In January, 1929, Governor O. Max Gardner held a meeting of state agricultural leaders to discuss ways and means of improving farming conditions and rural life in North Carolina. At this conference it was decided among other things that a long-time agricultural program for the state should be inaugurated. The State College Agricultural Department, employing the assistance and suggestions of successful farmers, was asked to prepare this program.

A detailed, long-time program was studied by agricultural leaders and it was decided to launch a well-organized Live-At-Home program, this effort to be a major undertaking until the state became as nearly as possible 100 per cent self-supporting in the production of food and feed.

In December, 1929, the Live-At-Home program was launched, with Dean I. O. Schaub, of State College, as active chairman, and the campaign was carried to all North Carolina counties. In carrying out this program, Dean Schaub had the hearty coöperation of the press of the state, the Vocational Education Division, the State Department of Education, the State Department of Agriculture, county agricultural advisory boards, the State Health Department, civic groups, manufacturing and industrial groups, and other agencies.

In an address to State leaders, Governor Gardner said in part: "The idea in the phrase Live-At-Home as it is being applied to agriculture in North Carolina today, is not a new or original idea. The fact that it is not new, however, is unimportant. Few of our ideas or our beliefs or our programs are new. Our new ideas are usually old notions adapted to new problems.

"Agriculture-farming in this state is faced today with many exceedingly difficult problems. Out of the thinking and planning and speaking about these problems by the leaders of the state, the phrase Live-At-Home was coined.

"The Live-At-Home program has for its main purpose the encouraging of all of us engaged in farming to grow for ourselves and to supply ourselves with all the food and feed-stuffs and livestock products necessary for family and farm consumption the year round. It would also encourage us to grow enough surplus to supply the small towns and the cities which are our logical markets; and it would encourage the city folks of this state to give a preference to the North Carolina farmer in their purchase of the supplies which he grows."

Large-Scale Rehabilitation Trends in North Carolina

Along with such plans as the Live-At-Home program, has gone an increasing conviction that thorough planning must be done for thousands of North Carolina's displaced tenants, small farmers and others of that marginal group which makes its living from the land. Such a plan contemplating supervised, coöperative farm coloniesIn cooperative farming, a group of farmers share the cost of equipment, seed, fertilizer, and other necessities. These farmers then help one another plant, tend, and harvest their crops. The goal of cooperative farms was to lessen the economic burden of farming and to provide each farmer with needed labor without having to hire workers., with money and capital goods advanced, to be secured by liens on the land and property, the plan being self-liquidatingThe state would lend farmers money and be repaid, or take the farmers' land as repayment, so that in the long run, the state wouldn't be out any money., was first submitted to a Social Service Conference at the University of North Carolina in July, 1933. The plan in outline form was then prepared for publication by Dr. Roy M. Brown, Director, Division of Social Service, N. C. ERA, and Charles A. Sheffield, Assistant to the Director of Extension, State College, working with Mrs. Thomas O'Berry, State Administrator, N. C. ERA. The plan is submitted in its entirety on page 281.

The Rural Rehabilitation Program, April-December, 1934

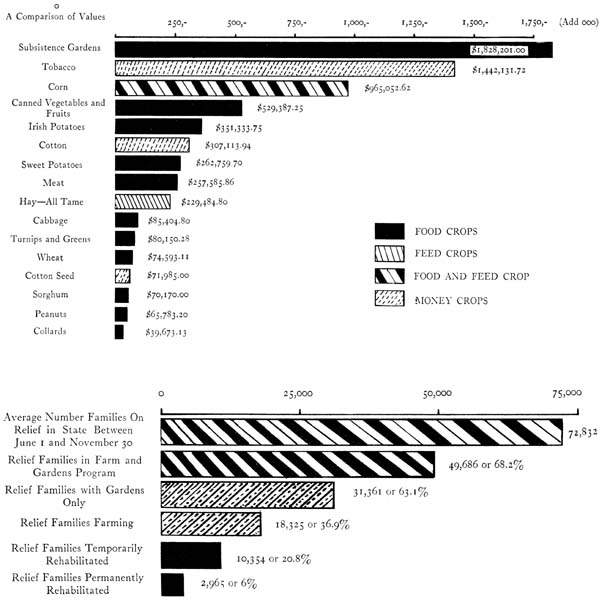

Beginning on April 1, 1934, the forementioned plan which had been forming for some time was put into effect. The relief program in rural areas was supplemented by a program of rural rehabilitation under direction of the Rural Rehabilitation Division. The aim was to make as many relief families as possible, with one or more able-bodied men, self-supporting by December 1. The result was that 10,354 families were temporarily removed from relief rolls, while 2,965 were permanently rehabilitated.

Relief families with farming experience were encouraged from the beginning to grow field crops. Signed agreements were made with landowners, securing the use of land in return for clearing or ditching the land, repairing buildings, or for a share of the crop.

A total of 6,469 agreements was signed covering 52,868 acres. Under these agreements, which were in the form of leases between landlord and tenant, 3,269 tenants gave a share of their crops, while 531 cleared or ditched land or gave other services for use of the land. Some landlords, financially able, with surplus land, coöperated splendidly by giving the use of land free to 1,737 tenants on relief, permitting them to retain all the crops.

During the effort to place families on farms as tenants through signed agreements between landlord and tenant, 11,856 additional families and 124 single persons were secured farm lands through share-crop agreements, thus increasing the number to 18,325 families and single persons growing field crops on 145,098 acres, or an average of 7.9 acres per farm.

