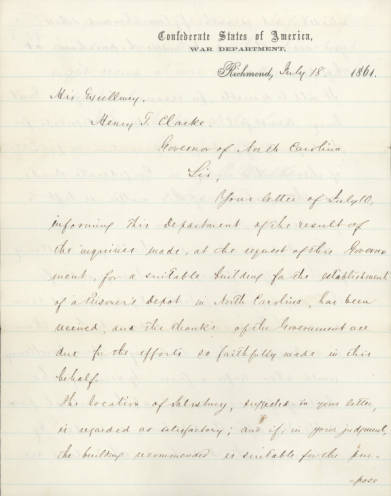

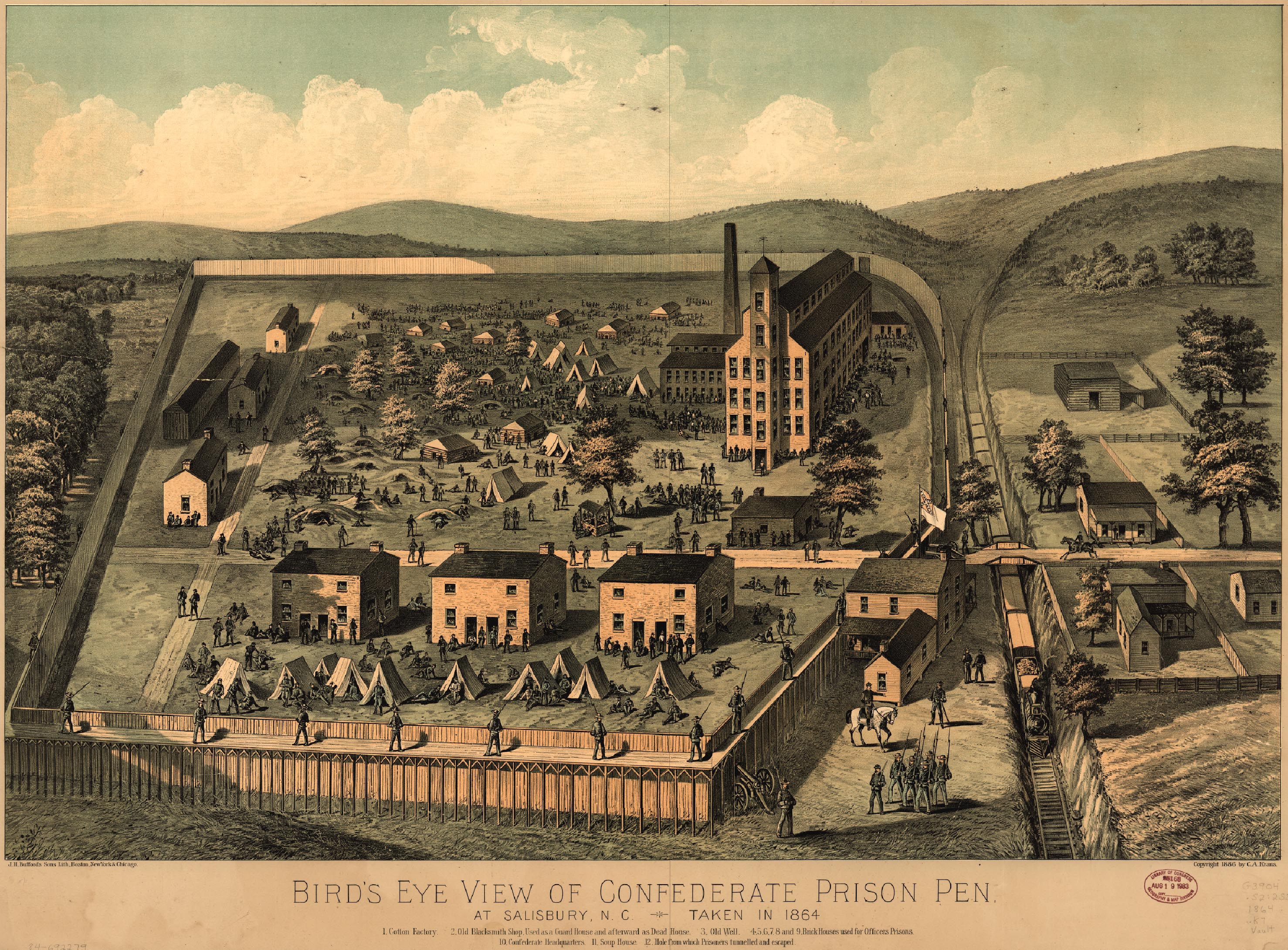

During the early days of the Civil War, the Confederacy, unprepared to confine Northern prisoners of war and deserters or Southern deserters and dissenters, housed these men in jails and abandoned buildings. In July 1861 the Confederate government appealed to the states for a prison. North Carolina, the only state to offer a prison, suggested the site of a former cotton factory in Salisbury. Its location on a rail line would facilitate prisoner movement. The main structure, a four-story brick factory, and accompanying wooden buildings would sufficiently house the anticipated two thousand inmates. On November 2, 1861, the Confederate government purchased the sixteen-acre site. Guards were hired, and repairs and modifications to the site were made. On December 9, 1861, the first 109 Union POWs arrived. By May 1862 Salisbury Prison held more than fourteen hundred inmates.

The inmates enjoyed good conditions initially. Food, water, and space were plentiful. Religious services took place each Sunday. The men performed in concerts and theatrical routines, and played chess and cards. Some made trinkets to pass the time. But their favorite activity was baseball; they played nearly every day the weather allowed.

In late May 1862 negotiations resulted in the parole to the Union of about fourteen hundred POWs. Salisbury Prison held few inmates until October 1864, when thousands of captives began arriving. On November 6, 1864, the prison held 8,740 inmates, the largest number at any one time and far more than the 2,500 for which it was designed. Conditions quickly deteriorated. Inmates faced overcrowding, poor sanitation, meager rations of food and water, vermin, inadequate medical care, and lack of warm clothing and heating fuel. Tents and dugouts in the ground served as makeshift shelters as buildings were converted to hospitals for the growing number of sick. Up to twenty men a day died in the fall of 1864 owing to these harsh conditions.

