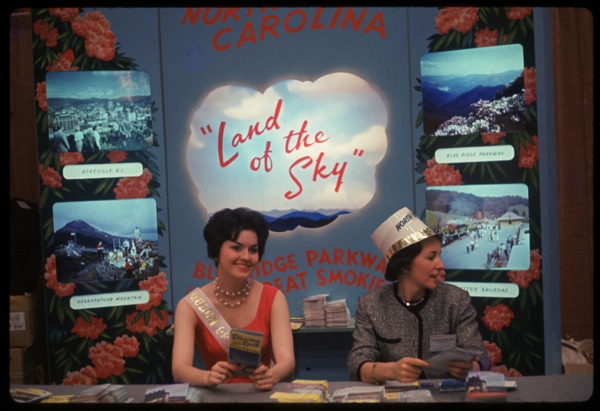

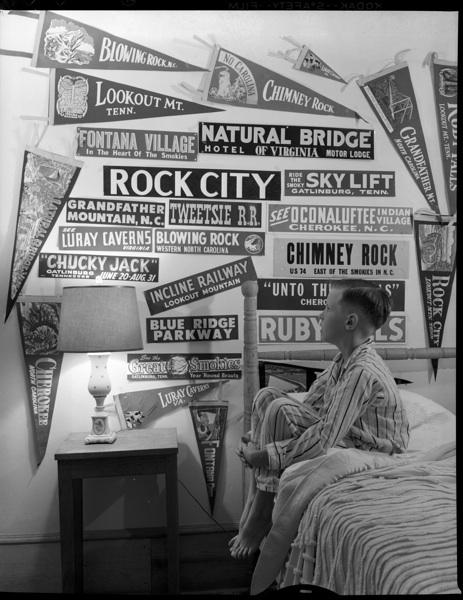

In 1937, the new Division of State Advertising launched a comprehensive campaign to attract more visitors -- and their money -- to the Old North State. Labeling the state a "Variety Vacationland," this program included print advertisements in leading newspapers and magazines, pamphlets, guidebooks, billboards, and even a feature-length film, all designed to sell the state to potential visitors. North Carolina clearly had much to offer tourists. Pristine beaches in the east and majestic mountains in the west provided a rich landscape for tourists to hike, fish, or simply lose their cares in the great outdoors. Other attractions like the golf courses of Pinehurst, the lighthouses of the Atlantic coast, or any of the state's historic sites offered visitors a litany of cultural and recreational diversions.

But, these efforts were about more than simply extolling North Carolina's virtues. This program marked a concerted effort to establish a distinctive image for the state in the minds of the traveling public. Tourism, even in the 1930s, meant big money. Just after the "Variety Vacationland" campaign began, state economic officials estimated that tourists brought about $50 million to the state which, they claimed, "amounts to more than the entire return of the cotton crop and about one third the value of the tobacco crop." For a state still mired in the depths of the Great Depression, that type of money represented hope for a better economic future and that hope rested on crafting an appealing, marketable image for North Carolina.

Although this new campaign sought to stoke the fires of tourism, North Carolina's variety of landscapes and attractions had drawn leisure travelers for quite some time. In the early nineteenth century, wealthy planters such as Wade Hampton and future Confederate treasury secretary C. G. Memminger sought solace from "the fever season" at North Carolina retreats in places like Cashiers and Flat Rock. Communities like Hot Springs became bustling tourist destinations before the Civil War.

After the war, tourism emerged anew. While some North Carolina communities turned to textiles, tobacco, or furniture as routes to post-Civil War prosperity, other looked to tourism to carve out a place for themselves in the New South. Just as in the twentieth century, image making and tourism went hand in hand in post-Civil War North Carolina.

For example, city leaders in Asheville seized on the moniker "the Land of the Sky" -- first coined by novelist and travel writer Frances Tiernan -- to evoke images of pastoral mountain landscapes in tourists' minds, an image the city continues to use in its promotional efforts. Even in the late nineteenth century, tourism rested on promoting a destination to visitors and giving them something to do when they arrived. In short, tourism relied on creating an image and trying to make that image a reality, at least in the eye of the beholder.

By the twentieth century, the Outer Banks, the links of Pinehurst, and mountain destinations from Linville to Sapphire Valley drew growing numbers of visitors, first arriving by rail and, by the 1920s, by car. Tourism evolved to be more than a route to economic development. It became a catalyst for a myriad of changes that shaped the state and reinforced the Old North State's reputation -- deserved or not -- as a bastion of progressive ideals. Tourism promoters helped to lead the "Good Roads" movement which would establish one of the best state highway systems in the South.

