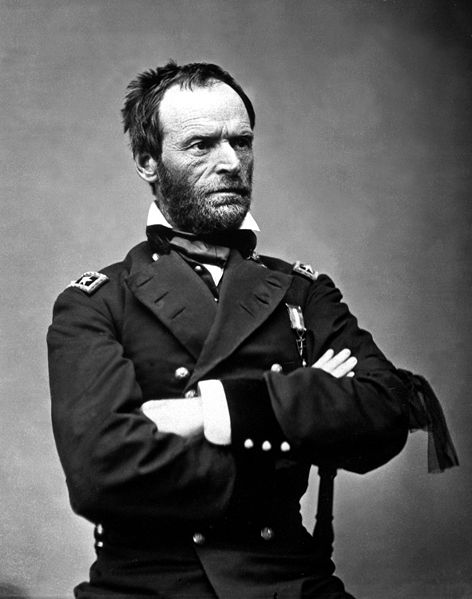

On December 21, 1864, Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman completed his March to the Sea by capturing Savannah, Georgia. Sherman's next move was to march northward through the Carolinas to Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederacy, where he would combine with the forces commanded by Union general-in-chief Ulysses S. Grant. The massive juggernaut under Grant and Sherman would ensure final victory for the Union by crushing Confederate general-in-chief Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Before marching to Richmond, however, Sherman would halt at Goldsboro, North Carolina, and unite with a Union force commanded by Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield.

Sherman began his Carolinas Campaign on February 1, 1865, by advancing into South Carolina. By February 17, his forces had captured Columbia, the capital of the Palmetto State. Thus far, the Confederates' resistance in South Carolina was ineffective. On February 22, Lee ordered Gen. Joseph E. Johnston to assume command of the forces opposing Sherman. During the first week of March, Johnston frantically concentrated his scattered forces in central North Carolina, while Sherman advanced into the Tar Heel State. On March 10, Confederate cavalry commander Wade Hampton surprised his Federal counterpart Judson Kilpatrick at Monroe's Crossroads in an engagement later dubbed "Kilpatrick's Shirttail Skedaddle." Although Kilpatrick quickly recovered from his shock and regained his camp, Hampton succeeded in opening the road to Fayetteville.

Meanwhile at Wyse Fork near Kinston, Confederate forces under Gen. Braxton Bragg attacked one of Schofield's two corps marching inland toward a junction with Sherman. Although the Confederates overran a portion of the Union line on March 8, the Federals succeeded in repulsing several Confederate assaults on March 10. On the night of the tenth, Bragg began withdrawing west toward Johnston.