Prison workers, although frustrated by the conditions the POWs faced, could do little to alleviate the situation. The workers themselves, particularly the guards, were ill clothed and ill equipped because of shortages. Food, water, and other staples were in short supply throughout North Carolina and the Confederacy, and the public and Confederate government complained if precious commodities went to the prison rather than to the troops.

Many captives attempted to escape from Salisbury Prison, often by tunneling under the fence surrounding the prison site. The most ambitious escape attempt occurred on November 25, 1864, when captives rushed the prison gates, wrenched guns from the guards, and tried to run into the surrounding woods. The guards fought back, firing a cannon three times and recapturing the men, who were weak from lack of food. About 250 men, including several guards, died in the desperate escape attempt.

On February 17, 1865, the Confederate and Union governments announced a general POW exchange. Over the next three weeks, more than five thousand prisoners left Salisbury. The sick went by train to Richmond; the able marched to Greensboro, and then went by train to Wilmington, where on March 2 they were officially exchanged for Confederate prisoners. Only a few civilian prisoners and those too sick to be moved remained in Salisbury Prison.

Confederate officials debated the future function of Salisbury Prison, deciding it should be used for urgent needs. But on April 12-13, 1865, before the site could be put to use, Union general George Stoneman and his army burned the prison buildings and destroyed much of the property.

Between November 1861 and February 1865, Salisbury Prison held about fifteen thousand prisoners. Approximately four thousand men died because of poor conditions. In 1867 the site became a national cemetery honoring Union soldiers who died in the prison. The United States government in 1873, the state of Maine in 1908, and the state of Pennsylvania in 1909 erected memorials at the cemetery. Today, visitors taking the Salisbury Civil War Sites Driving Tour can see the prison site, a remaining guard building, and the national cemetery.

Source Citation:

"Salisbury Prison: North Carolina's Andersonville." North Carolina Civil War and Reconstruction History Center. Accessed April 4, 2022. https://nccivilwarcenter.org/salisbury-prison-north-carolinas-andersonvi...