Part i: Introduction; Part ii: American Indian people before European contact; Part iii: American Indian tribes from European contact to the era of removal; Part iv: The struggle for American Indian tribal sovereignty and cultural identity; Part v: North Carolina American Indian people today; Part vi: References

While North Carolina’s native tribes retained a hard-won degree of cultural and even political independence during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the lives of most Indians grew ever more impoverished and practically inconsequential in the eyes of the growing white community. The story of the Lumbee tribe, living in Robeson, Hoke, and Scotland Counties, is an example of this trend. Although the facts of their tribal history have been the subject of debate, the Lumbee likely are descendants of Saura and other Siouan speaking natives who survived the European onslaught by living in swampy lands unattractive to white settlers. They had adopted much of white settler culture—most notably, speaking English and adopting Christian beliefs—by the time white North Carolinians began to take note of the Lumbee as culturally different in the first decades of the nineteenth century. For a time, the Lumbee people maintained their rights of citizenship. When North Carolina enacted a new state constitution in 1835, however, which restricted the rights of ‘‘persons of color,’’ nearly all Lumbee civil rights were taken away. Through much of the remainder of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Lumbee people were victimized by prejudice and segregation, and they were left without the meager protections secured by other tribes through treaties with the federal government.

American Indians in North Carolina played a complex role in the secession crisis and Civil War. The Oconaluftee Cherokee, encouraged by secessionist and Indian agent William Holland Thomas, offered soldiers to the Confederate cause, and other North Carolinians of Indian descent undoubtedly fought for the Confederacy. But among the Lumbee people, a band led by Henry Berry Lowry did what it could to further the Union cause. Lowry organized attacks on Confederate leaders as well as wealthy whites. His exploits, which lasted until the early 1870s, made him a popular hero among the Lumbee as well as with some blacks and poor whites.

While Reconstruction and the push for new civil rights for people of color initially offered some hope of improved circumstances for American Indians in North Carolina, this promise quickly disappeared. The federal and state governments did, however, offer some limited educational and other benefits to the state’s native peoples. In 1885 the state officially recognized the Indian people living around Robeson County with the name ‘‘Croatan’’ (the name ‘‘Lumbee’’ did not officially designate the tribe until 1953), and separate schools were provided for their use, beginning with the Croatan Normal Indian School in Robeson County in 1887. This school, which granted its first college degree in 1940, became part of the University of North Carolina system in 1969 as Pembroke State University and later the University of North Carolina at Pembroke, offering crucial opportunities to Indian people.

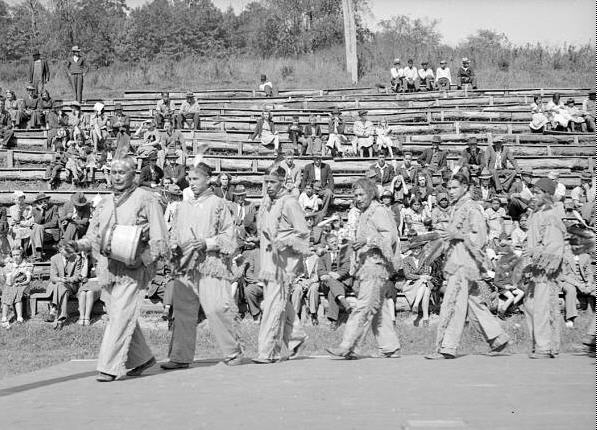

Among the Cherokee, Chief Nimrod Jarrett Smith negotiated with the North Carolina government on behalf of the Oconaluftee, and in 1889 they were recognized by the state as the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians with a status that allowed the tribe to function as a separate political body. Later, in the 1930s, the federal government extended a number of economic, educational, and other programs to Cherokee people. These programs improved the circumstances of many Cherokees while allowing the tribe to retain elements of its political and cultural autonomy. With the development of largescale tourism in western North Carolina coinciding with the opening of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in 1934, some Cherokee people capitalized on the opportunity to promote their cultural heritage as a part of the region’s appeal. While the Cherokee were drawn out of their regional isolation and afforded modest economic gains, some changes did not benefit the tribe. Tourists’ expectations of encountering ‘‘cigar store Indians’’ reinforced stereotypes among non-Indian visitors, and increased contact with the larger world presented Cherokee people with new struggles in their efforts to maintain traditional ways of life.

Despite some achievements in the first half of the twentieth century, the majority of American Indians in North Carolina continued to suffer from a lack of economic opportunities, poor access to education and health benefits, a sharply limited political voice, and persistent racism. Many American Indian people who had in the nineteenth century moved to marginal lands that were not valued by whites to avoid removal or other confrontation remained mired in relative obscurity. This was particularly true of the state’s smaller Indian tribes.

Nevertheless, many Indian people created businesses, churches, schools, newspapers, and other institutions in North Carolina, finding ways to promote their own sense of culture and identity while insisting upon a greater voice in state affairs. Indian leaders often concentrated their efforts on the development of separate schools. Members of the Waccamaw tribe, whose territory is centered in modern-day Bladen and Columbus Counties, first established a tribal school with their own funds in 1891 and maintained it through much of the next century. The East Carolina Indian School, founded in 1942 in Sampson County, was another important institution for the state’s Indian people. Occasional advances were also made politically. The predominantly Lumbee town of Pembroke elected its first Indian mayor in 1947. Sometimes Indian people found it necessary to confront opposition forcefully. In one notable instance of Indian resistance to white racism, a large group of armed Lumbee Indians confronted a Ku Klux Klan rally held on 18 Jan. 1958 near the town of Maxton. The Lumbees drove off Klan members and effectively put an end to Klan activity against Indian people in the area, drawing attention from state and national media who viewed the events in the context of the emerging civil rights movement.