See also: Fire Departments; Poultry

On September 3, 1991, a deadly fire started at the Imperial Foods Chicken Processing Plant in Hamlet, North Carolina. Many employees were trapped behind locked doors as flames and smoke filled the building. In the aftermath of the fire, details emerged that indicated ignored safety protocols and improvised equipment repairs led to the preventable blaze and the resulting deaths and injuries. Twenty-five people died in the fire, and fifty-four people were injured. The Hamlet Chicken Processing Fire is regarded as one of the most significant industrial accidents of the twentieth century and led to new worker safety laws in the state.

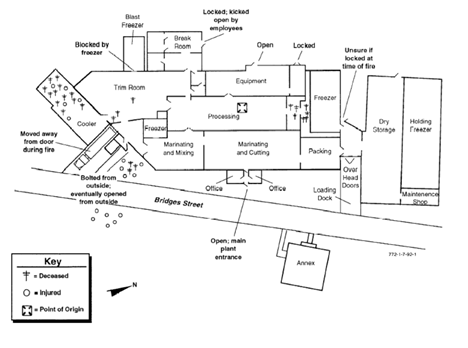

The fire began the morning of Tuesday, September 3, 1991, around 8:00 a.m., after an extended Labor Day weekend. It originated near the center of the plant in the processing area. That morning, hasty and improper repairs were made to a hydraulic line connected to a conveyor belt that carried chicken to the fryers. As a result, the line burst when activated, spraying hydraulic fluid across the factory floor and walls. The oily fluid vaporized and was ignited by the flames of the chicken fryers, which created a rapidly spreading blaze. The burning hydraulic fluid also produced a thick, toxic smoke. The heat from the fire was so intense that the supposedly fire-proof ceiling tiles ignited. The plant’s faulty sprinkler equipment never engaged in response to the fire, which allowed the fire to run rampant.

Employees attempted to flee the rapidly burning building. The location of the fire divided the facility in half. Some employees escaped safely, while others retreated from the flames to adjacent rooms. Several employees attempted to flee through a loading dock door but found it blocked by a delivery truck. Some additional exit doors in the facility were found locked, bolted, or otherwise obstructed. The flames and toxic smoke killed many of the people trapped inside the plant.

Around 8:30 a.m., the Hamlet fire department arrived. Visible smoke billowed from the plant and drew members of the Hamlet community to the scene. Efforts by townspeople, like those who removed a dumpster from a blocked exit with a tractor, and the fire department helped save some of the trapped workers. Neighboring fire departments, including East Rockingham, were called for help. Despite being the closest to the fire, aid from the all-Black brigade of volunteer firefighters of Dobbins Heights was refused. Firefighters from the brigade concluded that this was likely due to racial bias, as help from other, more distant, non-Black departments was accepted.

In the immediate aftermath, firefighters and emergency medical personnel gave aid to those who had managed to escape and identified the bodies of the deceased. Several of the deceased were parents, and the fire left a total of forty-nine children orphaned. That same month, the United States Fire Administration opened an investigation of the fire, the findings from which ultimately revealed regular practices and patterns of corporate negligence.

At the time of the fire, the Imperial Foods Processing Plant was overseen by Brad Roe, the Director of Operations, and his father, Emmett, the company owner. Originally from New York, the Roes were experienced in the chicken processing industry. They initially established Imperial Food Products in Scranton, Pennsylvania in the early 1970s. The Roes moved the plant from Pennsylvania to the South as the cost of production per chicken was much cheaper in the South.

The strict leadership of the Roes was recalled and later documented by Imperial employees. Maintenance workers, like those who repaired the hydraulic line the morning of the fire, reported they were managed by real quick-tempered

bosses and worked as many as seven days a week. The Roes also categorized labor issues like wages and hours raised by Imperial workers as women issues.

Other employees reported that Brad regularly ignored workplace complaints or punished complainants with retaliatory firings.

Investigations opened by the U.S. Fire Administration (a division of the Federal Emergency Management Agency) and the North Carolina Department of Labor (NCDoL) corroborated many of the employees’ testimonies. They found employees at the plant received no formal training related to work responsibilities, nor did they receive workplace safety training. An interview from the NCDoL report stated that Imperial workers were not given any instruction on what to do in the event of a fire or emergency. No fire drills were held and [workers were] not given any instructions on how to use a fire extinguisher.

