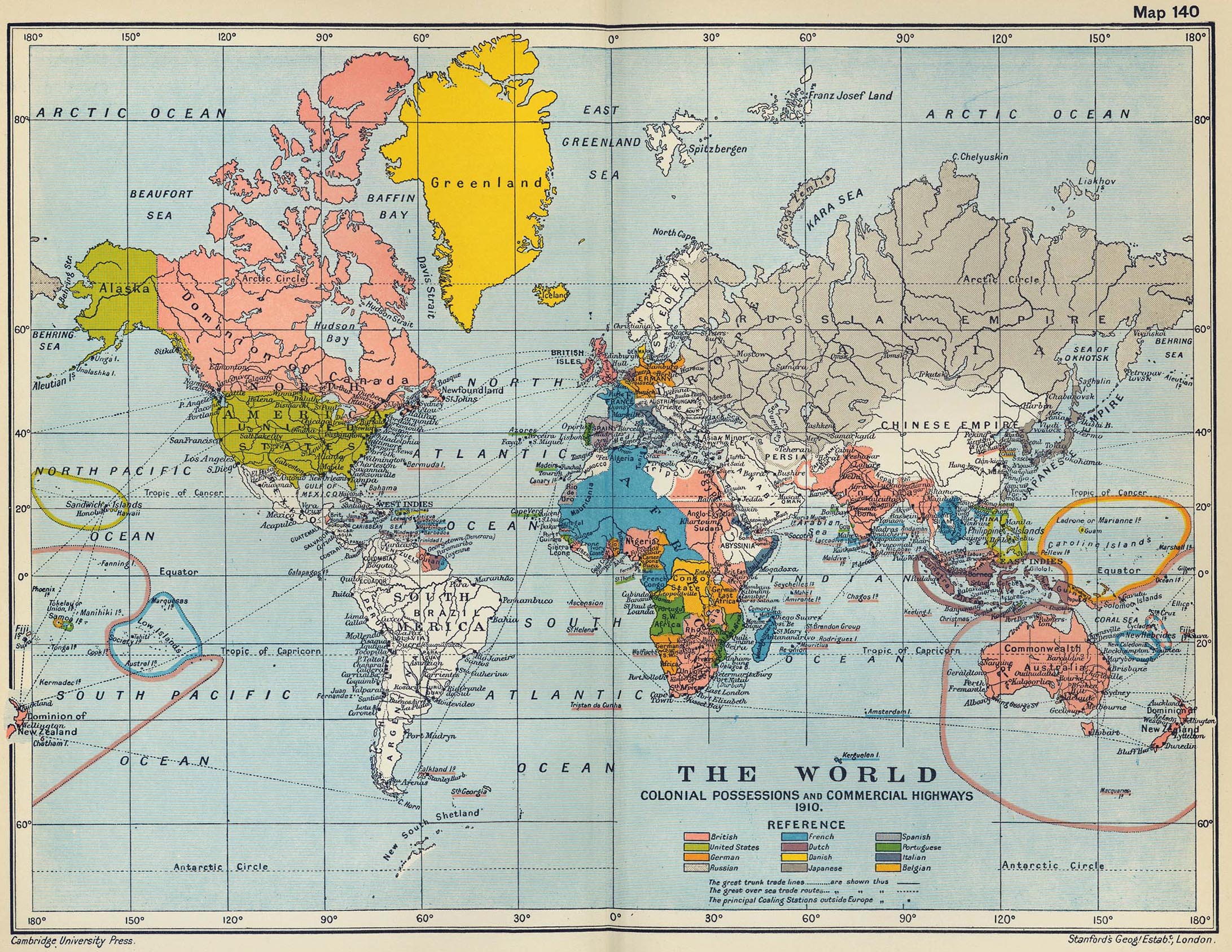

The last decades of the 19th century were a period of imperial expansion for the United States. The American story took a different course from that of its European rivals, however, because of the U.S. history of struggle against European empires and its unique democratic development.

