The below speech from J. Marvin Turner explains his experience working with the B-17 bombers that were commonplace by the U.S. military in World War II.

Transcript

This is the official speech I made fifty-two times during the sixth War Bonds Drive between November third and December twenty-second, 1944. It was heard by 5978 people.

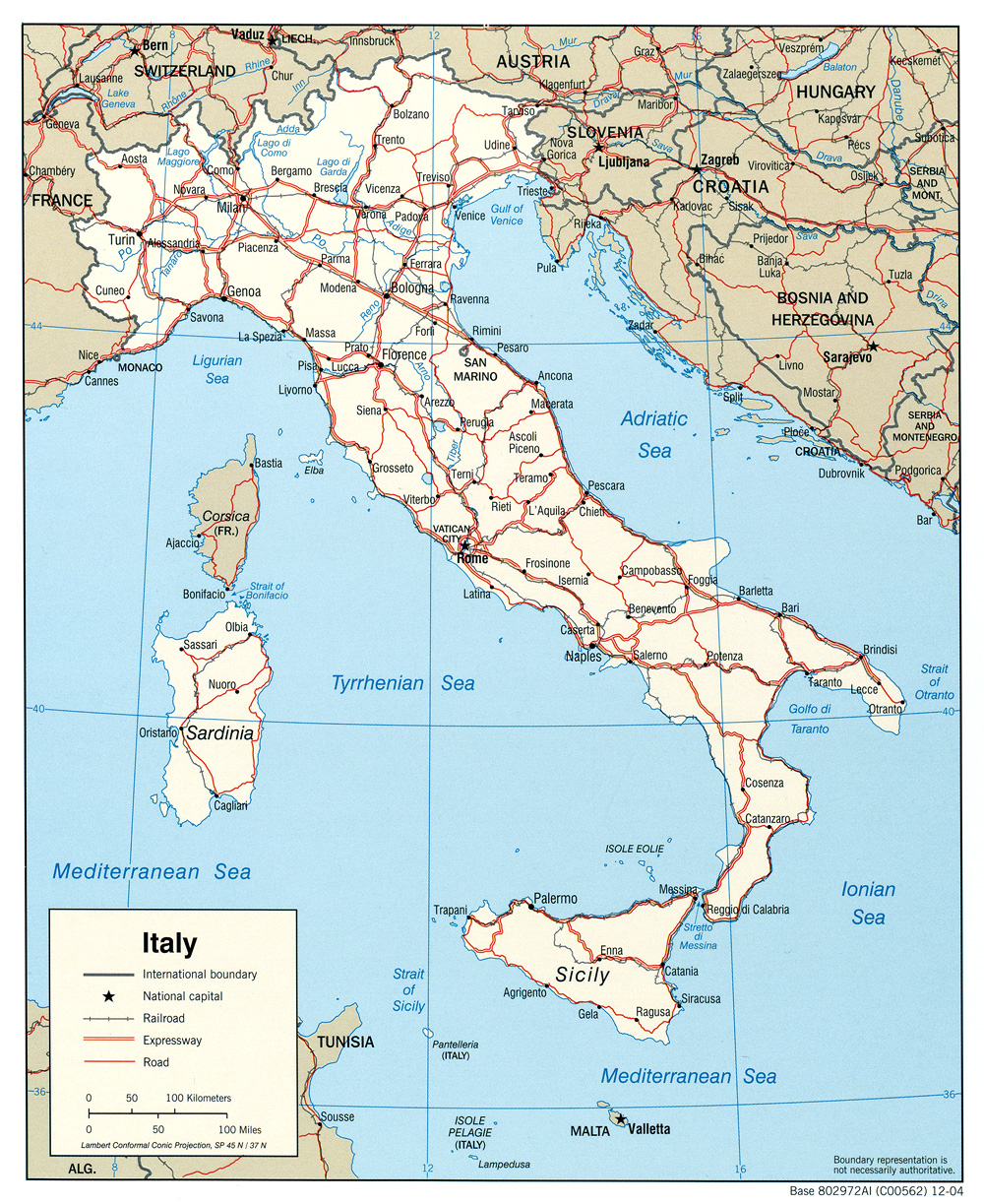

On January 23, 1944, our crew of ten on a B-17 landed on a base in Italy. We had been training and working together for about five months previous to this time. And we were all ready and eager for combat. That is what they gave us, and this is a story of what happened to that crew. At first we didn't fly together as a crew. They split us up and we flew individually with experienced crews.

