When William Henry Belk and his brother John Belk opened their first department store in Charlotte in September of 1895, the idea of buying everything under one roof -- and always for cash, not store credit -- was new to consumers. This excerpt from the history of Belk, Inc., tells the story of Henry Belk, his first store in Monroe, and the Belk Bros. stores in downtown Charlotte.

It began at the New York Racket

Farmers had money only once a year, when they sold their crops at harvest. To survive and keep food on their tables and seed in their felds, farmers depended on credit from country merchants. Many merchants took advantage of their captive customers and increased the price of goods sold on credit by 20 to 50 percent and then charged interest on the outstanding balance. When farmers arrived to settle their accounts at harvest time, they sometimes found themselves paying 40 to 100 percent more than if they had paid in cash.

William Henry Belk had seen this system work, both as a merchant and earlier as his mother had struggled to revive the family's farm. Such a system left customers with overpriced goods and their dignity ground into the Carolina clay. Merchants, meanwhile, were caught in the middle, risking their own futures to keep farmers in business. Neither condition suited Belk.

Belk had heard about another way of doing business. In 1878, a merchant named John Wanamaker in Philadelphia had opened what he called a "New Kind of Store" that incorporated a one-price system. Instead of customers negotiating prices with a merchant, goods were plainly marked and sold at the posted price. Wanamaker was not the first to adopt the one-price system—Lord and Taylor in New York had used it as early as 1835—but he was the first to implement it on such a large scale. Traveling salesmen who carried trade news from town to town, as well as advice on stock and a few tall tales, told Belk that Wanamaker's plan was founded on four principles: in addition to selling goods at a fixed price, Wanamaker sold for cash and didn't offer long credit; he also offered a generous money-back guarantee and was totally committed to satisfying his customers.

Wanamaker's success with one-price shopping worked in Philadelphia where customers had steady incomes from factory paychecks and office jobs; a person's income wasn't dependent on the weather and changes in the price of cotton. North Carolina, however, remained tied to the farm economy. There was no guarantee that cash-only sales could be transplanted to a town like Monroe, where credit terms and haggling over a merchant's asking price were accepted parts of the business. Henry's friends told him he was foolish to try something different, but he persisted, and on May 29, when he opened the doors of the New York Racket, he announced this new policy.

Belk told his customers that if he didn't have to carry their debts, his goods would be cheaper than what they might find at his competitors' stores. He could take advantage of his discounts from vendors who normally gave him 5 percent off if he paid bills promptly. The policy meant turning over a lot of stock during the year, but he was prepared to take the chance. He carried through with his lower prices, sold for cash only, and promised full value and full service. If a customer was unhappy with goods, he knew Belk would make good on the sale without any questions. This strategy made sense economically, and it fit comfortably with Belk's own Scots-Irish independence. If a man paid cash for his goods, Belk said, he would be happier than if he had a debt hanging over his head.

As 1888 came to a close, Belk tallied his accounts after six months of business. His books showed sales of just more than $17,000, an average of $100 a day since he had opened his doors. He had repaid the $500 loan, paid Captain Austin for his goods, and restocked the store. He had a profit of $3,300. Belk's strategy not only had worked, it had worked well. The New York Racket was a success.

The promise that more could be achieved sent Belk to Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New York, where he scouted out bargains, close-outs, bankruptcy sales, and deals from merchants on the narrow streets of Manhattan. The eager young man from the South won friends easily in the market and established relationships with merchants who were still selling to him thirty and forty years later. Years of listening to salesmen had provided an education beyond what he could have found in a college classroom. Experience had taught Belk how to buy. He knew the prices of raw materials and what labor was involved in making a pair of shoes or a shirt. As a result, he bought well. When the goods arrived in Monroe, Belk sold them straight from their heavy wooden packing crates. With each sale he turned a small profit, and he was soon back on the road again. His slogan was "Cheap Goods Sell Themselves." By the time the decade closed, sales at the New York Racket had more than doubled.

As the business grew, Belk hired more clerks, but he needed someone who could tend the store in his absence, in whom he could have absolute and unqualified confidence to serve customers as well as he did. In 1891 he paid a visit to his brother, John, who for five years had been building a country doctor's practice thirty miles east of Monroe in the Anson County town of Morven. John had married two years earlier and begun a family. Times were tough, but he had earned enough to repay a portion of the money he had borrowed from his brother for his education. On a particularly difficult night, after John had returned in bad weather from tending a neighbor's maladies, he made his pitch. Leave medicine, he urged his brother, and come into business. They talked it over through the night. By daybreak, John had decided that his future was in retailing, not medicine. John took a one-half interest in the business and moved to Monroe with his wife and young daughter. As soon as a painter could be found, the New York Racket sign came down and was replaced by one that read "W. H. Belk and Bro."...