The sources of American expansionism in the late 19th century were varied. Internationally, the period was one of imperialist frenzy, as European powers raced to carve up Africa and competed, along with Japan, for influence and trade in Asia. Many Americans, including influential figures such as Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Cabot Lodge, and Elihu Root, felt that to safeguard its own interests, the United States had to stake out spheres of economic influence as well. That view was seconded by a powerful naval lobby, which called for an expanded fleet and network of overseas ports as essential to the economic and political security of the nation. More generally, the doctrine of "manifest destiny," first used to justify America's continental expansion, was now revived to assert that the United States had a right and duty to extend its influence and civilization in the Western Hemisphere and the Caribbean, as well as across the Pacific.

At the same time, voices of anti-imperialism from diverse coalitions of Northern Democrats and reform-minded Republicans remained loud and constant. As a result, the acquisition of a U.S. empire was piecemeal and ambivalent. Colonial-minded administrations were often more concerned with trade and economic issues than political control.

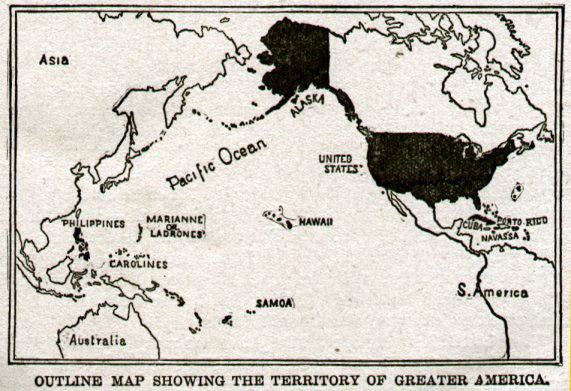

The United States' first venture beyond its continental borders was the purchase of Alaska - sparsely populated by Inuit and other native peoples - from Russia in 1867. Most Americans were either indifferent to or indignant at this action by Secretary of State William Seward, whose critics called Alaska "Seward's Folly" and "Seward's Icebox." But 30 years later, when gold was discovered on Alaska's Klondike River, thousands of Americans headed north, and many of them settled in Alaska permanently. When Alaska became the 49th state in 1959, it replaced Texas as geographically the largest state in the Union.

The Spanish-American War, fought in 1898, marked a turning point in U.S. history. It left the United States exercising control or influence over islands in the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific.

By the 1890s, Cuba and Puerto Rico were the only remnants of Spain's once vast empire in the New World, and the Philippine Islands comprised the core of Spanish power in the Pacific. The outbreak of war had three principal sources: popular hostility to autocratic Spanish rule in Cuba; U.S. sympathy with the Cuban fight for independence; and a new spirit of national assertiveness, stimulated in part by a nationalistic and sensationalist press.

By 1895 Cuba's growing restiveness had become a guerrilla war of independence. Most Americans were sympathetic with the Cubans, but President Cleveland was determined to preserve neutrality. Three years later, however, during the administration of William McKinley, the U.S. warship Maine, sent to Havana on a "courtesy visit" designed to remind the Spanish of American concern over the rough handling of the insurrection, blew up in the harbor. More than 250 men were killed. The Maine was probably destroyed by an accidental internal explosion, but most Americans believed the Spanish were responsible. Indignation, intensified by sensationalized press coverage, swept across the country. McKinley tried to preserve the peace, but within a few months, believing delay futile, he recommended armed intervention.

The war with Spain was swift and decisive. During the four months it lasted, not a single American reverse of any importance occurred. A week after the declaration of war, Commodore George Dewey, commander of the six-warship Asiatic Squadron then at Hong Kong, steamed to the Philippines. Catching the entire Spanish fleet at anchor in Manila Bay, he destroyed it without losing an American life.

Meanwhile, in Cuba, troops landed near Santiago, where, after winning a rapid series of engagements, they fired on the port. Four armored Spanish cruisers steamed out of Santiago Bay to engage the American navy and were reduced to ruined hulks.

