffectiveness of the militia together with recommendations for improvement.

As a result of his second trip to Europe he wrote a book entitled Notes on Spain and the Spaniards in the Summer of 1859, With a Glance at Sardinia (1861). Published privately amidst the distraction of Fort Sumter, it attracted little attention at the time but has been praised since by every critic who has read it. Ludwig Lewisohn, for instance, described it as "as interesting a volume of its kind as one can well imagine." The book is at the same time a travel account, an exploration of Spanish history, and a defense of the Spanish against Anglo-Saxon prejudices. It exhibits an intimate knowledge of the life of all classes as well as an attractive style, a capacity for humor, and a profound sympathy for Spanish temperament and traditions. Many of the Spanish characteristics he celebrated—individualism, personal pride, democratic manners, particularism, loyalty, devoutness, disdain for capitalist and utilitarian values—were not irrelevant to what he perceived to be the virtues of the Southern states in contrast to the Northern states, Great Britain, and Germany.

At the secession of South Carolina Pettigrew was appointed chief military aide of Governor Francis W. Pickens and elected colonel of the First Regiment of Rifles. It was Pettigrew who, early in the morning of 27 Dec. 1860, shortly after the Federal forces at Charleston were withdrawn inside Fort Sumter, carried to the Federal commander the governor's demand that the status quo ante be restored. The same day Pettigrew occupied the abandoned Castle Pinckney, and he remained on duty with the forces in Charleston harbor until the surrender of Sumter the next April. Declining several commissions and an invitation to go to Raleigh and electioneer for a high appointment in the North Carolina forces, Pettigrew went to Virginia as a private in the Hampton Legion. Nevertheless, he soon accepted election as colonel of the Twenty-second North Carolina Regiment, organized for regular Confederate service in August 1861. From September 1861 to March 1862 he was stationed on the lower Potomac.

Conspicuous for his ability and energy, Pettigrew was several times recommended for promotion to brigadier general. In a characteristic gesture he repeatedly declined the position, even after an interview with President Jefferson Davis, stating that no one should command a brigade who had not previously led men in action. Then at the beginning of the Peninsula campaign he accepted the commission and became one of the few general officers at that early period who had been neither a U.S. Army officer nor an influential politician. During the Battle of Seven Pines, on 31 May 1862, Pettigrew received a rifle ball through his throat and shoulder while advancing on an enemy position. Refusing to allow men to leave the ranks to carry him to the rear "because from the amount of bleeding I thought the wound to be fatal, [and] it was useless to take men from the field for that purpose," he barely escaped bleeding to death before his wounds were bandaged by a fellow officer. During a Federal counterattack he was shot again in the arm and bayoneted in the leg while he lay on the ground. Reported dead in the Confederacy, Pettigrew was picked up from the field the next morning by Federals, made prisoner, and gradually recuperated from his wounds. When exchanged he was assigned to command a brigade consisting of the Eleventh, Twenty-sixth, Forty-fourth, Forty-seventh, and Fifty-second North Carolina regiments. With these troops Pettigrew fought in a number of small battles in eastern North Carolina between September 1862 and the spring of 1863, including a successful independent action at Blount's Creek on 9 May in which he repulsed a Federal raiding column of superior force. During this period Governor Zebulon B. Vance and the state's members of the Confederate Congress petitioned unsuccessfully for Pettigrew to be assigned command in North Carolina. Highly regarded by both rank and file, Pettigrew deliberately set an example of patriotic sacrifice and cheerful endurance of privation. He lived on privates' fare and allowed himself no leave from duty.

In May 1863 Pettigrew's brigade joined the Army of Northern Virginia for the Pennsylvania campaign. On 1 July, in one of the bloodiest assaults of the war, Pettigrew's brigade drove some of the best Federal units from their position on McPherson's Ridge on the outskirts of Gettysburg. The division commander, Henry Heth, was wounded, and during the next two days of the Battle of Gettysburg Pettigrew commanded his own and three other brigades. On the third day the severely reduced division, under Pettigrew, took part in the dramatic, unsuccessful, and controversial assault known to history as Pickett's Charge. In this attack Pettigrew's horse was hit and he was wounded in the hand; he was said to have been one of the last men to return to the Confederate lines. At Gettysburg Pettigrew's own brigade had the highest casualties of any in the army. During the retreat from Pennsylvania, at the Falling Waters just north of the Potomac early in the morning of 14 July, Pettigrew was shot in the stomach in a melee with a straggling Federal cavalry unit that had ridden into his resting troops by error. Pettigrew refused the immobilization that was the only hope of saving his life, commenting that he had rather die than be captured again. Remaining with the army, he was carried eighteen miles to Bunker Hill, (West) Va., where he died three days later at 6:25 A.M. at age thirty-five.

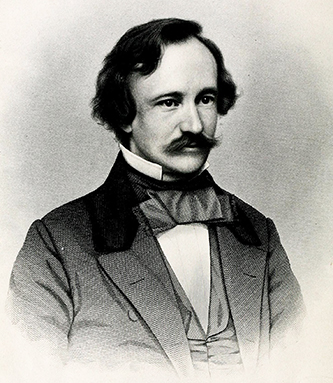

Slender, fair-complexioned, with piercing eyes and a conspicuously high forehead, modest, and ascetic, Pettigrew was dedicated to his society and his duties with a medieval intensity. A portrait in uniform hangs in the Southern Historical Collection at The University of North Carolina, and a prewar likeness appears in James Petigru Carson, Life, Letters, and Speeches of James Louis Petigru (1920). An Episcopalian, actually though not formally devout, Pettigrew was widely read in theology and expressed in his book considerable sympathy for Spanish Catholicism. He was buried at Raleigh on a day of public mourning and after the war was reinterred in the family ground at Bonarva.

Pettigrew's high intellect and chivalric temperament made a deep impression on his contemporaries. Scientist Matthew F. Maury called him "the most promising young man of the South." James Louis Petigru spoke of an intellect greater than John C. Calhoun's. English-born Collett Leventhorpe, who served in Pettigrew's brigade, remarked that he never met a man "who fitted more entirely my 'beau ideal' of the patriot, the soldier, the man of genius, and the accomplished gentleman." The South Carolina scholar William Henry Trescot wrote that Pettigrew alone was evidence that the Southern cause was "not wholly wrong." Cornelia Phillips Spencer said that there were many in North Carolina "who believed he was the good genius of the cause—he was the coming man who should yet guide us to victory." Douglas Southall Freeman wrote that for no officer who served with the Army of Northern Virginia so briefly were there so many praises while living and so many laments when dead. A well-informed student of the Old South, Clement Eaton found that "in no other Southerner did romantic ideals show to greater advantage than in James Johnston Pettigrew."