Those concerned with preserving the state's natural spaces helped establish the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and the Cape Hatteras National Seashore. Tourism also aided in historical preservation efforts, helping to save individual historic structures as well as providing a catalyst for establishing state and federal historic sites such as such as the Thomas Wolfe's boyhood home in Asheville and the Bentonville Battleground State Historic Park. By the 1950s, North Carolina emerged, with the help of the images evoked by the "Variety Vacationland" campaign, as one of the South's most popular and diverse tourist destinations.

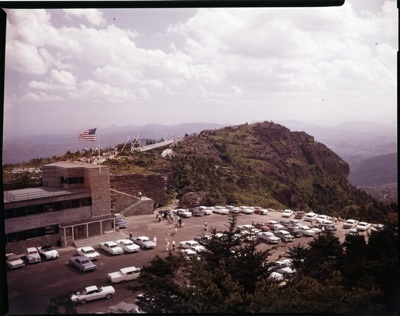

Hugh Morton realized the importance of imagery in promoting the state as a tourist destination, a fact reflected in his business dealings, his civic activities, and his photography. After inheriting Grandfather Mountain in 1952, Morton set about establishing an attraction that would become a cornerstone of the state's tourism industry. Focusing on the landscape, he used Grandfather Mountain's scenic advantages and wildlife to craft a destination for visitors seeking a connection with nature.

Building trails, interpretative centers, and the famous Mile-High Swinging Bridge, he made the Mountain a highly profitable attraction and one other tourist sites hope to emulate. Morton epitomized the tourism businessman, energetic, shrewd, and not afraid to stand up for his business interests. He fought the National Park Service over the route of the Blue Ridge Parkway in an effort to protect his investments at Grandfather Mountain.

Recognizing that resort destinations must constantly evolve in order to continue drawing visitors, Morton set out to preserve the image of Grandfather Mountain as an Appalachian haven, but also to give visitors fresh reasons to visit and, perhaps more importantly, to keep them coming back. The Highland Games, started in 1956, quickly became a colorful and popular celebration of Scottish culture that drew tourists from around the world. Other events such as the "Singing on the Mountain" drew more visitors to the mountains, and both Grandfather Mountain and state's tourism-related businesses reaped huge benefits. By selling the Mountain as a place where one could enjoy nature and culture, Morton created an image for his attraction that resonated well with visitors.

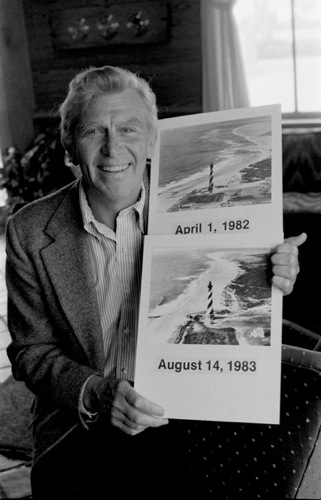

Morton's personal interest in tourism development led to his emergence as a leader in the state's tourism industry. Among the state's industries, tourism is a bit unique. Individual resorts and attractions compete with one another for tourist dollars, but they also collaborate on common advertising, and promotion. Morton and like-minded tourism business owners realized that all shared a vested interest in the creation and perpetuation of a distinct, appealing image of North Carolina. He led promotional groups such as Western North Carolina for Tomorrow and served on numerous state boards relating to tourism, including chairing the USS North Carolina Battleship Memorial Commission. In the 1980s he even spearheaded a move to save the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse from destruction by sea erosion, an effort motivated by both his personal love of the state's lighthouses as well as a desire to save one of the state's most important tourist icons. Recognizing the interdependent nature of tourism, Morton helped to forge bonds among the state's leading attractions and government agencies, helping to make tourism a powerful force in modern North Carolina.

By selling tourists the image of a state ready to entertain, enthrall, and serve, North Carolina public and private tourism promoters like Hugh Morton established the industry as one the state's most important. Today, the state's image as a leisure destination draws millions of visitors from across the country and around the world, creating jobs for thousands of North Carolinians. In 2008, travel and tourism contributed $22.2 billion in North Carolina's economy. And although the state offers more varied attractions than ever -- from a casino to exclusive beach resorts to ski slopes to national parks and parkways -- the importance of selling visitors a distinctive image remains an essential aspect of the state's tourism economy.