From Boston to San Francisco, whistles blew and flags waved when word came that Santiago had fallen. Newspapers dispatched correspondents to Cuba and the Philippines, who trumpeted the renown of the nation's new heroes. Chief among them were Commodore Dewey and Colonel Theodore Roosevelt, who had resigned as assistant secretary of the navy to lead his volunteer regiment, the "Rough Riders," to service in Cuba. Spain soon sued for an end to the war. The peace treaty signed on December 10, 1898, transferred Cuba to the United States for temporary occupation preliminary to the island's independence. In addition, Spain ceded Puerto Rico and Guam in lieu of war indemnity, and the Philippines for a U.S. payment of $20 million.

Officially, U.S. policy encouraged the new territories to move toward democratic self-government, a political system with which none of them had any previous experience. In fact, the United States found itself in a colonial role. It maintained formal administrative control in Puerto Rico and Guam, gave Cuba only nominal independence, and harshly suppressed an armed independence movement in the Philippines. (The Philippines gained the right to elect both houses of its legislature in 1916. In 1936 a largely autonomous Philippine Commonwealth was established. In 1946, after World War II, the islands finally attained full independence.)

U.S. involvement in the Pacific area was not limited to the Philippines. The year of the Spanish-American War also saw the beginning of a new relationship with the Hawaiian Islands. Earlier contact with Hawaii had been mainly through missionaries and traders. After 1865, however, American investors began to develop the islands' resources - chiefly sugar cane and pineapples.

When the government of Queen Liliuokalani announced its intention to end foreign influence in 1893, American businessmen joined with influential Hawaiians to depose her. Backed by the American ambassador to Hawaii and U.S. troops stationed there, the new government then asked to be annexed to the United States. President Cleveland, just beginning his second term, rejected annexation, leaving Hawaii nominally independent until the Spanish-American War, when, with the backing of President McKinley, Congress ratified an annexation treaty. In 1959 Hawaii would become the 50th state.

To some extent, in Hawaii especially, economic interests had a role in American expansion, but to influential policy makers such as Roosevelt, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, and Secretary of State John Hay, and to influential strategists such as Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan, the main impetus was geostrategic. For these people, the major dividend of acquiring Hawaii was Pearl Harbor, which would become the major U.S. naval base in the central Pacific. The Philippines and Guam complemented other Pacific bases - Wake Island, Midway, and American Samoa. Puerto Rico was an important foothold in a Caribbean area that was becoming increasingly important as the United States contemplated a Central American canal.

U.S. colonial policy tended toward democratic self-government. As it had done with the Philippines, in 1917 the U.S. Congress granted Puerto Ricans the right to elect all of their legislators. The same law also made the island officially a U.S. territory and gave its people American citizenship. In 1950 Congress granted Puerto Rico complete freedom to decide its future. In 1952, the citizens voted to reject either statehood or total independence, and chose instead a commonwealth status that has endured despite the efforts of a vocal separatist movement. Large numbers of Puerto Ricans have settled on the mainland, to which they have free access and where they enjoy all the political and civil rights of any other citizen of the United States.

The canal and the Americas

The war with Spain revived U.S. interest in building a canal across the isthmus of Panama, uniting the two great oceans. The usefulness of such a canal for sea trade had long been recognized by the major commercial nations of the world; the French had begun digging one in the late 19th century but had been unable to overcome the engineering difficulties. Having become a power in both the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, the United States saw a canal as both economically beneficial and a way of providing speedier transfer of warships from one ocean to the other.

At the turn of the century, what is now Panama was the rebellious northern province of Colombia. When the Colombian legislature in 1903 refused to ratify a treaty giving the United States the right to build and manage a canal, a group of impatient Panamanians, with the support of U.S. Marines, rose in rebellion and declared Panamanian independence. The breakaway country was immediately recognized by President Theodore Roosevelt. Under the terms of a treaty signed that November, Panama granted the United States a perpetual lease to a 16-kilometer-wide strip of land (the Panama Canal Zone) between the Atlantic and the Pacific, in return for $10 million and a yearly fee of $250,000. Colombia later received $25 million as partial compensation. Seventy-five years later, Panama and the United States negotiated a new treaty. It provided for Panamanian sovereignty in the Canal Zone and transfer of the canal to Panama on December 31, 1999.

