The following interviews are from the Southern Oral History Program Collection at UNC Chapel Hill. This series on rural electrification tells us more about this federal program affected people in North Carolina.

Interviews on this page: Lena Boyce | Shirley Collier | Hubert R. Prevatte | Sam H. Ostwalt

Lena Boyce

Lean Boyce interviewed by Sue Beal, October 16, 1984.

Sue Beal

Did you have any electrical appliances before you had the current turned on? Did you just have the lights first?

Lena Boyce

Mr. Boyce had him a radio already. He ordered it from Sears and Roebuck. It came in on the morning mail, and they came and turned the current on that night just before sunset.

Sue Beal

That's interesting. Do you remember the date?

Lena Boyce

No I do not, but it was in the spring of the year. First part of '41 if I remember correctly.

Sue Beal

He had already bought his radio. He was ready for that. Did you have a battery operated radio before then?

Lena Boyce

Yes, we had a battery-operated before then.

Sue Beal

What were the first appliances that you purchased for your house?

Lena Boyce

Well, one of the first things was a better refrigerator. We've always liked to eat here [laughter], and Mr. Boyce 'specially wanted one so he got a refrigerator not too many months after power came in. Got the Radio. Right now I just can't recall. I believe an iron, maybe that was one of the first things.

Sue Beal

You shared a little story with me earlier when I did that article on you about when the lights were turned on and what you thought about your house. Can you share that with me again?

Lena Boyce

I won't ever forget that. We turned it on in the kitchen, we were in the kitchen getting ready to eat supper (they'd finished up out here, turning the current on), and Mr. Boyce came in and put the light on to eat supper by. And my kitchen walls looked so dirty! I just couldn't believe it. The lights were so bright, so much brighter than what we'd ever had in there before. During the day we had sunshine and all that, but yet it didn't come in the house like the electric light did.

Shirley Collier

Shirley Collier interviewed by Renate Dahlin, June 4, 1985. Ms. Collier's home received electricity in 1945.

Shirley Collier

We had an old woodburning stove. That was beautiful, it was cast iron. You had your little poker things that you start the fire with, that you pick up your little top burners. That's how we had to cook.

Renate Dahlin

You used only wood, or coal?

Shirley Collier

We used only wood. And our only means of heating was the fireplace. We had a fireplace in the kitchen and in the livingroom and a back bedroom.

Renate Dahlin

In one bedroom? And the other seven?

Shirley Collier

The other seven didn't have any. No heat, whatsoever.

Renate Dahlin

What did you use for light?

Shirley Collier

We had lamps and my aunt had her lantern that she carried with her constantly. Oil lamps. You had to wash the shades every day.

Renate Dahlin

When you went from one room to another, you carry your lamp with you?

Shirley Collier

You carry your lantern then because it was completely covered and the wind wouldn't blow it out.

Renate Dahlin

Did you have the bathroom outdoors still?

Shirley Collier

Oh, yeah, we had the outdoor bathroom. Bathroom was about 50 yards from the house because you didn't want it real close. We had no running water, but had a pump outside the kitchen. It was a deep well pump. And we carried everything from the pump to the kitchen, to the barns, whatever we used water for we had to carry it....

Renate Dahlin

What did you do to keep your food from spoiling?

Shirley Collier

Well, there were so many of us that it never got a chance to spoil (laughter). Our meat was salt-cured and sometimes smoked so that didn't spoil. When we killed hogs in the wintertime we had meat until it run out and you had your fresh vegetables and stuff in the summer. And occasionally, you'd kill a chicken and have your meat on Sundays or else you could afford to buy some type of meat, which was more or less stew beef which you made that day and you ate it.

Renate Dahlin

What about milk? Did you have your own cows?

Shirley Collier

Yes, we had our own cows. The cow was milked every day and my grandmother used to make what she called clabber. And they ate that with biscuits but that was something I never did even as a child. I didn't want clabber; it just didn't look appetizing to me; I guess because I knew it was mainly spoiled milk....

