See also: Bank Holiday of 1933; Great Depression.

Financial panics and other economic disruptions have had varied effects on the North Carolina economy. The panic of 1786 was an economic slump following the end of the American Revolution. Its most acute cause lay in the new national government's lack of power. The fledgling nation did not have a strong central government with a financial scheme to tax the populace, run the country, or pay the nation's debts. Without the English market or the British pound as backing, the former colonies had a very unstable currency. North Carolina's war debt loomed large, its paper money was worthless, and the market for the state's principal products of naval stores, pitch, tar, and rosin, as well as timber, was gone. In spite of this, the recession did not affect North Carolina as severely as it did other states.

In contrast, the panic of 1819 followed a period that abounded in overspeculation in land, commodities, and stocks. High cotton prices encouraged southerners to buy land at exorbitant prices; westerners were buying land for more cattle; and northerners were building new factories at a brisk rate-all with worthless collateral or no collateral at all. In North Carolina, the three state banks had made excessive loans and could not meet the request for payments to the Bank of the United States in gold, silver, or national bank notes. Low crop prices and hard times hit North Carolina as land values plummeted. Not only were many North Carolinians poverty stricken, they were further distressed by the depletion of the fertility of their soil. Cotton production, the main activity of the state, began moving to the Southwest. North Carolinians blamed deflation and falling land values on the banks. The state came out of the panic with a growing bitterness and a negative attitude toward bankers, a conflict between the creditor and the debtor class that lasted long after the panic.

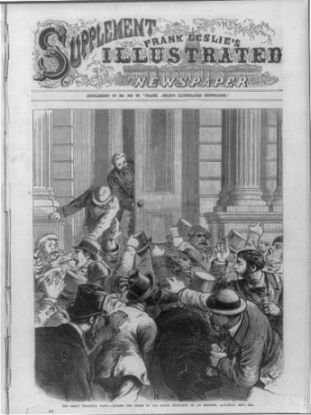

The panic of 1837 triggered a severe national depression blamed in part on the economic policies of President Andrew Jackson's administration. After months of growing uneasiness in the financial world, the banks in New York City, followed by most others in the country, halted specie payments on 10 May 1837. Economic chaos spread, causing widespread bankruptcies and unemployment. The Raleigh Register reported on 2 May 1837 that "great embarrassment" was already being felt in New Bern, Fayetteville, and Wilmington "on account of the Northern failures." The Bank of North Carolina suspended specie payments on 18 May. Falling prices and high emigration lowered the value of farm property in North Carolina and other southeastern states. Farmers forced to sell their property for debts recovered only a fraction of their pre-1837 value; some North Carolinians reportedly got as little as 2 percent of the former value of their farms. The depression sparked by the panic of 1837 lasted well into the 1840s.

The panic of 1857 halted a national economic boom that had lasted since the Mexican War (1846-48), but North Carolina and other southern states were not seriously affected. Similarly, the panic of 1873, triggered by the collapse of several New York financial firms, most severely affected the northern states, which were more dependent on industry and financial institutions than the agrarian South. The economies of North Carolina and its southern neighbors were already in such serious trouble after the ravages of the Civil War, mounting interest on war debts, and high taxes and spending by Reconstruction governments that the panic seemed to have little direct effect on most people.

North Carolina was hard hit by the panic of 1893 and the subsequent economic depression, from which the United States did not fully recover until 1897. Many factors contributed to the severity of the panic, including the trade contraction caused by the high rates of the McKinley Tariff and the fear of investment in the nation resulting from the collapse of Baring Brothers, an English banking firm. As a result, several political and economic changes, at both the national and state level, were instituted. In North Carolina, the state Democratic Party joined the national movement for free coinage of silver. The economic situation did not improve significantly until 1897, when poor European crops stimulated American exports and gold importation.

The panic of 1907 was one of the most severe economic downturns in the history of the U.S. business cycle, ranking second only to the Great Depression in how sharply output fell during any twentieth-century recession. Although severe, the downturn was short lived, with the panic ending and the economy getting back on track quickly in 1908. The panic of 1907 was the final episode of financial instability that convinced legislators of the need for a central government monetary authority.

The panic of 1929, which began in October, is usually regarded as the beginning of the Great Depression, although the business cycle began its downturn in August of that year. In the latter part of the 1920s, the Federal Reserve became concerned that the stock market was overvaluing assets and that these asset values were not reflective of true market fundamentals. The combination of tight money and a weakened economy took its toll on the stock market on 23 Oct. 1929. The result was, in percentage terms, the second-largest one-day fall in the market as panic selling hit Wall Street. The panic had left the banking system vulnerable to a continued weak economy as depositors liquidated assets, and the economic uncertainty generated by the crash of the stock market further weakened consumer and business spending and accelerated the economic slide. North Carolinians, along with millions of other Americans, were hit hard by the economic and social woes brought on by the panic of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression.

The introduction of bank deposit insurance in 1933, along with changes in the Federal Reserve system and a better understanding of the root causes of financial panics, helped to eliminate these events from the U.S. economic system.