Elegant new garb

William Henry Belk was ready to sell anybody anything. His store was a combination of services, part novelty and part dry goods, which aimed for the business of the solid, hard-working people in the community and in the county. He promoted one-cent items—pencils, fishhooks, matches, blacking, marbles, sheets of paper, soap, and buttons—but his stock was heaviest in overalls for the well-digger, spectacles for the grandmother, and suits for Sunday meetings. Belk had a feeling for the working people. He knew they wanted high-quality goods for their hard-earned dollars. He had given them that in Monroe, and he found that shoppers in Charlotte weren't much different.

He searched for ways to promote his trade in the city and beyond. When country folks came to town to load their wagons with supplies, he arranged with some to have a Belk sign painted on the side of their wagons in exchange for extra bolts of cloth. The painted notice helped, to be sure, but perhaps more important was the word of mouth that spread in the surrounding communities about the values to be found in Belk's store, where every customer was king. Belk's strategy was simple: sell the working man necessities like sturdy work shoes at a low price, and he would return to outfit his entire family.

Christmas brought a new level of success. The Belk brothers' stores were doing well: forty employees in the four locations were needed to handle the business. Although others also sold staples at low prices for cash, William Henry Belk held his own against stiff competition. He crowed about the large crowds in his Christmas ads and by the year's end had adopted a new slogan, "Goods sell themselves because they are bought right. That was but a slight variation of the slogan printed on the invoices of the New York Racket — "Goods Cheap Enough Sell Themselves." When the brothers settled their accounts for 1895, they knew they had made the right decision to expand to Charlotte. The Monroe store was doing well under John's management, and the two stores in South Carolina were growing, but Charlotte moved the Belks into a league that neither had believed possible. In 1894, with three stores in small towns, the brothers had sold more than $50,000 in goods. Sales for 1895 were six times that. With Charlotte added to the group of stores, the brothers had generated more than $326,000 in sales.

Soon other Charlotte merchants were imitating Belk. S. T. Cooper's Bee Hive, just a half-block away at the corner of Trade and College streets, adopted the slogan "The Cheapest Store in North Carolina." Another competitor, Williams and Hood Company, under the name of the "Old Racket," used price to counter Belk. Using the same typeface and advertising style, Hood said in the Observer , "We buy our goods cheap and sell them cheap. The field of credit disaster, the slaughter pens of the sheriff and the auction rooms are our prolific play-grounds."

Belk replied by upping the ante. He opened a "bargain shoe counter" and offered to outfit men, ladies, misses, and children at even lower prices. He negotiated with manufacturers and mills in the area for bargains on piece goods and the best fabrics. His shoes came from Craddock-Terry Shoe Corporation in Lynchburg, Va., which started business in the same year that Belk opened his first store in Monroe. Belk also shopped the Cannon mills in Kannapolis and even invested in textile operations and other enterprises that kept him close to the demands of the market. He added mail-order service and favored one-cent items, from fishhooks to marbles, that helped draw young customers into the store. And he often worked as his own "puller-in," standing at the front doors chatting with passersby and inviting them into his store.

By 1897 Belk had established a loose cooperative buying network that tied together the purchasing power of the Belk stores in Charlotte, Monroe, Union, and Chester, as well as two other stores in which the Belk brothers had no financial interest. They purchased goods in large lots and passed the savings on to their partners. A buyer in New York scouted the market on their behalf to find bargains in hats, for example, and the Belks bought as many as fifteen hundred pairs of pants at once....

Customers would find the Belk brothers all over their stores. They were the first in the building each morning, organizing the display tables and merchandise for the day and supervising the young check boys as they swept the floors and pulled the tarpaulins off the display tables. Bolts of cloth, stacks of men's denim jeans, and other goods were placed on upended wooden shipping crates on the sidewalk. Throughout the day, when clerks were overrun with business, Henry waded into the crowd of customers, eager to sell and thriving on the exchange with people. He always carried a small pair of scissors in his vest pocket, which he used to snip the corner of a measure of cloth before he tore it across with a flourish. The brothers remained on duty until the late evening hours. Closing time was simply a function of the traffic and the competition; no store wanted its selling floor dark when another store up the street still had bright lights burning for customers.

