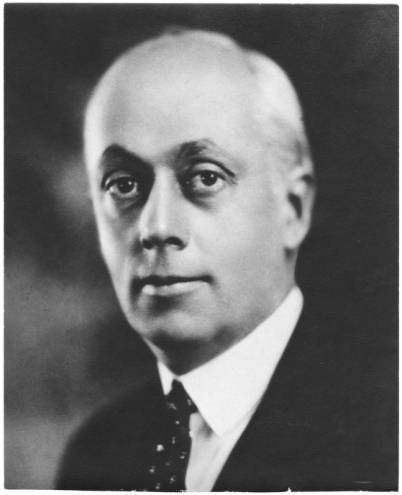

11 Apr. 1883–20 Apr. 1955

Harry Woodburn Chase, university president, was born in Groveland, Mass., the son of Charles Merrill and Agnes Woodburn Chase. In 1900 he entered Dartmouth College, from which he received the A.B. degree, magna cum laude, in 1904. A Rufus Choate Scholar during his junior and senior years, he received special honors in French and philosophy and was ranked fourth in his class. He was admitted to Phi Beta Kappa and was a commencement speaker at his graduation.

Chase began his professional career in education in 1904 as a high school teacher. In 1908 he received his master's degree from Dartmouth, with a thesis entitled "Plato's Theory of Education." Not content with this preparation, he relinquished his position that year and entered the new, nationally acclaimed Clark University at Worcester, to study under Dr. G. Stanley Hall. He held a fellowship in psychology and served as the director of the clinic for subnormal children in 1909–10. He later translated and published the series of lectures delivered at Clark by Sigmund Freud, which influenced the development of psychoanalysis in the United States. Chase received the Ph.D. degree from Clark in 1910.

In September 1910, Chase became a member of the faculty of the department of education at The University of North Carolina. In 1914 he became professor of psychology and began to introduce laboratory courses and scientific methods in this new and expanding field. At the university, he served on various faculty committees and was chairman of the Committee on Intellectual Life. He was also appointed acting dean of the College of Liberal Arts, following the death of E. K. Graham in October 1918, and chairman of the faculty after the death of Marvin H. Stacy in January the following year. In June 1919 he was elected president of the university.

In December 1910, Chase married Lucetta Crum, a native of Indiana and a graduate of Coe College. She had been a graduate student at Clark University and had received the M.A. degree in 1910. Although Chase was a native New Englander, he quickly adapted himself to the environment of North Carolina and identified himself completely with the interests of the university. During the eleven years of his presidency, he devoted his attention to objectives including the establishment of the office of dean of students and the transfer of the responsibility of supervising student discipline under the honor system from the office of the dean of the College of Liberal Arts to a committee of the faculty and the student council. The entire administrative structure of the university was entirely reorganized through the provision of administrative boards to formulate policies and advise the deans and officers of the principal units. William M. Kendal of the New York firm of McKim, Mead and White was appointed consulting architect to develop plans for the expansion of the physical plant by the addition of twenty-one new buildings and very extensive modification of three others, to accommodate a student body of 3,000. The faculty was increased from 78 to 115 members, and the annual support of the university from $270,097 in 1918–19 to $1,342,974 in 1928–29. There was a new emphasis on staffing the professional schools with faculty trained and experienced in professional education and administration instead of professional practice and on adopting national, to replace state and regional, standards of scholarship and attainment. The Graduate School was thoroughly reorganized for training teachers and professional experts, and a strong central library was built up for the support of research. The university defended academic freedom and the right to teach science against the nationwide fundamentalist crusade to outlaw the teaching of evolution; established new departments of dramatic art, music, journalism, psychology, and sociology and new schools of business administration, public welfare, and library science; and strengthened and enriched both the widely known Institute for Research in Social Science and The University of North Carolina Press.

Chase's decision to appoint a dean of students grew out of the confusion that resulted from the control of the students during World War I by military officers. Student morale greatly declined, and Chase found it necessary to place policy-making, curriculum management, and student conduct control under two full-time officers.

Another matter that severely challenged his leadership was that of establishing the principle of staffing professional schools with faculty members not only professionally trained but also experienced in professional teaching and administration. The test came in 1923 in the appointment of a dean at the Law School. The majority of the trustees were lawyers who thought the position should be filled by a distinguished attorney. Chase contended that the point of view held by the trustees was outmoded and insisted that training in law school administration was fundamental to the successful development of the best type of legal education. Merely practicing law did not provide the experience required in order to give legal training. Chase succeeded in establishing this principle throughout the university.

The establishment of the department of sociology and the encouragement of the Institute for Research in Social Science likewise called for long and diplomatic handling. Sociology was generally suspect in the South, not so much by churchmen as by industrialists and politicians, who saw sociology and socialism as related and horrendous subjects. Having secured the acceptance of a sociology department in principle, Chase appointed H. W. Odum, a native southerner who had trained with Chase at Clark and who was then serving as dean of the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Georgia.

The most difficult of Chase's objectives was freedom to teach and publish, the fight for which lasted through several years and two 1920s assemblies of the legislature and of the Synod of the North Carolina Presbyterian Church. In defeating those who opposed the teaching of evolution in the university, Chase added to skill in presenting convincing arguments the support of several strong leaders of other churches and colleges in the state and of alumni and students. The margin of victory in both legislative contests was reasonably large and very gratifying.

During his stay in North Carolina, Chase held posts in the North Carolina College Conference, the Southern Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools, the National Association of State Universities, the National Education Association, and the American Association of Adult Education. He also served as a member of the boards of several educational foundations, including the General Education Board and the Julius Rosenwald Fund.

Chase left Chapel Hill in 1930 and became president of the University of Illinois in July of that year. He reorganized Illinois's administrative structure in very much the same manner as North Carolina's, establishing a number of new departments and schools. In 1933 he accepted appointment as chancellor of New York University and once again began a program of administrative reorganization and expansion.

Following his retirement in 1951 Chancellor and Mrs. Chase spent summers at their cottage at North Port, Long Island, and winters at Sarasota, Fla. He was at his Florida home when he died. He was survived by: his wife, Lucetta C. Chase; a daughter, Elizabeth Woodburn Chase, who married Marion Foy Stone in 1933; an adopted son, Carl; and a grandson, Harry Stone. Chase was an Episcopalian and a Democrat. The University of North Carolina has two portraits of him.