On February twenty-fifth, just one month after we landed there, our radio operator was sent out with another crew on a mission to Riegelsberg, Germany. Fifty B-17s without escortWhenever possible, bombers were "escorted" by fighter planes. When the enemy spotted incoming bombers, they would, of course, respond by sending fighter planes to shoot them down. Bombers were big and not as easy to maneuver as fighter planes, and so the best protection for a bomber was to be accompanied by fighters. But fighters were not always available, and then bombers had to fly without escort. went on that mission and before it was completed, twenty were shot down. The figure twenty doesn't sound like much. But you have to stop and remember that there are ten men on each plane. That means 200 men went down. Not all of them were killed, but a good many of them were.

The plane that my radio operator was on was hit by an enemy fighter, went out of control, crashed into another plane, and they both went down together. Of the twenty fellows on those two planes, only three or four got out. My radio operator was one of the lucky ones. So he's now a prisoner at Stuttgart, Germany.

A B-17, or any heavy bomber, has but thirteen fifty-caliber guns on it. But they aren't much use when attacked by an overwhelming force of enemy fighters. Without fighter protection of our own, we don't stand much of a chance against the large number of enemies.

About a week later, on March second, I was flying with another crew over the Anzio beachheadA beachhead is the line created when a military unit first lands on a beach and defends it while waiting for reinforcements to arrive.. It seems the JerriesAmericans and British often informally referred to Germans as "Jerries" during World War II. The term probably comes from "Gerries," short for "German." The term would now be considered offensive. had a large concentration of troops, behind the lines, and were about to make a push to break up our beachhead. Intelligence found out about it and gave the job to the Air Force.

Our planes were loaded with anti-personnel bombs and we dropped them right over concentration. We must have done a good job because before that push was over — or that push, rather, was never made. However, the reason I remember that day is because the Jerries were so accurate with the anti-aircraft bombs, used against a lot of other planes that had been over there a number of times before, so that they had had a good bit of practice and really knew how to shoot.

As we were going straight down on a bomb run, I could see the shells bursting directly in front of us and knew that we were going to get hit. The first burst hit our number four engine. That's the outpouring and in the right wing. The oil began to pour out and it began to run wild — with the power going about three times as fast as it should. Thus causing a terrific vibration in the plane. Ordinarily we could shut it off and [fly it as a prop?] but the mechanism was shot away and there was nothing that we could do but let it run wild.

A second later, another burst hit the number three engine. That's the one on the, the other one on the right wing. And the same thing happened to it. The vibration the two flaps set up was so terrific that a piece of armor plate lying [in a piece?] on the radio room floor, weighed about thirty-five or forty pounds, [got up?] and came four to six inches off the floor. Another burst of it hit the Plexiglas hose and cut it completely off the bottom of the [?] with the navigator riding in the nose who never even got a scratch. However, there was colonel riding there also, just to see what combat was like. A piece of that shell burst right through his left foot, taking three toes with it, so he found out what combat was like in a hurry.

Another burst went through the radio room and made it look like a sieve. The radio operator was in there, but where, I can't imagine, because he didn't get a scratch. It's probably a good thing too because that was his fiftieth and last mission. A few days previous, on his forty-ninth mission, he had gotten five good-sized holes in his [?] so that he really wasn't able to fly now but he was so anxious to fly his fiftieth mission so that he could go home that he had begged the docs to release him so that he might complete his missions.

Another burst hit the ball turret. A piece of the burst went up through the turret, between the operator's legs and hit the sight, which was just an inch or two in front of his face. The sight was smashed all to pieces and the fuel and the parts were flying around inside the ball. However, the operator did not get a scratch. That's rather a good thing also, because he too was flying his fiftieth mission.

