See also: Eugenics; Eugenics legislation in North Carolina

The North Carolina Eugenics Board, operating under the theories of the science of eugenics, or racial improvement through selective breeding, began its work in 1933 after the General Assembly passed a sterilization law. The new ordinance replaced a 1929 statute that had been declared unconstitutional. North Carolina was one of several states that created eugenics boards in the 1930s. Between 1929 and 1974, the North Carolina Eugenics Board approved the sterilization of more than 7,600 people, the third-highest figure in the nation behind California and Virginia. The vast majority of individuals sterilized were women who had been diagnosed as "feeble-minded" by various tests.

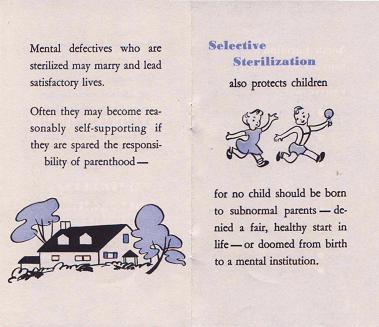

In 1883 English scientist Sir Frances Galton, a cousin of Charles Darwin, had proposed the science of eugenics, believing that humankind could only reach its full potential by increasing breeding among "desirable stock" and decreasing breeding among "undesirable stock." Sterilization was one of the methods adopted to restrict the increase of undesirable human beings. Many welfare proponents and lawmakers regarded sterilization as an acceptable solution in eliminating poverty and mental defectiveness.

The North Carolina Eugenics Board was composed of five members of state government: the commissioner of public welfare, the secretary of the state board of health, the chief medical officer of the state hospital at Raleigh (Dorothea Dix Hospital), the chief medical officer of a state mental institution outside Raleigh (this position rotated among the different institutions), and the attorney general. Well into the 1950s, white women comprised over three-fourths of those sterilized. This one-sided representation was probably because few African Americans received early welfare assistance and they remained unidentified. In addition, many of those sterilized were inmates of state mental institutions, and of the ten state-operated institutions, only three housed black inmates. When welfare benefits became available to minorities, the number of sterilizations performed on them increased.

Since the eugenics programs only touched people with little public influence, there was almost no local or national opposition to sterilization. Not until eugenics programs came under fire from civil rights and women's rights groups in the 1960s and 1970s did states discontinue sterilization and dissolve the boards. The North Carolina Eugenics Board, which had been one of the most active, was abolished in 1977.

In 2003 a movement to compensate those who had been sterilized began to gain strength in North Carolina. That April Governor Michael Easley-influenced greatly by "Against Their Will: North Carolina's Sterilization Program," a 2002 investigative series in the Winston-Salem Journal chronicling the history and effects of the state's eugenics program-officially apologized on behalf of the state government, appointed a Eugenics Study Committee, and signed legislation that removed all laws that sanctioned involuntary sterilization. Easley and the committee subsequently proposed granting sterilization victims, at state expense, a variety of benefits, including educational support, counseling, health care, and cash payments. The issue of reparations remained controversial, however. In April 2005 Forsyth County representative Larry Womble submitted legislation to the General Assembly that would set payment at $20,000 for every individual victimized by the state's eugenics program, but its future passage was unclear. Approximately 3,400 victims of sterilization were believed to still be alive as of 2005.