1713–89

Thomas Barker, lawyer and political leader, was born in the colony of Rhode Island. Little is known of his ancestry or life before he moved to North Carolina. He received legal training in Rhode Island, and, before immigrating to North Carolina, he was associated with a Boston mercantile house. Arthur Dobbs, royal governor of North Carolina from 1754 to 1765, stated that Barker came to the colony "as the skipper of a New England bark." In all probability, Barker was serving as the on-board factor for a New England commercial firm, sailing with a cargo to supervise its sale and to oversee the purchase of goods for the firm.

Barker arrived in Edenton in 1735 and immediately entered upon a career in public service. In September 1736 he received an appointment as clerk to the lower house committees on Grievance and Propositions and on Public Claims. In April 1741 he secured from Governor Gabriel Johnston a six-hundred-acre land grant in Bertie County and soon thereafter crossed the Roanoke River from Edenton to take possession of this land. Early in 1742, having settled his plantation, he married Pheribee Pugh (née Savage), widow of Francis Pugh, wealthy planter, shipowner, and member of the governor's council. To this marriage one daughter, Betsy, was born.

In March 1742, Barker was elected a member of the assembly from Bertie County. Early recognized for his legal and business abilities, he was chosen to draft bills regulating the colony's general and county courts and to be a member of the Committee on Public Accounts. Reelected in 1746, he was chosen as a commissioner to revise and print the laws of the province. With the creation of the position of public treasurer for the northern district in 1748, Barker was selected to fill the post. He held this office until 1764.

During the representation controversy arising over Governor Johnston's efforts to break the northern counties' control of the assembly, Barker served as the agent for the northern counties in their appeal to the board of trade. Early in the 1750s, following his wife's death, he reestablished his residence in Edenton and was elected as that borough's representative to the assembly in 1754, beginning almost a decade of continuous service in the lower house. As during his earlier tenure there, his main efforts were directed toward financial and judicial reform. He was a constant member of the joint assembly-council committee that examined the accounts of the colony's treasurers. He tackled the thorny problem of North Carolina's court system by submitting bills to establish supreme, superior, and inferior courts; to define the duties of the chief justice and attorney general; to expand the right of jury trial; and to regulate the fees assessed by the courts. As a staunch supporter of the Church of England, he authored bills calling for the establishment and support of new vestries. His devotion to his constituents in Edenton was evidenced by his bills to improve the inspection of exports at the port, to confirm existing land patents in the area, to repair the county's courthouse, and to erect St. Paul's Church in the parish. Barker's high standing in the assembly is best shown by his repeated selection to chair the committee of the whole and by his appointment as a member of the Committee of Correspondence in December 1758.

Barker's prominence among assembly leaders singled him out for criticism by the royal governor when the latter and the assembly were at cross purposes. Such was the case from 1757 through 1760, during the struggle over the emission of paper money and payment of the governor's salary. In various letters to the board of trade, Governor Arthur Dobbs accused Barker of bribery, election fraud, and misuse of provincial funds to continue the power of the opposition clique in the assembly. These charges were directed more against a faction of the assembly than against Barker personally, for in 1757 Dobbs recommended him to the board of trade for membership on the council, stating that Barker had "promoted His Majesty's interest in the Assembly."

By the late 1750s, Barker had established himself as a successful attorney in Edenton and a political leader of prominence throughout the colony. In Edenton, a thriving commercial center during the 1750s, Barker met and was attracted to Penelope Craven, a widow since 1755. In 1757 they were married. Of the three children born of this marriage, none survived to reach the age of one year. The grief over these losses was softened somewhat by the happy marriage of Betsy, Barker's daughter by previous marriage, to Colonel William Tunstall, a wealthy planter of Pittsylvania County, Virginia.

In the early 1760s a controversy erupted between the assembly and Governor Dobbs over the selection of an agent to represent the colony in London. Barker was the overwhelming choice of the lower house, while the governor and council countered with Samuel Smith. Efforts at compromise proved futile. The council refused to approve Barker as agent, and the assembly blocked all appropriations for Smith's salary. Thus, in 1761, both men sailed for London—Smith to represent the council and Barker the assembly. Once in London, Barker appears to have served as an aide to James Abercromby, who had held the North Carolina agency since 1749. Barker is not recorded as having appeared before the board of trade until after Abercromby's death in 1775. The period must have proved a trying one for Barker, separated from his wife and friends in a strange land.

No record exists of Barker's work and life in London prior to 1774. In that year, however, he was officially appointed as special agent, with Alexander Elmsley, to represent North Carolina in the court and attachment controversy before the board of trade. He submitted a memorial to the board on this subject in March 1775 and attended sessions of the body during May of that year, when the memorial was discussed. As the Anglo-American problems deepened and the movement toward open colonial rebellion accelerated, Barker's role in London became increasingly more difficult, just as his concern for his wife and friends in North Carolina grew more acute. In June 1775, Barker and Elmsley achieved for North Carolina an exemption from the Trade Restraining Act, which had been passed by Parliament two months earlier. However, news of this exemption was received with hostility by North Carolinians, who had forced the flight of Governor Josiah Martin and who had recently heard of the opening skirmish of the Revolution at Lexington and Concord. No doubt disillusioned by the totally unexpected, bitter denunciations of his efforts and deeply concerned about his wife's welfare, Barker in 1776 wanted only to return to America. However, the outbreak of open warfare in the colonies and the British blockade of America made his immediate return impossible. In late spring of 1778, he was able to leave England for France and on 8 July sailed from Nantes for North Carolina.

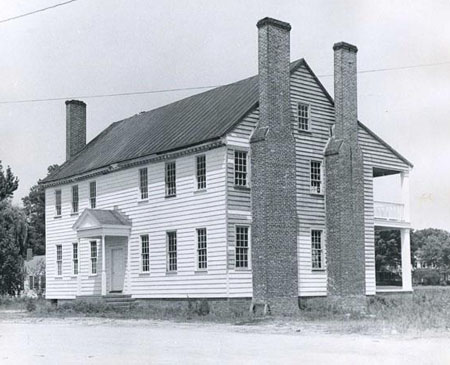

Early in September 1778, Barker arrived in Edenton and was reunited with his wife after a separation of seventeen years. However, because of his prolonged absence from the state, he was not considered a North Carolina citizen. If judged a Loyalist, he would forfeit his property to the state; he moved quickly to avert this possibility and took the prescribed oath of allegiance before an Edenton justice of the peace on the day following his return. On 20 Jan. 1779, the grant of citizenship was formalized by act of the state senate. The following month, Barker was nominated in the General Assembly as a delegate to the Continental Congress. While he did not win election, his nomination reveals that he was still held in high esteem. Following his return to Edenton, Barker, sixty-five years old, retired from public service to enjoy the comforts of his home and friends. At his death, he was buried in the Johnston family graveyard on the grounds of Hayes Plantation, near Edenton. The only known portrait of Thomas Barker, an oil attributed to Sir Joshua Reynolds, was painted in about 1771 while Barker was living in London and is part of the Hayes collection at Hayes Plantation.