He decided that was no place for him so he came out of there in a hurry. I got down out of the upper turret about the same time because it was easy to see that that plane wasn't going to hold together long enough for us to get back to our base. I asked the pilot if there was anything I could do. He said, yes, hand him his parachute. So I gave he and the co-pilot their chutes, then picked up mine and walked back to the bomb base to the radio room where the operator was sending out SOS messages and then on into the waist where the rest of the boys were standing around with their parachutes on waiting for the order to bail out.

I put my chute on and then somebody said, "Kick out the emergency door." As engineer, that was my job. So I went over, pulled on the release, kicked on the door, but nothing happened. I pulled and kicked again. But still nothing happened. I did this three or four times and the door just stayed there. Finally, we located a screwdriver and pried on the emergency release until the door came off. This must have taken about five minutes. And if anything had happened in the meantime, we would have been dead ducks, because that was our only exit.

All nine of us were lined up there in the waist waiting for the order to bail out. I looked down and saw that we were flying over water. I wondered why that was since, if we were going to bail out, the best place to have done it, naturally, would have been over land. The pilot told us later that the reason we didn't bail out over land was because we had shot the anti-personnel bombs on the troops and had probably killed a good many of them. Naturally those that were left wouldn't have been very friendly, so they would no doubt have taken potshots at us as we came down. So he decided to go out to sea and take our chances on landing on the ocean.

Of course we didn't know this as we were standing back there, so we were still waiting to bail out. As I stood there looking at the water, I happened to notice that I had my wristwatch on and I thought, "doggone, I'm going to ruin this thing when I get in the water." That's a funny thing to think about at a time like that but that seemed to be my only concern right then.

Somebody suggested that we have a cigarette, so one of the waist gunners pulled out a brand new pack, opened them up, passed them around, and everybody stood there, smoking. We were all very calm and collected and didn't seem to be worried about a thing. I actually think we wanted to bail out and find out what it was like.

In a few minutes [hard to hear], it came over the interphone that we were going to ditch — that is, crash land on the ocean. We threw all the armor plate, ammunition, guns, everything that was loose in the waist of the plane out the door. Then we took off our parachutes, heavy flying boots, went back in the radio room, and sat down on the floor. We doubled up our knees in front of us, rested our back against the fellow's knees behind us, and cupped our hands behind the fellow's head in front of us. That was to keep his neck from snapping when we hit the water.

We were doing ninety miles an hour when we hit the water and we stopped instantly. We went from ninety miles an hour to zero in nothing flat. That shook us up quite a bit. The bulkhead come crashing up through the floor, back into the radio room, and a big hole opened in the side and the bottom of the ship. We were knocked out by the impact. But at the same time, the room half-filled with ice-cold water and revived us, so that we were knocked out and brought to all at the same time. The radio operator jumped up, pulled the release on the two life rafts.

I was the first one that got up, got to the raft on the left-hand side of the plane. I was supposed to cut the cord holding the raft to the ship. But the shock of landing had knocked the knife from my hand so that I had no way to do this. The pilot, who was also flying his fiftieth mission, got to the raft at about the same time I did. He said, "How we going to cut this thing loose?" I said, "I don't know but the rope is supposed to break when the plane goes down." He said, "Well, here's hoping."

We didn't have any more time to talk then because we had been standing on the wing, and just then the plane left us. It was less than thirty seconds from the time we hit the water until the plane was completely gone. The ropes did break all right. And the two rafts floated. However, there were three fellas still inside the radio room when the plane went down. Somehow, they got out. I don't know how and they don't either. They said later, the fellas, that someone reached in and pulled them out. We know that didn't happen. Because we were all too busy trying to save ourselves.

They popped to the surface a couple of yards away and managed to get to the raft okay. We started to climb in but with all of our heavy wet clothing on and a five-foot wave passing us around, it was quite a job trying to climb over the high sides of the raft.

As we were climbing in, we heard someone call. We turned around to see the eleventh man floating in the water about ten feet away from us. He must have been scared so badly he couldn't move because he made no attempt to swim or help himself in any way. He just stood there in the water with his life preserver holding him up and calling to us to come help him. We called to him and said that we would but there wasn't much we could do right then.

