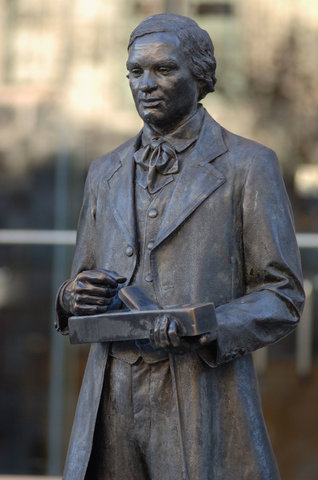

Thomas Day is North Carolina's most famous furniture craftsman and cabinetmaker. During his lifetime, his work was acclaimed from Georgia to Virginia, and he became one of the largest furniture manufacturers in North Carolina. In recognition of his talent, he was commissioned to furnish the interior woodwork in one of the original buildings of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His classically inspired furniture was built by hand and his wealthy clients included two North Carolina governors.

Born in 1801 in Dinwiddie County in southern Virginia, Thomas Day came from a fortunate family that had been free Black people for several generations. Thomas was educated by private tutors and apprenticed with his father John Day, Sr., who was a moderately successful cabinetmaker. The Day family moved to Warren County, North Carolina in 1817, because of increasing restrictions against free Black people in the early nineteenth century in Virginia. Fortunately for the Days, they moved just prior to a law forbidding relocation. In 1825, at the age of 24, Thomas moved to Milton in Caswell County, where he established a cabinetmaking business. The business quickly grew, and in 1827, he advertised "a handsome supply of mahogany, walnut and stained furniture" in the Milton Gazette and Roanoke Advertiser.

In antebellum North Carolina, many state laws and cultural norms restricted the activities of free Black people. However, Thomas Day achieved success both socially and professionally. He was highly admired and respected in his community of Milton and contributed to its prosperity. Despite his status as an enslaver, he challenged deeply entrenched racial and social injustices of the antebellum South. When he married a free Black woman, Aquilla Wilson of Virginia, Day confronted an 1826 law that barred free Black people from migrating to North Carolina. With the support of North Carolina's attorney general and more than 60 prominent white community members in Milton who petitioned the General Assembly on his behalf, Day and his wife were granted an exemption. Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Day were later accepted as members of the Milton Presbyterian Church. They worshiped with the white congregation in beautifully crafted pine, poplar, and walnut pews that Day had crafted.

By 1850, Thomas Day's furniture business was the largest of its kind in North Carolina. As his business thrived, he employed white apprentices seeking to break down racial barriers. He expanded his business to coincide with the growth and changing tastes of antebellum society. Day added his own stamp of creativity to a variety of styles including Federal, Gothic, Late Classical and Empire. His inventive decorative motifs and impeccable craftsmanship characterize his furniture, the quality of which eventually won him nationwide recognition. As the Civil War loomed in the late 1850s, North Carolina enacted more restrictive laws against Black business owners. Consequently, Day's business was quashed and went bankrupt before he died in 1860 or 1861.

The legacy of Thomas Day can be seen across North Carolina today. The North Carolina Museum of History exhibited their collection of his furniture in 1975 and again from 1996-1998. The Craftique Furniture Company in Alamance County has introduced a line of reproduction furniture featuring Day's designs. In 1975, Union Tavern, the site of Day's business from 1848 until his death, became a National Historic Landmark. The Thomas Day House and Union Tavern received a federal grant to restore the home and workshop in 2000. In response to the grant, North Carolina Senator John Edwards said, "Preserving the Thomas Day House will help future generations remember an important figure in the history of our state and nation."