On October 3, 1918, Governor Thomas Bickett issued the first order in North Carolina's battle with an enemy which would prove more deadly to the state than the soldiers of the Central Powers against whom troops from North Carolina were fighting thousands of miles away in Europe. A hitherto unknown strain of influenza had appeared in Wilmington and was spreading west over the state, following the rail lines. North Carolinians were familiar with older forms of influenza, often called the "grippe," which were debilitating but only occasionally deadly. The new type of flu struck fast, causing two or three days of high fever which, in a distressingly large number of cases, led to death. The lungs of victims filled with fluid and their skin turned a dark blue, as their respiratory system failed and their tissue was starved for oxygen. The old influenza was most dangerous for the weak or elderly; the new flu preyed on the young and healthy.

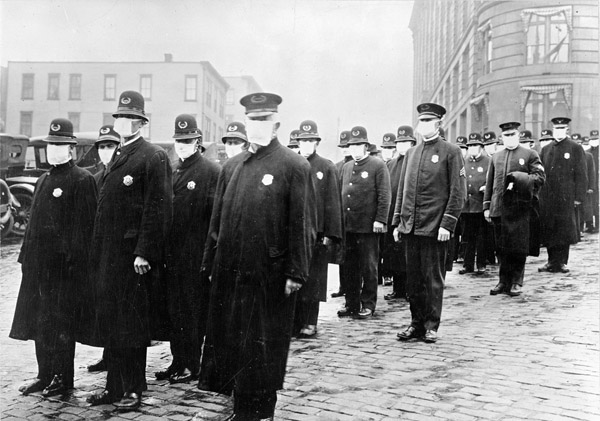

The influenza epidemic overwhelmed North Carolina's medical community and rudimentary public health system. The medicines and folk remedies on which people customarily relied were useless. The state's primary public health response—forbidding public gatherings and quarantining victims—began late and was almost impossible to enforce. When local public health services failed or where they were nonexistent, people working through war-preparedness groups and the Red Cross, organized volunteers to visit the sick and fetch medicine or food. Emergency kitchens were set up to cook for those too sick to help themselves.

What was happening in North Carolina was a part of the worst influenza pandemic in modern times. Present day research has identified the cause of the disease as an influenza A virus strain. The virus produced a violent reaction in the human immune system, which ironically led to the disease being deadliest among those whose systems were strongest, the young and fit. The virus swept in three waves through the populations of Europe and North America, already dislocated by World War I, and eventually spread to all parts of the earth. Overall, as many as 20 million people may have died.

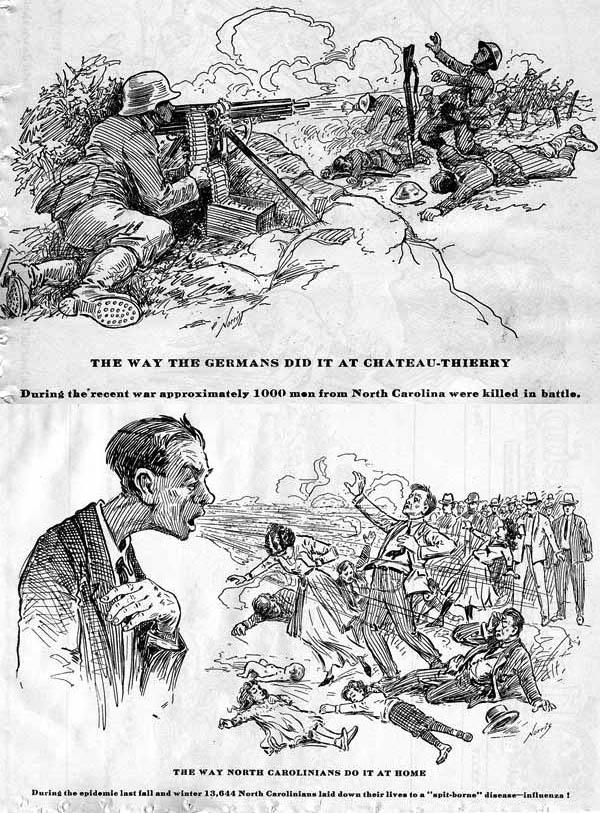

More than 13,000 of those dead came from North Carolina. Influenza killed people in all walks of life and was particularly deadly on those who cared for the sick, both professional and volunteer. It killed with something like the speed of modern warfare: in many cases less than 48 hours passed between the first sneeze and the last breath; the president of the University of North Carolina died near the beginning of the epidemic; his successor died a month later. Soldiers in crowded training camps were especially vulnerable. At the railroad station that served Camp Greene near Charlotte, coffins were stacked from floor to ceiling, taking home the bodies of young soldiers who never saw the war.

In some ways North Carolina benefited from the influenza epidemic. The 1920s witnessed an unprecedented boom in hospital construction in the state, fueled, at least in part, by the inadequacy of the old health care system, so graphically demonstrated in the epidemic. For much the same reason, the public health system began to take hold in North Carolina during the years following World War I. In the end, however, the disease, while deadly, was over quickly, and memory of the Blue Death faded. Old stories still circulate: a lonely house in the country where an entire family, parents and children, were found dead in their beds or the four country doctors serving an area at the beginning of the sickness, only two of whom were alive at the end or the woman who, on seeing a new-dug grave, said it reminded her of 1919, when the graveyards looked like they had been turned with a plow.