We continued climbing into the raft and by the time we were able to start paddling, the wind had blown us about seventy-five yards away from him. We continued to call to him and give him encouragement while we paddled but all that the paddling was doing was turning us in circles. Those rafts don't have any bow or stern so there was not way we could control the direction. Our young co-pilot, all about nineteen years old, said, "I can't sit here and watch him go down like that. I'm going after him." We argued with him, did everything we could to try and stop him. It was hard to lose one but it was much worse to lose two. And we knew that no one stood a chance in the water that day.

However, nothing we could say or do would stop him. He took off all his heavy equipment, everything but his light uniform, took two life preservers and threw them over. The fellow he was going after was at least a hundred yards away from us by then and we could just barely see his head bobbing up and down once in a while and very faintly hear his calls. The co-pilot got about fifty yards away and stopped to rest on a box that was floating there in the water. He called to us to come after him. We were paddling all the time but making no headway at all. We called to him and told him to come back to us. But he said, no, he was going on. With that, he let go of the box and started to swim again. He called to us several times after that and we continued to call to him until at the end of about twenty minutes we didn't get any answer. We never did see either of those two fellas again. We knew there was nothing more that we could do to help them so we set about trying to save ourselves.

We were completely out of sight of the mainland but we could see an island about fifteen miles away. Our paddling served only as a means to keep us warm, so we took off our scarves and tried to make a sail. However, they were too small and even though the wind was quite strong, they weren't any help.

In a few minutes we saw an airplane coming. We thought, well, good, we're going to be picked up right away. None of us had ever seen a British air, uh, rescue plane before, so we didn't know exactly what to look for and we started to signal the plane.To help soldiers and sailors learn to identify Allied and enemy airplanes from the ground, the military issued playing cards with silhouettes of planes on the fronts. You can see an example from Historical Ephemera. However, as it came closer, we began to feel sure that it wasn't friendly. And when it got up close to us, we found out that it was a German KU-88. It was just skimming the water and flying a little to one side of us, it went by so close that we could see the expression on the pilot's face. We tried to make ourselves as small as possible but there wasn't much of any place we could go out there.

I don't know if he didn't see us. I can't figure out how he could miss. But if he did see us, I don't know why he didn't come back and try to shoot us or pick us up. However, he just flew off and didn't come back. That gave us kind of a scare so that we were leery about trying to signal any more planes.

However, in a little while, we did see some planes that we knew were definitely British and that were looking for us. We also saw a rescue launch. They were all looking in the spot where our plane had gone down, while the wind had blown us about three miles away. They couldn't see us — we were just another speck on the ocean for them and we couldn't find our flares so that we could signal them. So we just had to sit there and watch them look for us, without being able to do anything. It was just like a game of hide and seek.

After four hours of floating around like that, one of the fellas was pushing around in the bottom of the raft and found a flare kit. At about the same time, one of the rescue planes flew fairly close overhead, so we fired three flares. We thought he didn't see us because he turned and went away while we were beginning to feel pretty low. We didn't know when another plane would be around.

However when he got down to the place where the launch was, he turned and started back in our direction. We knew then that he had seen us and had just gone down there to signal the launch, so we started to feel pretty good. He came back and continued to circle us and dropped smoke bombs on the water to indicate our position to the rescue launch. In a few minutes the launch came alongside and took us on board. That was only a little forty-five or forty foot boat. But it couldn't have looked better if it'd been the Queen MaryThe Queen Mary was an ocean liner that sailed the North Atlantic Ocean from 1936 to 1967. It was known for its luxury. itself.

They took us below deck, took off our wet clothing, rubbed us down good, and put warm, dry clothes on us. We just sat there on the table and they did everything for us just like we were babies. Sure made us feel pretty good.

The colonel was flat lying on the floor, biting his lip, and not saying anything. It had been about five hours since he lost his toes and we hadn't been able to give him any first aid, so he was in considerable pain. The launch had no facilities for treating him so they radioed a British destroyer that was in the area, that had a doctor on board, so they [sailed] up alongside and took the colonel off. I have heard since that he got all right and went back to his outfit and flew combat again. He certainly was a swell egg.

