See also: Griffith Rutherford (biographical entry)

Rutherford's Campaign was North Carolina's contribution to a multistate military effort, planned early in the Revolutionary War, to break the power of the Cherokee before they could combine with the British against the rebels. Cherokee leaders such as Dragging Canoe saw the outbreak of the Revolution as a chance to reclaim lands taken by the settlers of the Carolinas and Georgia. British-American Indian diplomatic agents John Stuart and Alexander Cameron, interested in gaining full advantage from the Cherokee force in the fight against the American independence movement, tried unsuccessfully to prevent the Cherokee from going to war until they could coordinate their attacks with the arrival of regular British forces. Between April and July 1776, several dozen frontier settlers were killed; hundreds were besieged in frontier forts, and Cherokee raiders reached the western banks of the Catawba River across from Mecklenburg County.

Brig. Gen. Griffith Rutherford, commander of the militia in the Salisbury District, wrote the North Carolina Council of Safety on 5 June 1776 for permission to strike deep into Cherokee territory. He also proposed that South Carolina and Virginia participate in the attack. At the same time, unknown to Rutherford, Gen. Charles Lee, commander of the Continental troops in the South, and John Rutledge, president of the South Carolina Council of Safety, were asking North Carolina and Virginia to join such a campaign.

North Carolina's forces, under Rutherford, were to besiege the Middle and Valley Cherokee towns in western North Carolina, while forces from other states would assault the Cherokees in other areas. Despite consenting to the ambitious plans, the three state governments could not launch their attacks at the same time. Communication between each state was slow, and the need for action compelled each one to strike as soon as their troops were assembled. South Carolina moved first, sending 1,100 men under Col. Andrew Williamson against the Lower Cherokee towns at the end of July.

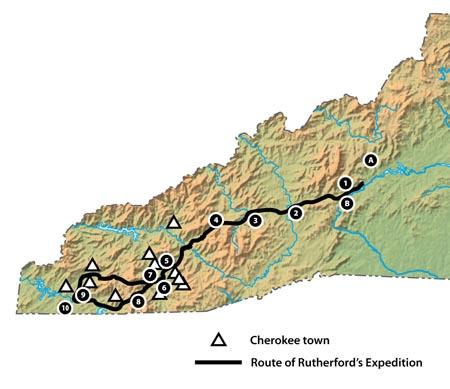

At Davidson's Fort at the head of the Catawba, Rutherford gathered his forces. On 1 Sept. 1776 he marched toward the mountains with about 1,700 troops, leaving about 400 men to protect forts in Tryon, Rowan, and Surry Counties. Rutherford crossed the Blue Ridge at Swannanoa Gap and followed portions of the Swannanoa River, Hominy Creek, the Pigeon River, and Richland Creek. They saw no American Indian people or members of the Cherokee tribe until reaching the latter stream on 6 September. Later that day, at Scott's Creek (a tributary of the Tuckasegee River), the first blood of the campaign was shed. An enslaved person belonging to John Scott, an American Indian trader, was mistaken for an American Indian person and was shot by the Reverend James Hall, chaplain of the expedition.

Over the next few days Rutherford's troops destroyed several Cherokee towns, including the Cherokee tribe's cornfields and food supplies. On September 16th, Rutherford and 1,200 men left Nikwasi to attack the Valley towns, leaving his remaining troops to wait for Williamson. When Williamson arrived at Nikwasi on September 18th, the South Carolinians marched after Rutherford. At Wayah Gap, they were ambushed by Cherokees and lost 12 men killed and 20 wounded in a two-hour battle before driving off the Cherokee ambushers.

On September 26th, Williamson and Rutherford linked forces on the Hiwassee. They decided against continuing the campaign to the Overhill towns, expecting that the Cherokee would block the mountain passes. On 27 September they began their return march.

The Rutherford and Williamson expeditions had burned 36 Cherokee towns. They recorded 12 Cherokees killed and 9 taken prisoner by Rutherford. Seven white men and 4 enslaved people were captured in the Cherokee towns, along with horses, livestock, and much plunder, including £2,500 worth of deerskins, powder, and lead. Although few Cherokee people were killed, the campaign cost them dearly in the loss of their towns and food for the winter. In mid-October 1776, Virginia forces brought the war to the still-unaffected Overhill settlements. After burning five towns, the Virginians negotiated a peace and returned home.

The defeat of the Cherokee in 1776 sharply reduced the threat of American Indian retaliation to the settlement of the frontiers of North Carolina and the other southern states. Many refugees from the towns destroyed by Rutherford and Williamson were scattered throughout the mountains; others found shelter with the Overhill Cherokee, and as many as 500 went as far as Florida, where they were aided by the British. Cherokee strength and morale were shattered, and the credibility of the British as American Indian allies was damaged. Had the Cherokee been able to mount a serious attack on the frontier country in 1780 and 1781, the outcome of the British Southern Campaign and the American Revolution itself might have been different.