In the 1830s and 1840s the United States was swept by what one historian has described as a ferment of humanitarian reform. Temperance, penal reform, women's rights, and the antislavery movement, among others, sought to focus public attention on social problems and agitated for improvement. Important among these reform movements was the promotion of a new way of thinking about and treating mental illness. Traditionally, people with mental illnesses could not be kept with their families became the responsibility of local government, and were often kept in common jails or poorhouses where they received no special care or medical treatment. Reformers sought to create places of refuge for people with mental illnesses where they could be cared for and treated. By the late 1840s, all but two of the original thirteen states had created hospitals for people with mental illnesses, or had made provision to care for them in existing state hospitals. Only North Carolina and Delaware had done nothing.

Interest in the treatment of mental illness had been expressed in North Carolina in 1825 and 1838 but with no results. Several governors suggested care of people with mental illnesses to the General Assembly as a legislative priority, but no bill was passed. Then in the autumn of 1848 the champion of the cause of treatment of people with mental illnesses made North Carolina the focus of her efforts. Dorothea Lynde Dix was a New Englander born in 1802. Shocked by what she saw of the treatment of women with mental illnesses in Boston in 1841 she became a determined campaigner for reform and was instrumental in improving care for people with mental illnesses in state after state.

In North Carolina Dix followed her established pattern of gathering information about local conditions which she then incorporated into a "memorial" for the General Assembly. Warned that the Assembly, almost equally divided between Democrats and Whigs, would shy from any legislation which involved spending substantial amounts of money, Dix nevertheless won the support of several important Democrats led by Representative John W. Ellis who presented her memorial to the Assembly and maneuvered it through a select committee to the floor of the House of Commons. There, however, in spite of appeals to state pride and humanitarian feeling, the bill failed. Dix had been staying in the Mansion House Hotel in Raleigh during the legislative debate. There she went to the aid of a fellow guest, Mrs. James Dobbins, and nursed her through her final illness. Mrs. Dobbins's husband was a leading Democrat in the House of Commons, and her dying request of him was to support Dix's bill. James Dobbins returned to the House and made an impassioned speech calling for the reconsideration of the bill. The legislation passed the reconsideration vote and on the 29th day of January, 1849, passed its third and final reading and became law.

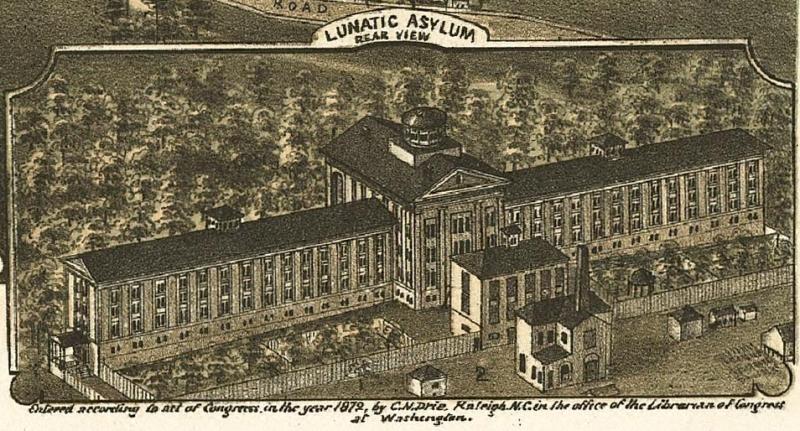

For the next seven years construction of the new hospital advanced slowly on a hill overlooking Raleigh, and it was not until 1856 that the facility was ready to admit its first patients. Dorothea Dix refused to allow the hospital to be named after herself, although she did permit the site on which it was built to be called Dix Hill in honor of her father. One hundred years after the first patient was admitted, the General Assembly voted to change the name of Dix Hill Asylum to Dorothea Dix Hospital.