The completion of the Panama Canal in 1914, directed by Colonel George W. Goethals, was a major triumph of engineering. The simultaneous conquest of malaria and yellow fever made it possible and was one of the 20th century's great feats in preventive medicine.

Elsewhere in Latin America, the United States fell into a pattern of fitful intervention. Between 1900 and 1920, the United States carried out sustained interventions in six Western Hemispheric nations - most notably Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua. Washington offered a variety of justifications for these interventions: to establish political stability and democratic government, to provide a favorable environment for U.S. investment (often called dollar diplomacy), to secure the sea lanes leading to the Panama Canal, and even to prevent European countries from forcibly collecting debts. The United States had pressured the French into removing troops from Mexico in 1867. Half a century later, however, as part of an ill-starred campaign to influence the Mexican revolution and stop raids into American territory, President Woodrow Wilson sent 11,000 troops into the northern part of the country in a futile effort to capture the elusive rebel and outlaw Francisco "Pancho" Villa.

Exercising its role as the most powerful - and most liberal - of Western Hemisphere nations, the United States also worked to establish an institutional basis for cooperation among the nations of the Americas. In 1889 Secretary of State James G. Blaine proposed that the 21 independent nations of the Western Hemisphere join in an organization dedicated to the peaceful settlement of disputes and to closer economic bonds. The result was the Pan-American Union, founded in 1890 and known today as the Organization of American States (OAS).

The later administrations of Herbert Hoover (1929-33) and Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933-45) repudiated the right of U.S. intervention in Latin America. In particular, Roosevelt's Good Neighbor Policy of the 1930s, while not ending all tensions between the United States and Latin America, helped dissipate much of the ill-will engendered by earlier U.S. intervention and unilateral actions.

The United States and Asia

Newly established in the Philippines and firmly entrenched in Hawaii at the turn of the century, the United States had high hopes for a vigorous trade with China. However, Japan and various European nations had acquired established spheres of influence there in the form of naval bases, leased territories, monopolistic trade rights, and exclusive concessions for investing in railway construction and mining.

Idealism in American foreign policy existed alongside the desire to compete with Europe's imperial powers in the Far East. The U.S. government thus insisted as a matter of principle upon equality of commercial privileges for all nations. In September 1899, Secretary of State John Hay advocated an "Open Door" for all nations in China - that is, equality of trading opportunities (including equal tariffs, harbor duties, and railway rates) in the areas Europeans controlled. Despite its idealistic component, the Open Door, in essence, was a diplomatic maneuver that sought the advantages of colonialism while avoiding the stigma of its frank practice. It had limited success.

With the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, the Chinese struck out against foreigners. In June, insurgents seized Beijing and attacked the foreign legations there. Hay promptly announced to the European powers and Japan that the United States would oppose any disturbance of Chinese territorial or administrative rights and restated the Open Door policy. Once the rebellion was quelled, Hay protected China from crushing indemnities. Primarily for the sake of American good will, Great Britain, Germany, and lesser colonial powers formally affirmed the Open Door policy and Chinese independence. In practice, they consolidated their privileged positions in the country.

A few years later, President Theodore Roosevelt mediated the deadlocked Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, in many respects a struggle for power and influence in the northern Chinese province of Manchuria. Roosevelt hoped the settlement would provide open-door opportunities for American business, but the former enemies and other imperial powers succeeded in shutting the Americans out. Here as elsewhere, the United States was unwilling to deploy military force in the service of economic imperialism. The president could at least content himself with the award of the Nobel Peace Prize (1906). Despite gains for Japan, moreover, U.S. relations with the proud and newly assertive island nation would be intermittently difficult through the early decades of the 20th century.

Source Citation:

"An Outline of American History," United States Information Agency. https://archive.org/details/OutlineOfUSHistory/page/n181/mode/2up