1728–1796

Penelope Barker, revolutionary patriot, was born in Edenton, Chowan County. Her parents were Samuel Padgett, physician and planter, and Elizabeth. Penelope Barker's mother, Elizabeth Blount Padgett, was the daughter of John Blount and his wife and Elizabeth (Davis), and the granddaughter of prominent Chowan planter and political leader James Blount and his wife Anne (Willis).

Penelope had two sisters: Elizabeth, who married John Hodgson, a noted Edenton attorney; and Sarah, who married Joseph Eelbeck, a physician. While still in her teens, Penelope was shaken by a series of tragic blows. Within a year, death claimed her father and her sister Elizabeth. She quickly learned the meaning of responsibility, for the Hodgson household and Elizabeth's children, Isabella, John, and Robert, were placed in her care. In 1745, John Hodgson and Penelope Padgett were married. Two sons, Samuel (1746–55) and Thomas (1747–72), were born of this union. The marriage was a short one, however, for in 1747, Hodgson died.

Again Penelope was forced to assume heavy burdens: the care of five children and the management of the Hodgson plantations. A most eligible widow at nineteen, she soon attracted the attention of James Craven, local planter and political leader, and they were married in 1751. While no children were born of this union, the marriage did result in a sizable increase in Penelope's wealth. When Craven died in 1755, his extensive estate passed entirely into her hands.

Penelope was only twenty-seven when James Craven died, and her beauty, coupled with her great wealth, attracted many suitors. One of the most prominent of these was widower Thomas Barker (1713–89), Edenton attorney and member of the assembly, who married Penelope in 1757. Three children were born to the Barkers, none of whom lived to reach the age of one year: little Penelope survived less than two months, Thomas less than nine, and Nathaniel less than ten. In 1761, Penelope was left to manage the household and plantations alone, for in that year Thomas Barker sailed for London to serve as agent for the North Carolina colony. As a result of the American Revolution and the British blockade of American ports, he was forced to remain in England until early September 1778.

In contrast to most colonial wives, Penelope Barker was well accustomed to single-handedly managing her household and lands. Her character had been tempered by tragedy. She had borne five children and mothered her husbands' four others by previous marriages. By 1761 seven of these children had died, and in 1772 her son Thomas Hodgson died at the early age of twenty-five. The lone surviving child, Betsy Barker, also left Penelope's care through marriage to Colonel William Tunstall, a prominent planter of Pittsylvania County, Va.

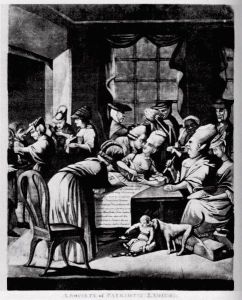

As the colonial independence movement grew in intensity, with an increase in riots and other extralegal activities in opposition to British taxation, Penelope, because of her husband's position, probably realized as much as any other person in North Carolina the potential costs of such actions. Thus, her leadership of fifty-one Edenton women, on 25 Oct. 1774, in open opposition to Parliament's Tea Act of 1773 must have been well considered. The choice of a tea party as the form for such an action is not surprising. The tea party was in the colonies, as in Britain, the most socially acceptable of gatherings, often including both men and women. Meeting at the home of Elizabeth King, wife of an Edenton merchant, with Penelope Barker presiding, the ladies signed the following resolve: "We the Ladyes of Edenton, do hereby solemnly engage not to conform to ye pernicious Custom of Drinking Tea, or that we, the aforesaid Ladyes, will not promote ye wear of any manufacture from England, until such time that all Acts which tend to enslave this our Native Country shall be repealed." This episode might well have passed unnoticed by history if a caricature depicting the "Edenton Tea Party" had not appeared in the Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser on 16 Jan. 1775.

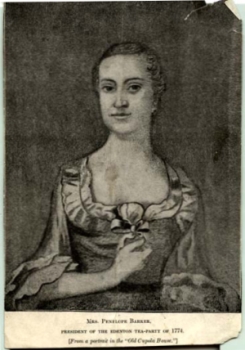

Following the Revolution, Penelope led a more subdued life in Edenton, finally welcoming the return of her husband in 1778 and mourning his passing in 1789. She outlived Barker another seven years and in 1796 was buried beside him in the Johnston family graveyard at Hayes Plantation, near Edenton. The only known portrait of Penelope Barker hangs in the Cupola House, Edenton.