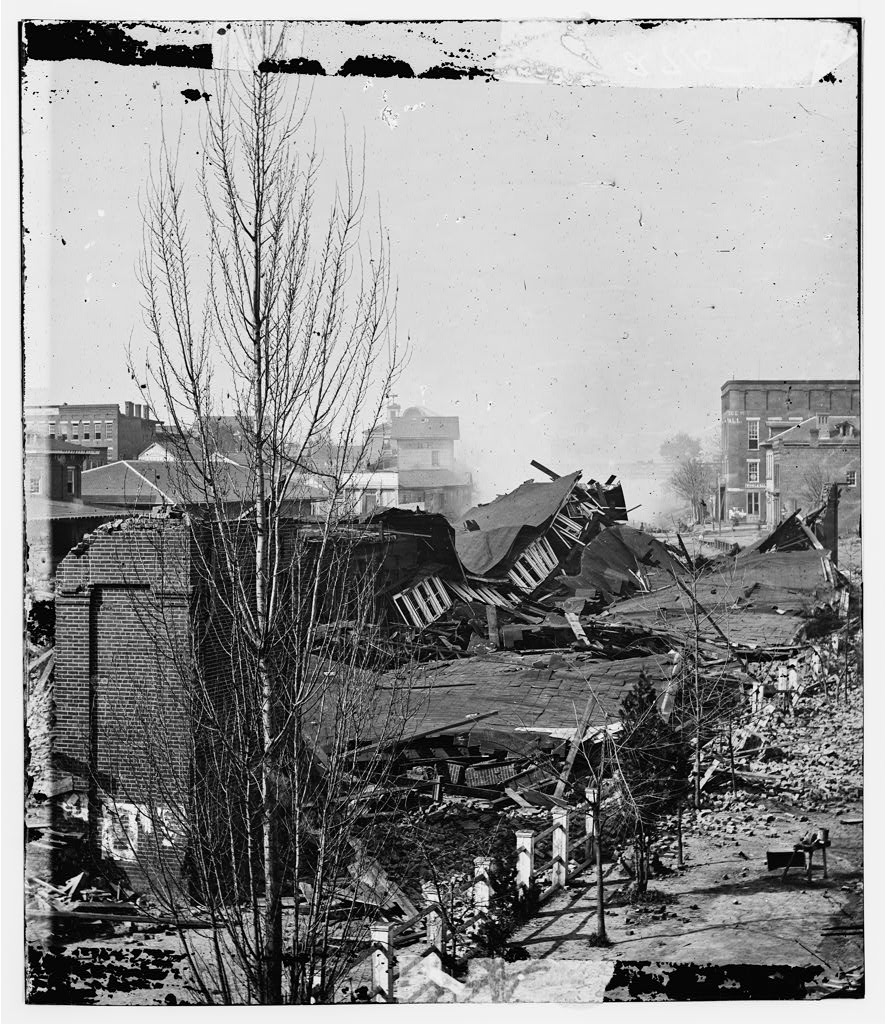

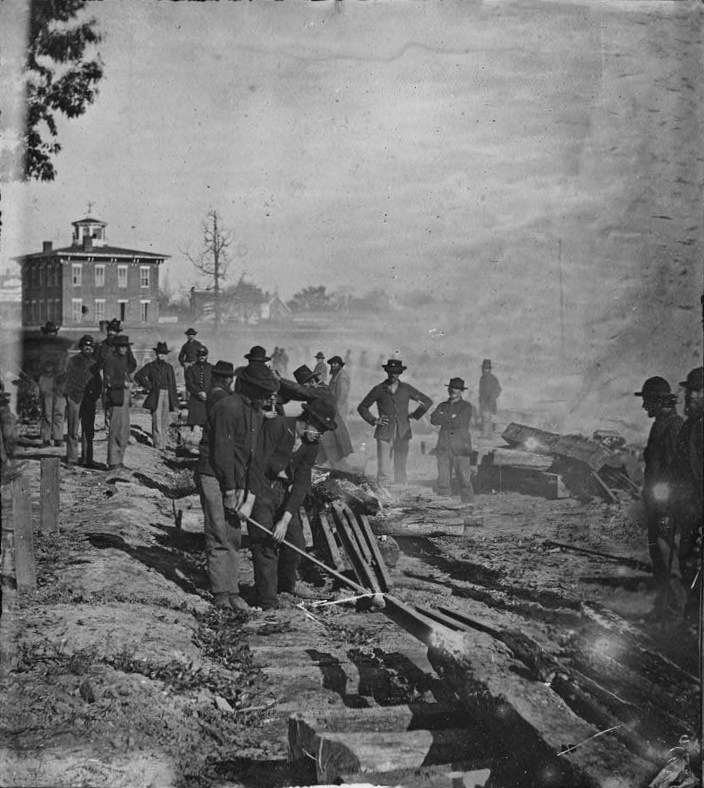

On March 11, Sherman occupied Fayetteville. During their four-day halt there, the Federals destroyed the former U.S. Arsenal. Sherman also plotted the final stage of his march to Goldsboro. His Left Wing would feint due north toward Raleigh, the state capital, while his Right Wing would march northeast toward Goldsboro. Johnston, meanwhile, gathered his forces at Smithfield because it was near the North Carolina Railroad and stood roughly midway between Raleigh and Goldsboro, Sherman's two most likely objectives.

On March 16, Confederate Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee fought a delaying action near Averasboro against Sherman's Left Wing, buying Johnston precious time to concentrate his forces around Smithfield. After the Battle of Averasboro, the Union Left Wing headed east toward Goldsboro. Acting on information provided by his cavalry commander, Wade Hampton, Johnston directed his Army of the South to concentrate at Bentonville and attack the Union Left Wing. On March 19, the first day of the Battle of Bentonville, the Confederates routed the lead Federal division, but the rest of the Left Wing dug in and, after a fierce struggle, the fighting ended in a draw. On the twentieth, the Federal Right Wing joined the Left Wing. Though outnumbered three-to-one, Johnston refused to withdraw and thus demoralize his troops. On March 21, a Union division launched an unauthorized attack against the weak Confederate left flank and nearly succeeded in cutting off Johnston's sole line of retreat. Only a desperate counterattack saved the Army of the South, which retreated toward Smithfield later that night. Content to let Johnston escape to Smithfield, Sherman reached Goldsboro on March 23 and formed a junction with Schofield.

On April 10, 1865, Sherman resumed his Carolinas Campaign. As the Federals advanced toward Raleigh, Johnston's newly renamed Army of Tennessee fell back and eventually halted around Greensboro. Meanwhile, the Union and Confederate commanders received word of Lee's surrender on April 9, convincing Johnston that further resistance was futile. On April 13, the Federals occupied Raleigh, and four days later, Sherman and Johnston began surrender negotiations at the Bennett Place near Durham. After President Andrew Johnson's rejection of Sherman's preliminary agreement, the two commanders met on April 26 and agreed to terms virtually identical to those Lee had received from Grant at Appomattox Court House. The resulting surrender was the largest of the war, embracing almost 90,000 Confederate troops in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida.

The Federals' march from Raleigh to Washington, D.C.

On April 30, 1865, Sherman's forces began their final march in their usual two-wing formation. Unlike their earlier marches, however, foraging was prohibited and the men carried only five rounds in their cartridge boxes instead of the usual forty. As the Federals toiled northward, the daily march increased until it reached almost thirty miles per day. Because of the springtime heat, many men straggled, some dropped from heat exhaustion, and a few unfortunates died. Rumor had it that the grueling pace resulted from a bet between some of Sherman's generals as to who would enter Richmond first. After marching through the battlefields of central Virginia, Sherman's troops arrived in Washington, D.C., and participated in the Grand Review on May 24.

Source Citation:

Gerrard, Phillip. "Sherman's Final March." Our State Magazine. Feb 06, 2015. Accessed May 3, 2022. https://www.ourstate.com/shermans-march/.