21 Oct. 1813–13 Mar. 1878

Robert Hardy Smith, lawyer, member of the Provisional Congress of the Confederacy, and a colonel in the Confederate army, was born at Edenton. He was the son of Robert Hardy, Jr. (1780–1841) of Edenton and Elizabeth Gregory Smith (1786–1856) of Hertford, Perquimans County, and the grandson of Joseph of London, England, and Elizabeth Hardy Smith. Both sides of the family supported independence during the American Revolution.

After receiving a strong foundation in classical education, he attended West Point in the fall of 1831. Because of a deficiency in mathematics, he was obliged to leave in January 1832 and found himself on his own because of his father's financial reverses. For a time he taught young students and studied medicine at Norfolk, Va., then moved on to teach on a plantation in his home county, and finally decided to seek his fortune in the Southwest.

In the Alabama counties of Dallas and Sumter he continued to teach and began studying law. In 1835 Smith was admitted to the bar and set up practice in Livingston, Sumter County, where he was associated with William B. Ochiltree (b. Cumberland County, N.C.) and later with Colonel William M. Inge (b. Granville County, N.C.). His considerable gifts as a lawyer soon elevated him to a position of leadership in his profession and in politics. In 1849 he was elected to the lower house of the state legislature and quickly rose to the top ranks of the Whig party. Two years later he reluctantly ran for the state senate but lost by one vote to John A. Winston, a future governor. Returning to his chosen profession, he moved to a challenging and thriving practice at Mobile in 1853. When John A. Campbell, leader of the Mobile bar, was elevated to the U.S. Supreme Court, he selected Smith to take over his firm. During the decade of the 1850s Smith's character and abilities grew, his reputation as a learned lawyer flourished, he practiced his profession before the highest courts in Alabama and Washington, D.C., and he retained an active interest in the politics of his day.

In 1860 he considered himself a Union man, a conservative, and still a Whig by conviction. Smith had opposed the secession movement in Alabama for years and in the national election supported John Bell and Edward Everett. After Abraham Lincoln's election he accepted an appointment by Governor Andrew B. Moore as commissioner to his native state. On 20 Dec. 1860 he addressed the legislature at Raleigh on the subject of cooperation in the event of secession. He reported on his mission to the Alabama Convention at Montgomery and then returned to Mobile to await what he believed to be the coming revolution.

When his state seceded on 11 January, he loyally accepted the decision. Soon afterwards the Alabama convention passed over the avid secessionist William Lowndes Yancey and elected Smith as a delegate-at-large to the Montgomery convention. Alexander H. Stephens of Georgia, vice-president of the Confederacy, believed him to be the most able member of a very capable Alabama delegation. His contributions to the establishment of the Confederate government were significant indeed. The U.S. Constitution and its history were of special interest to Smith and made him a natural choice for membership on the drafting committees of both Confederate constitutions. His voice engendered respect during the convention debates, as did his origination of such reforms as the item veto and his important contribution to the final style and arrangements of the two documents.

The Confederacy had no Federalist Papers and no James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, or John Jay because the exigencies of time insisted that the drafting and ratification process be done quickly. There were many spokesmen for the new permanent constitution, but none spoke with greater insight, perception, or wisdom than did Robert Hardy Smith at Mobile on 30 Mar. 1861. His words were published as An Address to the Citizens of Alabama on the Constitution and Laws of the Confederate States of America.

After concluding his service in the Provisional Congress he returned to Mobile. In 1862 he organized the Thirty-sixth Alabama Infantry and was elected colonel. His unit was assigned to defend the district of the Gulf, which included South Alabama and West Florida. Before the year ended he was forced to resign his commission because of ill health. During the remaining years of the Confederacy he served briefly as president of the district military court, which he caused to be abolished for constitutional reasons. He also reestablished his law practice at Mobile.

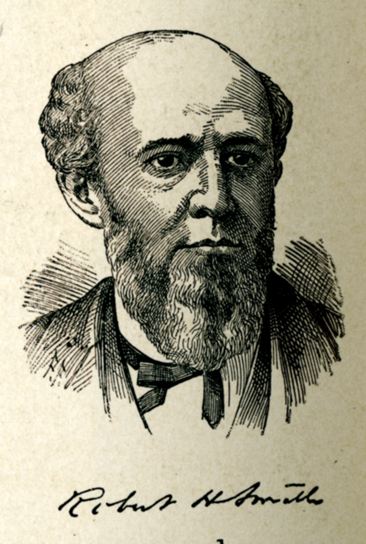

During the postwar period, with his energy restored, his legal career flourished again, and he was engaged in a number of important cases of state and national significance. A portrait of this time preserved the image of a someone who had dedicated his life to the precepts of honor, duty, and virtue. A man of medium stature with slightly rounded shoulders, he had a pleasant face with strikingly deep hazel eyes and an iron gray beard. He died at Mobile. The church of his youth, the Episcopal church, ministered to him during his last days and laid him to rest in Magnolia Cemetery.

Smith was married three times: first, on 12 Jan. 1839, to Evalina Belmont, who died on 4 Dec. 1843; second, on 25 Nov. 1845 to Emily Stuart, who died on 24 Oct. 1846 (both were sisters of Colonel William M. Inge); and third, to Helen Hord, daughter of Thomas Hord Herndon of Greene County, Ala. He was survived by his wife Helen, five sons, and four daughters. Sons Richard Inge, an officer in the Confederate army, Robert Hardy, and Gregory Little were distinguished members of the Mobile bar. Hardy B. Smith, of Mobile, Ala., became the owner of Smith's portrait as a young man and daguerreotype in later life.