See also: Public Health; Malaria; Influenza Outbreak of 1918-1919

Before the widespread distribution of vaccinations, many serious, often deadly contagious diseases were commonplace in North Carolina and other American colonies and states. The Carolina colony initially tried to battle epidemics by restricting imports. Passage of the "Distempered Act" in 1755 also barred from the colony immigrants who suffered from "malignant infectious distempers." But these actions proved to be detrimental to the commercial interests of those seeking settlers to inhabit their lands, and the act was repealed in 1760. The Revolutionary War brought the new practice of inoculation to the colonies. This entailed the exposure of a potential victim to a mild case of a disease to prevent further infection. Predictably, the general public was wary of this innovation and its inherent risk of unintentionally causing an epidemic. Only in isolated instances were inoculations routinely accepted and used.

The Moravian settlement in Piedmont North Carolina was probably the first to adopt the practice of inoculation against infectious diseases, causing much trepidation in their neighbors. When Continental troops arrived in Salem in 1779, bringing with them several cases of smallpox, the town conducted an inoculation program that drew the wrath of those in the surrounding countryside. Some "ignorant and malicious" individuals, according to Moravian records, threatened to "destroy" the settlement if the inoculations were given. Soon after the war, James R. Alexander, one of the state's first public advocates for preventative infection, began inoculating his patients in Mecklenburg County against smallpox.

By the turn of the century the practice of vaccination was becoming increasingly common in North Carolina, though not without conflict. In 1800 Calvin Jones unsuccessfully attempted to open a vaccination hospital in Smithfield. The physician's failure was due, in part, to his charge of $10 per vaccination (perhaps the result of Continental dollar depreciation) but was no doubt largely the result of the persistent public fear of the procedure. The prevalence of this feeling is illustrated by the reaction of one community to inoculation. When, in 1801, a well-to-do citizen of Fayetteville returned from Europe with smallpox vaccinations for his family, public outcry forced him to halt his treatment and move his kin to a "remote and private situation."

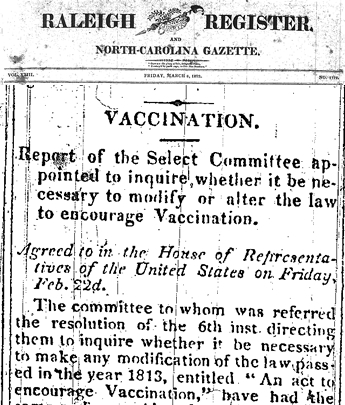

At times the misapplication of inoculations exacerbated this hostility and further damaged the credibility of the procedure. In fact, an event in North Carolina dealt a setback to the national movement toward widespread inoculation. In 1821 James Smith, vaccine agent of the U.S. government, mistakenly sent a packet of actual smallpox tissue, instead of the expected vaccine, to a physician in Tarboro. Unknowingly, the doctor caused an epidemic in using the material. This led to the collapse of the fledgling inoculation campaign in North Carolina and resulted in the ouster of Smith from his position. It was clear that medical science had much progress to make before the general public placed their trust in the inoculation process.

Vaccines to prevent many diseases were developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The General Assembly passed laws to encourage vaccination against smallpox, typhoid fever, and diphtheria, but it was reluctant to enact mandatory legislation. A major campaign against typhoid fever began in North Carolina in 1914, when a state laboratory made and distributed a free antityphoid vaccine. In 1919 third-year medical students, furnished with cars or motorcycles, also administered typhoid vaccines. Thousands of people were immunized by programs run by the North Carolina State Board of Health, which also urged many citizens to ask their own doctors for vaccinations.

The legislature eventually passed laws for compulsory vaccination. A 1939 statute required all schoolchildren to be vaccinated against diphtheria. Of particular concern was poliomyelitis, or polio, which ravaged the state during the 1930s. In 1959 North Carolina became the first state to initiate compulsory inoculation with the Salk vaccine. A 1957 law required children to be vaccinated against diphtheria, tetanus, and whooping cough before their first birthday and against smallpox before enrollment in school.

Despite the availability of vaccines and the mandatory vaccination laws, preventable diseases continued to appear in North Carolina. In 1962 not even one-half of its children were getting the required immunizations before their second birthday. The state's Immunization Activity Project introduced a "birth certificate follow-up program" in 1964. By 1968, 92 percent of the children in North Carolina had begun and 79 percent had completed their vaccinations. The General Assembly passed laws that required children to be vaccinated against red measles in 1971 and rubella in 1979.