Both reports also concluded that the ruptured hydraulic line had been improperly repaired at the Roes’s demand and that hasty repairs were a common practice to avoid losses due to down production time. Moreover, accounts from survivors and the plant investigation confirmed that conditions like standing water, locked exits, and faulty equipment were all common at the plant and non-compliant with standards established by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Plant management had no clear or disseminated evacuation plan. Plant managers also fabricated information justifying locked plant doors, dismissed safety codes, and avoided safety inspections mandated by OSHA.

Following the fire, the local community grieved for those who died and organized support for survivors and community members impacted by the fire. Local nonprofits and religious organizations fundraised to help individuals and families displaced and/or injured by the fire. The event was also heavily publicized and was used to advocate for better working conditions. The Hamlet fire also served as a cautionary tale about the desperation of impoverished workers in most of the rural South. Many of Imperial’s employees were willing to work for low pay and dangerous conditions due to limited job opportunities in rural Hamlet.

One person who advocated for change and community support following the fire was Reverend Jesse Jackson. Jackson communicated with those affected by the fire and their families. He prayed with them at hospitals and began advocating for them publicly. In a speech delivered at the burned Imperial Foods Plant, Jackson stated, Never again must workers be trapped behind locked doors! These people would not have been killed if the law had been upheld… people were denied to live because of government neglect.

Jackson advocated for unionizing and called for class solidarity among the people of Hamlet, stating that the raging fire had no respect for race, sex or religion

and that the people must seize this moment to move from the historic, racial battleground to economic common ground.

Jackson also spoke about the Hamlet fire in his speech at the Democratic National Convention during the 1992 Presidential campaign. Jackson’s political presence after the fire was challenged by local government officials, like Mayor Abbie Covington, of Hamlet.

Governor James G. Martin promised to help those affected. He allocated funds for twenty-four new factory inspector positions and advocated for the creation of a new fire safety division and worker safety hotline. Under the threat of federal intervention from the US Department of Labor, the North Carolina General Assembly also passed fourteen new worker safety laws. These laws aimed to correct much of the deregulation trends of the previous decades. They included stipulations such as protecting individuals who lodge complaints about working conditions and safety, increasing fines for workplace safety violations, and requiring safety training programs for vulnerable businesses such as Imperial Foods.

During the 1992 elections, the North Carolina Commissioner of Labor, John C. Brooks, was primaried and defeated by another Democrat, Harry Payne Jr., who promised labor reform. Payne won the statewide race and served as the Commissioner of Labor for two terms.

Following the fire investigation, the Imperial Foods Chicken Processing plant closed permanently, and the company was fined $808,160 for eighty-three counts of work safety violations. In March 1992, a grand jury also indicted Emmett Roe, Brad Roe, and James Hair -- deputy plant manager at Imperial -- with twenty-five counts of involuntary manslaughter each. However, Caroll Lowder, the district attorney defending the plant workers, accepted a plea agreement in September 1992. The plea agreement exonerated Brad Roe and James Hair from their counts of manslaughter and sentenced Emmett to nineteen years and eleven months in prison. Just one month prior, Emmett declared bankruptcy, as creditors and banks recalled loans to Imperial Foods. The plea agreement made Emmett eligible for parole in March 1994, and he was released from prison in April 1997.

Community members were angered and disappointed by the result. Many felt that the plea agreement made was not proportional to the crimes committed or the loss of life that resulted from their actions, and more were upset that Brad Roe was freely released. Many survivors and their lawyers also sued Imperial Foods, who, due to their bankruptcy, passed the suits onto insurance companies. American International Group, U.S. Fire Insurance Company, and Liberty Mutual Insurance Company paid $16,100,000 in claims to those affected. Additional suits in 1993 by those affected resulted in another $24,000,000 of claim payments.

People in Hamlet struggled to recover from the fire. The plant building remained standing for many years. Eventually, the site of the plant was bulldozed and replaced. Governor Mike Easley unveiled the plan to rehabilitate the plant site as part of the North Carolina revitalization project in December 2001. The city built a memorial park where the plant once stood. In 2003, a memorial plaque was unveiled, dedicated to honor and remember those who died, those who were injured and those whose lives were forever changed on that day.