Such a schedule was nothing new to Belk. B. D. Heath had taught him the rudiments of retail clerking when he was fourteen. Moreover, Belk had been raised in a simple home marked by early years of severe economic hardship. Hard work had been a necessity as well as a virtue honored daily with Bible readings. As a young man, he had always carried a portion of his pay home to help put food on his mother's table, pay off the mortgage on the farm, and later to pay for his brother's education. He took these lessons learned from his mother to Charlotte, where they were as much a part of his business as cash sales and low prices. Indeed, Henry seemed all but consumed by his efforts to retain an edge over his competitors. His clever ads helped, but his success was due to a keen eye for opportunity and a single-mindedness of purpose.

Except for trips to markets in Northern cities and excursions into the Carolina countryside to buy from the growing textile concerns in the Piedmont, Belk didn't stray far from his store on East Trade Street. He lived in rooms on the upper floor of the taller of his two buildings and took his meals across the street at the Central Hotel. Many of the city's businessmen and most travelers who visited it found substantial, well-cooked food there. Businessmen, including bachelors like Belk and newspaper editor J. P. Caldwell, listed the hotel as their residential address. After dinner, Belk passed the time with the others at the hotel before returning to the store to prepare for the next day's business. He had counters to restock, accounts to settle, and another round of advertisements to write....

As word of the brothers' success spread, it brought more customers and, more important, a steady stream of young men eager to leave the farm and follow Belk's example. The two were partial to the ambition they found in farm boys who showed up at their stores asking for work. They knew life on the land had tempered these young men to long hours and tough duty, and the brothers knew just how much they wanted to succeed: their alternative was a return to following a mule across acres of Carolina clay. The Belks also knew the families these young men represented. The first candidates for apprenticeship were cousins or close family members. Ralph J. Belk, for example, opened a store in Waxhaw in 1897, just like their cousin's husband Alex W. Kluttz had in Chester. Although these new men weren't blood kin, Belk was familiar with their families through his years in the area and his work with the Presbyterian Church. Before long, the Charlotte and Monroe stores would become a reservoir of such talent.

The communities growing up around the new textile mills along the rail line offered the perfect opportunity for expansion. The process was simple enough. In Greensboro, for example, the brothers found a suitable building located on the corner of Washington and Elm streets a few blocks north of the railroad, laid in a stock of basic dry goods, and opened the door. But this move was different and set the stage for a pattern that would continue for more than fifty years. Located about a hundred miles north of Charlotte, Greensboro was developing into a major textile manufacturing center. In 1899, the Belk brothers prevailed upon D. R. Harry of Charlotte, who had once worked in the Charlotte store, to leave his insurance business and take a one-third interest in a new company they planned for the Greensboro store. The brothers knew the young man could sell—they had trained him. And they knew that he came from a hard-working family. Another brother, Sam Harry, had clerked in the Chester store before opening his own business in Salisbury in 1894, and they had helped put his brother Reece in business in Union. In early 1899 Dick Harry agreed to the Belks' proposition, and in March the Harry-Belk Brothers Company opened for business.

Two years later the Belk brothers looked west across the Catawba River, where the textile industry was rapidly changing Gaston County. Gastonia, the county seat, was humming with business. More than four thousand Gaston County workers were employed in nearly one hundred manufacturing plants in the county. The city had replaced the oil lamps along Main Street with electric lights, and the same bond issue raised money for a municipal waterworks. Gastonia had been transformed from a rural farm market into a factory town with steady wages and a solid economy. Only the Gaston County liquor distilleries seemed to be in trouble, but that was just fine with the Belks, who preferred to count the number of churches in the communities where they did business. On February 25, 1901, Will Kindley opened Kindley-Belk Brothers Company on Gastonia's Main Street in a small two-story brick building not much larger than Henry Belk's first store in Monroe. Within a few months, however, business increased and Kindley added five more salespeople to his original staff of three. And the staff got raises: some of the first records of the Belk network of stores show women now earned seven dollars a week, instead of five; the men's pay went from eight dollars to ten. The check boy got a quarter a week....

