Introduction

During World War II, the conflict between the United States and Japan increased existing anti-Asian discrimination and racism for Asian people living in the United States, specifically Japanese American people. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, fears of foreign threats and security risks at the hands of Japanese Americans soared. In response to these fears, and with no evidence of wrongdoing, tens of thousands of Japanese-Americans were forced to vacate their homes and abandon their property by the United States military and government. After being forced from their property, Japanese Americans were relocated to prison camps across seven states and held there for most of World War II, from 1942 until 1946 when the last camp closed.

Anti-Asian Sentiments and Legislation Before World War II

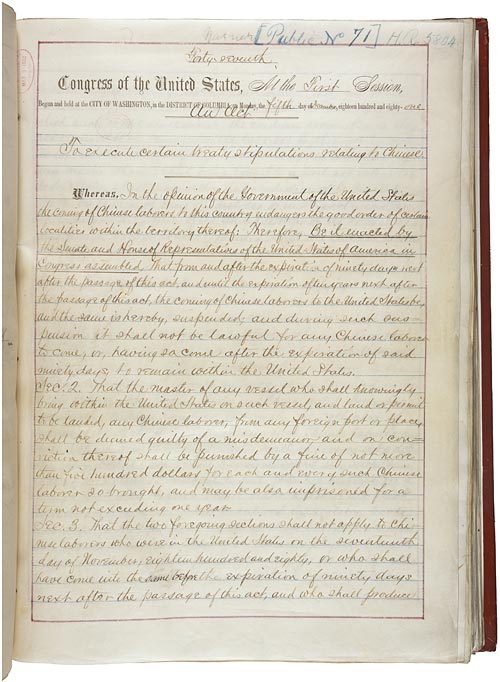

Anti-Asian sentiments and violence in the United States began long before the onset of World War II. Asian Americans were subjected to discrimination, including in state and federal legislation beginning in the mid and late nineteenth century. Initially, Chinese laborers were welcomed to the United States under the 1868 Burlingame-Seward Treaty. This treaty established favorable immigration and legal standards for Chinese people in the United States and American people in China. Wealthy business and industry leaders appreciated the influx of Chinese laborers that could be paid for less than their American counterparts. These laborers were important, particularly in the Gold Rush. However, as gold became less common and the Gold Rush calmed, anti-Asian sentiment began to increase. Communities and government leaders became more xenophobic (fearful of different groups of people) and began to enact legislation to support these mindsets and limit immigration. The Page Act of 1875 banned all Chinese women from immigrating to the United States and was the first ever federal law to restrict immigration. Less than a decade later, The Chinese Immigration Exclusion Bill passed in 1882 barred Chinese men from immigrating to the United States. The Scott Act of 1888 banned Chinese laborers from leaving and then reentering the United States. The Geary Act of 1892 made immigration even more difficult for Chinese people living in and coming to the United States. It required Chinese people to carry "green cards" to prove that they had immigrated legally, and any Chinese person found without one was subject to detention and deportation.

Japanese immigrants (called Issei) began arriving in the United States around the time of the passage of these laws primarily intended to limit the number of Chinese immigrants entering the United States. Japanese immigrants primarily settled in places like Hawai'i or along the West Coast of the United States. Specific fear surrounding first generation Japanese immigrants and their American-born children (called Nisei) followed the Russo-Japanese War. The Japanese victory over Russia as well as an increase in people immigrating to the United States from Japan led to an increasingly hostile environment for Japanese people in the United States well before World War II. In 1913 and again in 1920, California passed strict Alien Land Laws which prohibited ownership, leasing, and sharecropping of agricultural land to "aliens ineligible to citizenship," including Japanese immigrants. Alien Land Laws were also passed during this period in other western states, like Washington, in 1921.

Recently settled Japanese farmers had been more successful at raising crops than white farmers due to cultural farming practices. This further stimulated fear of them as a long-term threat among white farmers and investors and prompted anti-Japanese legislation. Additionally, the Immigration Act of 1924 prohibited all further Japanese immigration, further demonizing both Issei and Nisei Japanese American people. These factors, when coupled with the military defeat of Russia, created an atmosphere where the Japanese people became known as "the Yellow Peril," and they were ultimately perceived as a level of threat to their neighbors' security, despite there being no basis for these fears.