"We ask nothing at the hands of the nation but equal Justice in common with other men."

-- Reverend Hurley Grimes, petitioning the Freedmen's Bureau on behalf of the Farmer's Association of James City, February 5, 1868

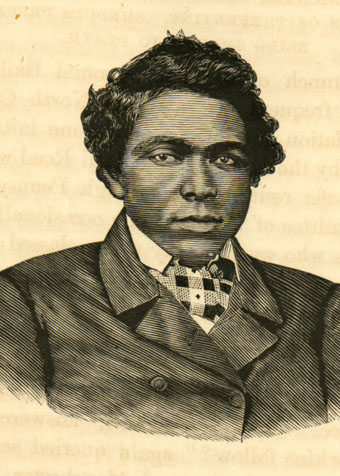

In May 1864, Abraham Galloway, John Good, and three other black men from North Carolina traveled to Washington, D.C., to meet President Abraham Lincoln and promote suffrage for black Americans. Galloway and his peers believed that political power would be the surest defense against discrimination. After this meeting and a subsequent visit to the National Convention of Colored Citizens of the United States in Syracuse, New York, in October, Galloway and others began forming state and local chapters of the Equal Rights League to press for political equality.

At the Civil War's conclusion, the black communities in eastern North Carolina were often better equipped to fight for political rights than were their counterparts in other parts of the South. Having tasted freedom during the war, freedmen and women had already begun grassroots political organization.

President Andrew Johnson directed the first phase of national political reconstruction. He pardoned most Confederates, allowed white southerners to control their state governments, and took few measures to protect freed people. In North Carolina, white antebellum leaders met to draft a new state constitution on September 21, 1865. They enacted "Black Codes," which limited black Americans' political rights, mobility, and employment, relegating them to second-class status. The next year, they refused to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, which extended citizenship to black Americans.

During the constitutional convention, 117 black delegates from 42 North Carolina counties met at a Freedmen's Convention in Raleigh. The men called for voting rights, full citizenship, public education, worker protection, and an end to discrimination.

Meanwhile in Washington, Congress -- disapproving of Johnson's leniency toward the South -- refused to allow North Carolina and other southern states back into the Union. During the congressional races of 1866, a "radical" element of the Republican Party gained power and ultimately took over responsibility for Reconstruction. This instituted a second phase in reunion, Congressional Reconstruction.

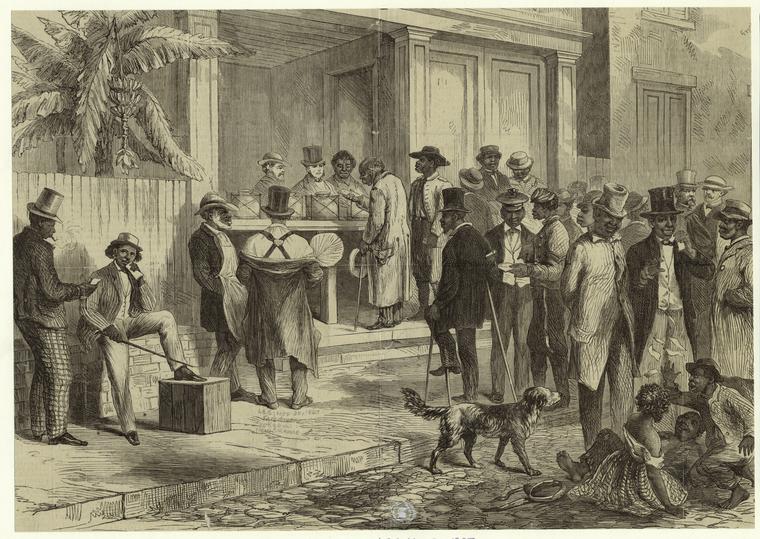

Congress divided the South into military districts and registered only voters who could take a loyalty oath to the United States and swear that they had not aided the Confederacy. These conditions prevented most white southerners from voting and presented a window of opportunity for black Americans.

Before Congress would re-admit North Carolina to the Union, a more liberal constitution was required. In 1868, a second state constitutional convention convened. Of the three delegates from Craven County who participated in the convention, one was black, Clinton D. Pierson. The new constitution and the state's adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment cleared the way for North Carolina to re-enter the United States that year. In 1870, states passed the Fifteenth Amendment, which ensured citizens the right to vote regardless of race.

At the local level, black Americans took advantage of their new political rights. They joined the Union League -- the political arm of the Freedmen's Bureau -- and the Abraham Lincoln League. These organizations facilitated voter registration and recruited black people into the Republican Party. The "Colored Men of New Bern" wrote about their new freedom in a newspaper editorial, stating, "We have got it, and we intend to keep it, and so not intend to jeopardize it."

Craven County's black majority helped elect several state representatives during the Reconstruction years. Of thirty-two black legislators who served in the General Assembly from 1868 to 1872, four came from Craven County. Five black justices of the peace were appointed locally during this period, and several other black Americans served as councilmen and aldermen. The political gains made by black people during the years following emancipation were significant, if short-lived.

Source Citation:

Exhibit Text, Claiming Citizenship: Political Activism, Days of Jubilee, Tryon Palace, New Bern, N.C.