16 Aug. 1858–26 Dec. 1940

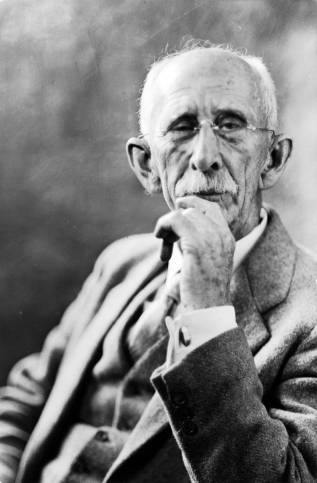

Henry Horace Williams, philosopher, was head of the Department of Philosophy at The University of North Carolina for all but the last five emeritus years of the fifty he taught there. Born in the isolation of Gates County, on the edge of the Dismal Swamp, he was the eldest of eight children of a country doctor, Elisha, and his second wife, Mary Taylor Williams. A life of teaching in an epochal period brought him into prominence. As teacher he inaugurated the department and became its first Kenan Professor. As philosopher he managed to convey the current and complex ideas of idealism, particularly Hegelian dialectic, with a mastery that prompted his most famous student, Thomas Wolfe, to call him the "Hegel of the Cottonpatch." As a person he had wide impact. He continued to be talked about in legislative halls as well as at dinner tables. In June 1968 he was the subject of the Reader's Digest series, "My Most Unforgettable Character," by Dr. O. B. Ross, Sr.

From farm boy on poor land devastated by the Civil War to Heidelberg, Germany, getting educated was difficult for him. After brief but crucial preparation and an interval of clerking, he entered the state university in 1879. Admission was a feat hardly more difficult than the trip to reach Chapel Hill through winter floods by muledrawn cart, train, and stagecoach. There he distinguished himself in ancient languages, moral philosophy, and mathematics and was active in the Philanthropic Society, one of the two debating societies that in those days governed the campus life and the honor system. As a senior he read German and Greek intensively and in 1883 was granted an M.A., the first advanced degree ever to be awarded for achievement rather than honor, as well as the B.A. degree. President of his senior class and winner of three medals, he became engaged to a lady considered by his college mate and biographer Robert Winston to be one of the most eligible in the village, although marriage did not then follow. In 1891 he was married by Bishop Phillips Brooks at the home of C. J. Havemeyer, the "sugar king," at Yonkers-on-the-Hudson to Bertha Colton of Middletown, Conn., the daughter of an Episcopal minister.

Williams studied further at the Yale Divinity School (B.D. 1888) and won a fellowship at Harvard. There were teaching posts and study in Germany. The most influential teachers were Timothy Dwight at Yale and Dean Edward Everett, William James, and Josiah Royce at Harvard, where Williams's independent mind was stimulated by Hegel's works and the literature of the religions of the world just coming from the East. Both permeated his teaching and writing, particularly logic, ethics, and history. His use of the dialectic, with force of drama that every successful teacher employs, is typified in his summary: " . . . the schools were like departments. Each stood for something definite and true. Spinoza had explored the absolute. He found no place for the individual. Kant had explored the individual. He found no place for the absolute. Science had explored nature. It found no place for the absolute or the individual. Then philosophy will be the synthesis of Spinoza, Kant and science. This is the system of Hegel."

Acceptance of the post at The University of North Carolina was his deliberate choice to help liberalize the institution intellectually and thus free the state and the South from the grip of orthodoxy. Williams proved equal to the task from the first, agreeing that he would teach Christian philosophy if the professor of mathematics would teach Christian math. Long before it became a civil rights issue he declared that all persons have equal rights to opportunities. His classes were well attended, and no leader on campus could afford to miss studying under him. Yet he said in his autobiography, The Education of Horace Williams (1936), that for twenty-five years he did not know whether his official life would last until commencement. Popular with students and active on the faculty, he championed the honor system. He ferreted out violations of training rules by football team members while chairman of the athletic committee, and at the suggestion of two students he helped form an honorary society, Golden Fleece—for senior men as it turned out, though not for Williams: exclusion of women was one of his rare failures. On appeal from an editor of the Tar Heel for advice when the university president ordered him to submit editorials for approval before publication, Williams demurred from giving advice but said that he himself would write his own editorials and invite the president to write any he wished if he would agree to sign them.

His ability to find and hold his students was based on genuine interest in them as well as in philosophy. He learned to master those educational techniques universally admired: thorough preparation of lectures, wide knowledge of subject, wit, involvement of students in discussion, strong and continuous personal contacts, and pretesting of ideas. Subjects were abstract but illustrations homely; problem-solving and formulation of realizable goals were encouraged. His own involvement in campus ethical and political issues was honest and courageous, which attracted hostility as well as admiration. The teaching of evolution was not banned as elsewhere; in his words, "There were no heresy trials."

His first book was Evolution of Logic (1925) and his major work was Modern Logic (1927). Style, form, and substance were Hegelian, which as a discipline had by then a strong adversary in pragmatism. Preferring a holistic approach, Williams countered this and other trends towards fragmentation. No less an activist, he concentrated on training leaders, rather than professionals, for free and rounded development of individuals and institutions in the South. His students formed a school of "Horatians" which did in fact dominate and direct social change in church, school, and courts to such an extent that it is credited with having "broken the fetters of a beautiful casteridden past" (Horace Williams: Gadfly of Chapel Hill, Robert W. Winston, 1942 [portraits], p. 299). Horatians organized the Horace Williams Philosophical Society in 1943 and formed local philosophical discussion groups. In Charlotte one survived, but most declined as did the St. Louis School and American Hegelianism generally, due as much to the dispersal of philosophers into other fields as to the competition of other theories. The Horace Williams Philosophical Society issued two publications, Logic for Living: Dialogues from the Classroom of Horace Williams, edited by Jane R. Hammer (1951 [portrait]), and Origin of Belief, by Williams (posthumous, 1978 [portrait]).

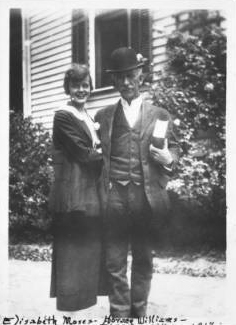

After the death of his wife in 1922, he adopted Miriam Young Bonner, a young teacher at a nearby college. Following a trip to England and a few months at home in Chapel Hill, Miss Bonner accepted teaching posts in various cities in the East and in California, where she married. Williams gave all of his property to The University of North Carolina in trust, the income to be used for fellowships in philosophy. He died at age eighty-two and was buried in the Old Chapel Hill Cemetery.