The launch took us on into the island we had seen and we stayed in the British officers' quarters for the next two days. The reason for this delay was because a very bad storm came up right after we got on the island and the water was so rough that the launch couldn't take us back to the mainland. It was a good thing they picked us up when they did or I am sure we would never have lasted the night out in that raft.

We finally got back to the mainland and our base and then they gave us some time off to rest up. I took a three-day pass and went down to [?] for my rest. I came back to the squadron on Friday night, March the 10th, I looked on the bulletin board and saw that my crew, the one I had come overseas with, was scheduled to fly the next day, as a complete crew for the first time. That is, everybody was going to fly their own position. Except the bombardier who was flying on the lead ship and another fella who was taking my place.

I went into operations, asked if I couldn't fly. Said that I was well rested, ready to start again and also since this was my crew's first time I wanted to be with them. Ed Morrow, the fella in charge of making up the roster said, "Aw, don't be eager. Take another day off. It'll do you good. And besides, you'll have plenty more chances to fly with your crew." I argued with him for a while longer but nothing I could say would make him change the roster, so I went back to my tent and went to bed.

The next morning, my crew got up, my best buddy, a fellow that I'd been with for about a year and a half and had luckily been put on the same crew with me, came over and woke me up and said, "In case anything happens today and I don't come back, you know where all my things are and what to do with them." Of course we had all made arrangements like this with one another in case some of us didn't come back, that those that were left would take care of a few of our personal articles as soon as they got home all right. However, we didn't talk much about that. So I said, "Aw go on, get outta here. I'll see ya this afternoon."

So he and the rest of the crew went out and flew on the mission. Went up to a target in northern Italy. Just a few B-17s without fighter escorts. There were no fighters to send with them. They went over the target and all but the lead plane dropped the bombs. They met no flak or fighters so they decided to make a big circle and go over the target a second time and let the lead plane dump its load.

While they were doing this, the Jerries had enough time to fit up a number of fighter planes. My crew was flying the last ship in the formation, a position known as Tail-end Charlie and always the first one to be attacked by fighters. The Jerries didn't waste any time this time and so hit the boys' ship with two rockets. It didn't go down right away. In fact, they even managed to stay in formation until they were ten or fifteen miles out over the Adriatic Sea, when their engines caught on fire. When that happens, you don't ask any questions, you just bail out in a hurry.

A few of the boys got out and then the plane blew up, completely disintegrated. And there was nothing left but a big puff of black smoke. When that happened, what happened to the rest of the boys, we don't know since we have never heard another word since that day. They were probably drowned or died of exposure in the water but there is a slight possibility that they might have been picked up by Italian fishing boats that might have been in the area. That's only a slim hope but we are holding on to itSoldiers and sailors lost in battle were considered missing in action (MIA) unless their bodies were found and positively identified. until the area is cleared and the underground is opened and all the boys are returned.

That left just two of us on the original crew still flying, the bombardier and myself. The bombardier got up to his twenty-fourth mission but on May 10th he was flying over a target in Austria. He stopped a good-sized piece of flak with his left arm and side. When I heard from him in October, he was still in the hospital over there and in such bad shape that he couldn't even be flown back to the States. He'd had thirteen operations and twenty-three blood transfusions. He really got banged up.

That left me all by myself. I did a lot of thinking. When you've lost all nine of your buddies you can't help but wonder sometimes what's going to happen next. I was put in a tent with five other fellows who had lost all their crew but themselves. So the six of us were the remains of six crews. We kept each other pretty good company.

I had pretty good luck from there on. And on July fourteenth, I flew my fiftieth and last mission over Budapest. When I came back, I got out and kissed the ground. I was pretty happy. I also said a good long prayer of thanks because you can't get through those things on just luck. It takes a lot more than that.

Well, that's the story of one crew. It's not an unusual or outstanding story. The same thing has happened to a good many crews before and will happen to a good many crews before this thing is over. It's not a pleasant thought but it's something that we all have to face. The only thing we can do back here to bring them back quickly and all in one piece is work like the dickens to support these War Bonds Drives a hundred percent. I know that's what you want and I'm also sure that you won't let us down.

Thank you.