Renate Dahlin

What do you remember about when electricity was installed? Did you see the men out there working? Did you watch?

Shirley Collier

I saw them out there the day before, and we were all so excited the next day in school that we couldn't hardly sit down. Couldn't wait to get home and turn on them lights, 'cause we thought it was going to be something terrific you know. To just pull a switch, which is what we had. We had the ones you hang a string on or chain and you pull it. We didn't have the wall switches. I know we probably pulled them a hundred times a day 'til we got used to it.

Renate Dahlin

So one day you came back and there was electricity… But it was daylight, I'm sure.

Shirley Collier

Yeah, but we pulled the switches anyway. Had to see how many lightbulbs worked.

Renate Dahlin

How many lights did you have? Did you have light in every room?

Shirley Collier

No, we had a light in the kitchen. We had a light in the bedroom, the bedroom that had the fireplace which was, naturally, Grandma's and Grandpa's. And we had a light in the living room, which they called the parlor. And we had one light in my mother and father's bedroom. But the other rooms, we didn't have lights in 'cause they were just for sleeping, as Grandpa put it.

Hubert R. Prevatte

Hubert R. Prevatte interviewed by Rose Prevatte, June 19, 1984.

Rose Prevatte

What are some of the things you remember when the lights were first being strung?

Hubert Prevatte

It created a considerable amount of excitement throughout the neighborhood. We had worked hard for two years trying to secure the power lines in our area. We had made application repeatedly to Carolina Power & Light Company, who had power in Pembroke, two miles from us. But they refused repeatedly to extend lines out into our area because they felt we were not able to pay the bills if we had the lines. And they were not willing to make the investment with no more assurance than they had of making a profit on the investment.

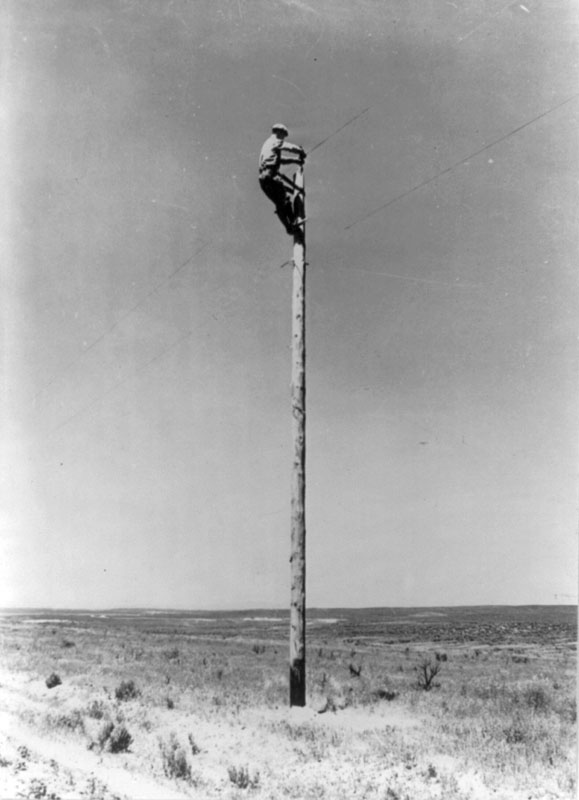

So, it was something we had worked at for at least three years, trying to secure enough people, the required number of people to get the line established by REA. There was a requirement of three members to the mile that we had to meet. And it took hard work, pretty much persuasion to secure this three people to the mile, because so many of them were not interested at all. Particularly, my own parents. They were not interested in securing electricity. They had lived their lives without the use of electricity and they were not anxious for electricity at all.

I used to work in the fields hard all day. Then after supper walk to the neighbors, a mile sometimes, to try to secure enough people to make the requirement of three customers to the mile. I did that night after night over a long period of time.

