See also: Desertion, Civil War; World War II.

Conscription of male citizens to supply North Carolina's military forces began early in the colonial era. Enacted first as a frontier necessity, the principle of universal service became enshrined in American tradition. Prior to the Civil War a weak central government relied on the states for soldiers. Despite national conscription laws in both North and South during the Civil War, the federal government did not assume total control over the nation's military until the twentieth century. Conscription played a large role in America's transformation into a global superpower, but the bitter legacy of the Vietnam War effectively ended the draft.

The earliest written authority for conscription appeared in the Carolina charter, issued to the Lords Proprietors by Charles II in 1663. The charter empowered the Proprietors to "levy, muster, and train up all sorts of men . . . and to make war." The near catastrophe of the Tuscarora War (1711-13) resulted in the Militia Act of 1715 establishing the principle of universal service for all "freemen" between the ages of 16 and 60. The act remained largely unchanged during the colonial period, although additional measures were occasionally required. Between 1712 and 1776, when North Carolina enjoyed a period of extended peace, broken only by the French and Indian War and the Regulator uprising, militia service was sometimes neglected.

After the Declaration of Independence in 1776, the new state of North Carolina reorganized the militia system enacted under British rule. Throughout the Revolution the state militia remained separate from the standing army of the Continental Line. A growing list of exemptions spared many citizens from service, and those not exempted could hire a substitute or pay a commutation fee. Following the war and a period of relative tranquility, North Carolina sent 14,000 troops, about half of them conscripted, to fight in the War of 1812. Although the militia was not directly involved in the regulation of enslaved people, it did mobilize during uprisings of enslaved people, such as the Nat Turner Rebellion of 1831.

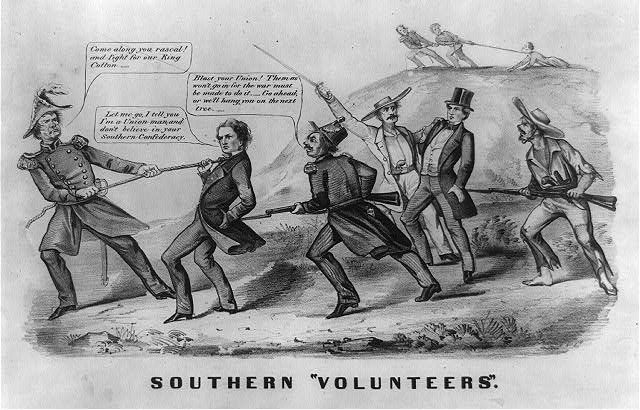

The secession of the Lower South in 1860-61 placed North Carolina in a precarious situation; despite strong Unionist sentiment, the state felt close ties to other enslaving states. Anticipating the need for defense in the spring of 1861, the General Assembly strengthened the militia law to include all white males between the ages of 18 and 45, except members of the clergy. It further provided for the creation of volunteer companies. Volunteers, expecting quick victory and martial glory, fought the first battles of the Civil War.

By the spring of 1862 the Confederate army faced a probable shortage of troops, and on 16 April the Confederate Congress enacted the first national draft law in American history; the North did not implement a full-scale draft until 1863. The sweeping legislation extended the service of all volunteers for three more years and enrolled all white males between 18 and 35 into the Confederate army. Measures in August and October 1862 increased the ages of eligible men to 45 but added further exemptions.

Conscription only delayed defeat, as dissatisfaction with the Confederacy grew and the Rebel grasp slipped from the southern states. North Carolina, bearing an increasing brunt of the demand for men and materiel, supplied the Confederacy with the highest number of troops and lost the largest number to battlefield death and disease; it also led the new nation with nearly 25,000 deserters, feeding the political war in Unionist counties. Confederate conscription ultimately failed for a number of reasons, including the military's poor control of the system, the attempt to bypass the authority of the states, and the uneven application of the law.

A period of prosperity and peace, briefly interrupted by the Spanish-American War in 1898, followed, and conscription gradually became a national prerogative. In 1873 Congress reiterated the principle of universal service, declaring that every male citizen between 18 and 45 (with several exceptions) was eligible for militia duty in his home state. In 1903 Congress renamed the militia the National Guard and created a separate state Reserve system.

On 18 May 1917, five weeks after declaring war on Germany, President Woodrow Wilson signed into law the Selective Draft Act. The act established the most comprehensive national conscription system to date, with a national organization and more than 4,650 civilian local draft, appeal, and advisory boards. In North Carolina, as in other states, the governor administered the draft through the office of the state adjutant general. Nearly 87,000 North Carolinians served in the military during World War I.

The onset of World War II in Europe and Asia shook America from its isolationism and consequent military weakness. In 1940, at the urging of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Congress instituted the first peacetime draft in U.S. history. North Carolina members of Congress voted unanimously for the Burke-Wadsworth Bill, signed into law on 16 September as the Selective Service and Training Act of 1940. (North Carolina led the nation in the rate of volunteerism during the six-month period prior to enactment of the law.)

During World War II more than 1.1 million men appeared before the state draft boards. Almost 370,000 North Carolinians served in the military, about two-thirds through conscription; another 1,000-plus North Carolina women served voluntarily. High rejection rates-up to 50 percent in some areas-revealed poor health and educational conditions in the state.

Conscription ended in 1947, only to be reinstated by Congress two years later with the onset of the Cold War. North Carolina sent 177,461 men into the military during the Korean War, although the percentage conscripted is unknown. Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, volunteerism remained high and inductions low, but the demand for manpower exceeded the number of volunteers as U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia increased. The Vietnam War proved increasingly unpopular among a large portion of the populace, especially with younger people who faced conscription. About 216,000 North Carolina citizens served in the military during the Vietnam era, but a relatively small fraction saw actual combat.

Conscription was discontinued in 1973 with the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam, and the state office of Selective Service closed in 1976. Thereafter America relied on an all-volunteer military, though a debate raged in the early 2000s over whether to reinstate the draft.