To get the desired acreage, however, some families had to cultivate two or three separate tracts, on as many different farms, which sometimes consisted of very poor land. Very few of the families placed on farms had any work stock, or could secure the use of a neighbor's mule in exchange for work. Some had farm implements, but most had neither stock nor implements. The landlord in many cases provided work stock, but even then there was not enough to cultivate the acreage, only 7,077 mules, horses, or steers being obtainable for 18,000 farms and 31,000 gardens.

Through the State ERA office, 1,000 horses and mules, and some farm implements were purchased and distributed. Local relief administrations purchased 51 mules and 26 steers, and some farm implements to aid in the program. Some work stock plowed for as many as three or four families each week, such animals being known as ERA community stock.

During the planting period for field crops, family gardens were not neglected. Emphasis was laid on the necessity for each family to plant a garden or lose the right to any relief. The result was gratifying, in that 30,389 families and 972 single persons had gardens averaging an acre each. This was in addition to the 18,325 families who were farming, each of whom had a garden.

Through an educational campaign, all these relief cases, 49,686, were encouraged to own a cow, pigs and chickens. They were also stimulated to grow in their gardens and on their farms all food and feed crops possible, expert direction being given to the preserving of surplus products for winter use.

Seeds and plants were furnished by ERA to all relief families, and in some instances where it was impossible for the landlord or client to furnish fertilizer, the ERA furnished it. Some local relief administrations, in order to give work to many families with farming experience, not otherwise provided with work, cultivated 3,718 acres in community gardens to raise food and feed for relief purposes.

Where advances were made to the client, such as fertilizer, feed for his livestock until some could be raised, food, clothing, medicine, etc., repayment was to be made either in kind or by work done on ERA projects. Every person participating in this program understood that he or she must do everything possible to raise necessities, the ERA promising to assist and coöperate where necessary. All advances of cash and goods were to be rapaid. It was made clear that this program was not in the nature of a doleA dole is a charitable gift or handout. Since the plan involved a loan and farmers would work cooperatively, it was not simply a handout., but a coöperative enterprise between the individual and his government to help overcome the problems attendant upon the depression.

To obtain satisfactory results in any program, particularly an effort of this nature, a certain amount of competent supervision is necessary. Hence, during the planting and growing season a farm foreman, or farm supervisor, visited each garden and farm from time to time to see that planting and cultivating were being properly attended to, and to give counsel and advice. Special assistance and encouragement were given those whose crops were affected by drought, or excessive wet spells, during the summer when many crops were practically destroyed or cut very short in the yield.

The harvest of field crops was considered to be very good despite bad weather, poor land, and the shortage of work stock, farm implements, etc. The results obtained in this particular program speak well of the pride, determination and industry of those who, starting practically from nothing, evinced a desire to help themselves if means were provided.

The value of crops raised, estimated from available data, was more than $5,500,000.00. The meat produced was worth over $225,000.00. Housewives canned vegetables and fruit valued in excess of $500,000.00. Farms under the control of local relief administrations yielded more than $176,000.00 worth of food and feed crops for relief purposes.

The results of a county canning program are given here in the report of Iredell County. The figures included here show what is possible in a well-organized effort to can subsistence foods. An interesting thing to note is that in cases where canning instruction was given in the home, the canning instruction was adapted to the available facilities, and not to ideal canning facilities. Another profitable by-product of canning effort is the fact that a real desire to conserve fruits and vegetables has been stimulated.

Following are given the figures, in quarts, of foodstuffs canned in the 1934 program in Iredell County:

|

Quarts |

|

|---|---|

|

Beans |

29,444 |

|

Beets |

1,441 |

|

Apples |

11,436 |

|

Berries |

1,086 |

|

Cucumbers |

1,271 |

|

Peaches |

7,424 |

|

Plums |

23 |

|

Corn |

23,504 |

|

Grapes |

320 |

|

Okra |

1,503 |

|

Squash |

6 |

|

Tomatoes |

6,735 |

|

Kraut |

276 |

|

Carrots |

31 |

|

Soup Mixture |

4,578 |

|

Apricots |

3 |

|

Pears |

6,041 |

|

Damsons |

196 |

|

Pumpkin |

1,248 |

|

Peas |

4,810 |

|

Relish |

71 |

|

Potato |

3,770 |

|

Pickles |

1,794 |

|

Greens |

374 |

|

Persimmons |

39 |

|

Rhubarb |

32 |

|

Butterbeans |

2 |

|

Pepper |

4 |

|

Total Quarts Canned from Individual Gardens |

107,462 |

|

Quarts |

|

|---|---|

|

Beets |

429 |

|

Beans |

3,115 |

|

Cucumbers |

146 |

|

Corn |

2,364 |

|

Peaches |

103 |

|

Apples |

108 |

|

Soup Mixture |

1,489 |

|

Tomatoes |

855 |

|

Okra |

131 |

|

Figs |

3 |

|

Pickles |

12 |

|

Pears |

64 |

|

Total Quarts Canned from County or Community Gardens |

8,819 |

|

Quarts |

|

|---|---|

|

Beans |

1,628 |

|

Total Quarts Bought or Donated |

1,628 |

Canning centers, 16.

Canning demonstrated, etc., in relief homes, 83.

NOTE. In canning the above products, 70 per cent of the containers used was glass, thus allowing those containers to be used again after being sterilized.

North Carolina

A comparison of the values of 13 principal field crops, canned vegetables and fruits, subsistence gardens, and meat, produced by Relief Families in the Farm and Garden Program in 1934.

- Total estimated value of gardens, field crops, meat, etc.

$6,750,775.25 - Total estimated value of field crops grown by Administrative units

$176,733.74