See also: Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail

The stunning victory won by a force of about 1,800 backcountry "Overmountain Men" over approximately 1,000 Tories at King's Mountain on 7 Oct. 1780 has been justly described as a key turning point in the American Revolution. According to British commander Henry Clinton, the American victory "proved the first Link of a Chain of Evils that followed each other in regular succession until they at last ended in the total loss of America." The Tory force at King's Mountain was commanded by Maj. Patrick Ferguson, the son of a Scottish judge. At the Battle of Brandywine, Ferguson's right arm had been shattered. However, he practiced so assiduously that he learned to wield his sword with his left hand, earning him the nickname "Bulldog" in the process.

A few weeks before King's Mountain, Ferguson, who guarded Lord Charles Cornwallis's left flank, led a foray to the vicinity of Old Fort in North Carolina. At about that time he bluntly warned the local revolutionaries that if they did not cease their rebellion he would march over the mountains, hang their leaders, and lay waste their settlements with fire and sword. This brought an indignant reaction from the backcountry forces and a conference between Cols. Isaac Shelby and John Sevier, who agreed that they should take the offensive. They called a rendezvous at Sycamore Shoals (now in Tennessee) for 25 September. On that day Sevier and Shelby arrived with 240 troops each to join Col. Charles McDowell, who was already there with 160 North Carolina riflemen. They were heartened when Col. William Campbell marched in with 400 Virginians.

While the little army was marching over Roan Mountain, two of Sevier's troops, James Crawford and Samuel Chambers, were reported missing. Suspecting that they would warn Ferguson, Sevier changed the march plans. On 30 September the American force reached Quaker Meadows in Burke County, where it was joined by Col. Benjamin Cleveland and 350 North Carolinians. By 1 October the Americans were camped just south of King's Mountain. Rain kept them there a day while the officers elected Campbell commander.

Ferguson was also slowed by rain and never reached Charlotte to join Cornwallis, as was his apparent plan. He had not intended to install his army atop King's Mountain, which had allegedly been named for a farmer who lived at its foot and not for King George III. The mountain, with its short and relatively level summit, must have impressed Ferguson as a good defensive position; he wrote to Cornwallis, asking for reinforcements and boasting that he was on King's Mountain and could not be driven off.

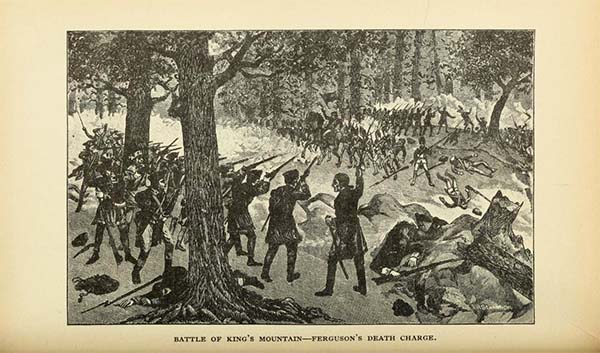

Early on the afternoon of 7 October, the Americans arrived at the foot of King's Mountain, near where it extends into South Carolina. They launched a four-pronged attack, with two columns on each side of the mountain, led by Colonels Campbell and Sevier on the right and Shelby and Cleveland on the left. Ferguson and his men apparently were taken by surprise by the boldness and rapidity of the Overmountain Men's aggression. Over the roar of the battle could be heard intermittently a shrill shriek from the silver whistle Ferguson used to direct his troops. It was soon silenced, however, as Ferguson was killed while leading a desperate sortie by a few of his men to break out of the mountaineers' cordon. Capt. Abraham DePeyster, the second in command, almost immediately raised a white flag. However, several minutes elapsed before the surrender could take effect, and during that period several more Tories were killed. Some Americans kept firing because they did not understand what was going on, and others did so because they recalled that when Col. Abraham Buford, an American, was defeated several weeks before, British colonel Banastre Tarleton had kept on firing, an action Cornwallis had applauded.

Finally the guns fell silent and the American victory was complete. In an hour's time, Ferguson and 119 of his men had been killed, 123 wounded, and 664 captured. The Americans had lost 28 killed and 62 wounded. The Americans were still so angry at their enemies that on their ride home, Campbell found it necessary to issue an order directing the officers to halt the slaughter of prisoners. Finally Campbell convened a court-martial to try some of the prisoners. According to Shelby, 36 men were convicted of "breaking open houses, killing the men, turning the women and children out of doors and burning the houses." Of those convicted, 9 were actually hanged.

The American victory at the Battle of King's Mountain altered the tenor of the American Revolution, disheartening Cornwallis and his army, threatening and eventually altering British military strategy, and adding renewed vigor to the American cause.