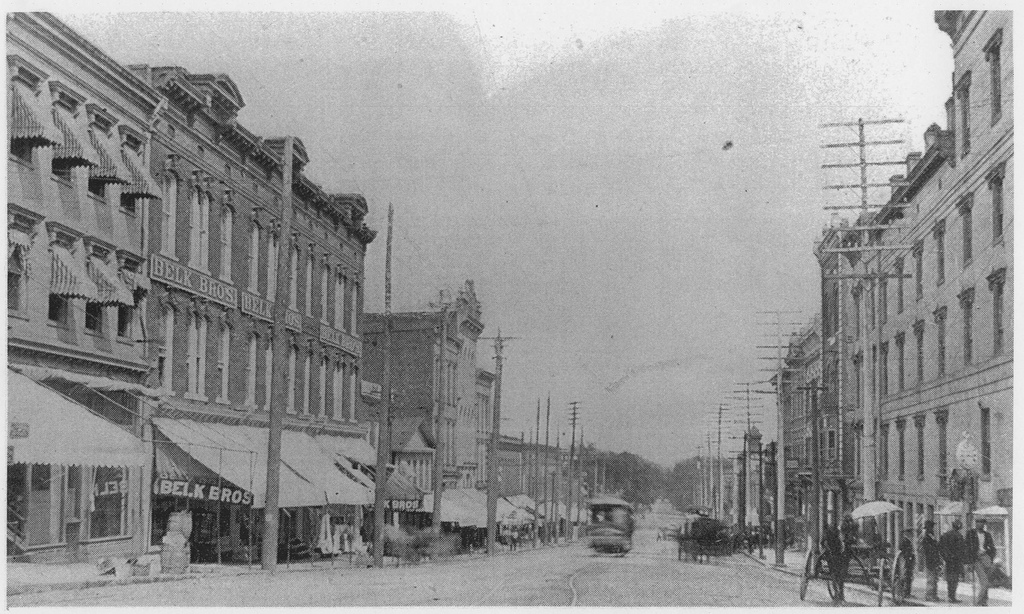

In 1910, sales at the brothers' stores were approaching a million dollars a year, and the Belks had perhaps their boldest effort yet laid out on the drawing boards of architects Oliver D.Wheeler and Eugene J.Stern. Two years earlier and twenty years after Henry Belk leased a meager two thousand square feet of space on a dusty Monroe street, he and his brother had commissioned plans for a new five-story building to house their Charlotte store. They planned to keep the men's store in the building that Henry had leased from Colonel Davidson when he opened in 1895, plus one adjacent building, but most of the store would be housed in a new structure that would rise beside these buildings and be the finest department store in town.

On October 4, 1910, Belk announced to the readers of the Charlotte Observer that the Belk Brothers store on East Trade Street would close on October 5 and reopen at 8pm on Thursday, October 6, with an "informal reception" for the city's newest business address. The Observer's reporter was overwhelmed by what he found as he joined the crowds that turned out to see the Belks' new store. "It might be regarded," the writer said in the morning paper, "in a sense as a debut party, in which Belk Bros. store was introduced anew to the people of Charlotte and surrounding towns in its elegant new garb."

Despite a light rain carried over the city by warm southerly winds, more than 2,500 turned out to stroll the aisles and view the merchandise Belk and his buyers had purchased for the special occasion. Just inside the front door, a large staircase led to the basement, where toys and holiday goods were laid out on tables along with bargain merchandise. Carpets, rugs, and home furnishings were on the third floor. Ladies'clothing on the second floor was under the close watch of Sarah Houston, whose word even Henry Belk never disputed. Houston commanded her position as firmly as Frank Matthews did his in menswear, still located next door in the original building. On the main floor shoppers found woolens, linens, notions, ladies' accessories, and hosiery. William Henry Belk's desk was on a mezzanine from which he could survey all below.

Charlotte was ready for the new store. The city was bursting with pride over its growth, and "modern conveniences" were readily available for the new homes in the suburbs. The newspapers advertised new appliances such as the "suction cleaner," a vacuum cleaner that came with sixty-five feet of cord, and the Charlotte Gas and Electric Company was presenting free lectures for cooks on the proper handling of a gas range. A Ford Roadster cost $680. The Belks' grand opening sale featured ladies' suits for $18.95, nickel handkerchiefs, and Sarah Houston's best selection of millinery, wraps, and coats. Not to be outdone by the Belks' new store, Little-Long Company announced that the forty showgirls appearing in the musical "The Girls behind the Counter" would be in their store to serve customers.

The opening-night rain continued into Friday and through the weekend. Unperturbed, Belk extended his grand opening sale another week. When the skies finally cleared and the sun broke through over Charlotte, Belk could look across Trade Street from his table at the Central Hotel and see reflections off the new copper facing and shiny prism glass that decorated the storefront. Just above a high tier of windows, the name "Belk Bros." was set firmly in terra-cotta, flanked by ornate cartouches featuring a large capital B.

Source Citation:

Covington, Howard E. Belk, Inc.: The Company and the Family that Built it. Charlotte: Belk, Inc, 2002.