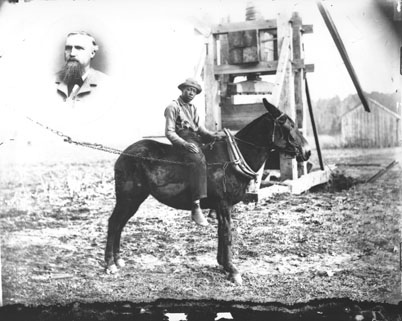

Mules were common features of the North Carolina landscape until the mid-twentieth century. From a census number of 125,608 in 1940, mules have declined so precipitously in the state-beaten out by mechanized farming and in many cases sold for dog food-that even to see one in the early 2000s may require a trip to the town of Benson's annual Mule Day festival or to a place of amusement such as the E-Z Ride Ass and Mule Farm near Liberty.

The mule's ancestry is specified in its taxonomical designation, Equus caballus x asinus, a creature born of a mare and sired by a jackass (in the rare cases in which the female parent is the donkey, the offspring is called a "henny"). Its tenure in the United States is almost coextensive with the Republic itself: George Washington founded the American line, breeding his Virginia mares to a jack named Royal Gift, a present from the King of Spain, as early as the 1780s. Washington, an astute and innovative farmer, foresaw an almost infinite expansion of agriculture in the new nation and recognized the appropriateness of the mule's many virtues to that awesome demand.

Mules, as the future president discovered, possess wonderful stamina and can easily work 12 hours a day on just over half the rations demanded by a horse. Their dietary needs can be met with cracked corn supplemented by browse of the animal's own choice-a choice famously unfinicky, as the phrase "grinning like a mule eating briars" acknowledges. Mules are steady, sure-footed, and cautious, able to walk between rows without trampling crops and to negotiate treacherous terrain without much danger of disabling injury-even at night, when serving as the coon hunter's mount as he follows the hounds through woods and across streams. Mules are extremely hardy and disease resistant (a proverb in the British army declares that "one never sees a dead mule") and considerably longer lived than the average horse (a mule in Vance County attained a documented age of 50 years).

Along with these virtues come some problematic qualities. An annoyed mule will kick with deadly force, and mules seem to nourish grudges. As William Faulkner observed, a mule will work for you for many years for the opportunity to kick you just once, and it is wisely stated that if you have anything to say to a mule you had better say it to his face. There is a folk tradition that a mule will willingly follow a white horse; but the truth is that he will follow anything if he wants to and nothing if he does not. Among the many stories of the stubbornness of mules is an anecdote about a man who, infuriated by his mule's refusal to pull an overloaded wagon, built a fire under the animal in order to make it move, whereupon the mule simply took a few steps forward to position the wagon over the fire.

Such stories abound in southern literature, wherein mules both living and dead make numerous appearances. Among North Carolina writers who have dealt with mules in fiction are Doris Betts, Clyde Edgerton, Kaye Gibbons, Bernice Kelly Harris, Ovid Pierce, Flora Ann Scearce, and Thomas Wolfe. North Carolina oral tradition is also rich in mule material. Such literary and subliterary matter formed the theme of the Dead Mule Club, a restaurant and bar in Chapel Hill whose walls boasted mule-related artifacts of various kinds, including an authentic mule skull above the fireplace.