And naturally when we got the lines we were just thrilled to death; we were being rewarded for all our efforts. So, it created a lot of excitement. Children in the neighborhood came out to watch the construction of the lines. Their dads were glad to help out in any way. In one particular instance I recall I took my own team of horses and pulled lines through the Lumbee River Swamp in order to get them there, because the cooperative did not have equipment at that time to go over these rough places. And when we got to the river with the lines then the neighbors got together with the construction crew and pulled the lines by hand across the river, swam the river and pulled the lines across. So that's the things that I remember most so far as when the first lines were built.

Rose Prevatte

What was the charge for a membership back then?

Hubert Prevatte

I think it was five dollars - it was either three or five dollars, I don't recall. We had a basic charge of three dollars a month, I do remember that, if you didn't use over sixty kilowatt hours. And of course, we were careful not to exceed that because it was hard for us to pay three dollars a month then. We very seldom in the beginning, exceed that....

Rose Prevatte

You said your community had tried to get private utilities to provide electricity to your area and that you didn't get much response from that.

Hubert Prevatte

Didn't get any. We were just told flat that we could not get it from Carolina Power & Light Company. So we got together in meetings at night, had meetings at night and made application to REA for the power and Congress had appropriated money to loan to cooperatives for such use. And that's the way we got our line built, through an appropriation of Congress and the availability to build the lines.

Sam H. Ostwalt

Sam H. Ostwalt interviewed by Robert (Dusty) M. Rhodes, September 19, 1984. Mr. Ostwalt's home received electricity in 1939 or 1940.

Dusty Rhodes

Do you remember that first day, that first night that you got electricity?

Sam Ostwalt

I certainly do. We had put a pump in a the spring. It's a thousand and twenty feet to the homeplace and a hundred and one foot rise. And we didn't know what to set that pump on to pull the water out of the springs. So the electrician come out here with me. We went to the spring when they turned the power on and took a shotgun; left the shot gun up here at the house and told him when the water started running out of the spigot to shoot that gun and let us know how much pressure we had to have to run water up to the house.

Dusty Rhodes

Communication by shotgun (laughter)

Sam Ostwalt

Takes fifty-two pounds of pressure to bring it up to the house.

Dusty Rhodes

So you got water coming into the house. That was the first thing.

Sam Ostwalt

That was the fist thing. Then lights. My goodness, it was wonderful. It was just like daylight, almost.

Dusty Rhodes

What happened that first night when the sun went down and you didn't have the yellow kerosene lamplight?

Sam Ostwalt

Well, we just all felt so good and rejoiceful that we thanked the Lord for it.

Dusty Rhodes

Your mother was still living then?

Sam Ostwalt

Yes, mother was still living. She didn't' die until Fifty-four. She was nine years younger than my dad.

Dusty Rhodes

So I guess it was a special day for her.

Sam Ostwalt

Special day for her. It made it a lot handier for her, too, you know. She'd been used to doing everything the hard way, and that was a big help to her.

Dusty Rhodes

What was the impact on her, say, in the kitchen? What could you see that made her life easier?

Sam Ostwalt

See, we had to have a big icebox outside, and she had to go out there. Had a cable on it with a weight on it to help her lift that heavy lid. Put three hundred pounds of ice in there so we could keep our stuff cool. And she didn't have to do that after we got electricity. She had a refrigerator. All she had to do was open the refrigerator door. It made it a lot easier for her.

Dusty Rhodes

Well, you said a pump was the first appliance you got. Was a refrigerator the second?

Sam Ostwalt

We had a refrigerator ready; it was ready to go.

Dusty Rhodes

You already had it?

Sam Ostwalt

Yes, sir.

Dusty Rhodes

What were some of the other first appliances?

Sam Ostwalt

Well, we still used the cookstove for a while. Mother kinda wanted to keep that. Finally changed over to the electric stove then.

Dusty Rhodes

I understand biscuits taste better cooked in a wood stove.

Sam Ostwalt

Oh, they were good. They were good (laughter).

Dusty Rhodes

What were some of the other appliances then?

Sam Ostwalt

Of course, we had to have a radio, too, you know. Wasn't any TVs. But we had to have a radio. We didn't use any electric iron for a while, but finally got to using an electric iron.