With malice toward none

For the North, the war produced a still greater hero in Abraham Lincoln - a man eager, above all else, to weld the Union together again, not by force and repression but by warmth and generosity. In 1864 he had been elected for a second term as president, defeating his Democratic opponent, George McClellan, the general he had dismissed after Antietam. Lincoln's second inaugural address closed with these words:

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan - to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

Three weeks later, two days after Lee's surrender, Lincoln delivered his last public address, in which he unfolded a generous reconstruction policy. On April 14, 1865, the president held what was to be his last Cabinet meeting. That evening - with his wife and a young couple who were his guests - he attended a performance at Ford's Theater. There, as he sat in the presidential box, he was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth, a Virginia actor embittered by the South's defeat. Booth was killed in a shootout some days later in a barn in the Virginia countryside. His accomplices were captured and later executed.

Lincoln died in a downstairs bedroom of a house across the street from Ford's Theater on the morning of April 15. Poet James Russell Lowell wrote:

Never before that startled April morning did such multitudes of men shed tears for the death of one they had never seen, as if with him a friendly presence had been taken from their lives, leaving them colder and darker. Never was funeral panegyric so eloquent as the silent look of sympathy which strangers exchanged when they met that day. Their common manhood had lost a kinsman.

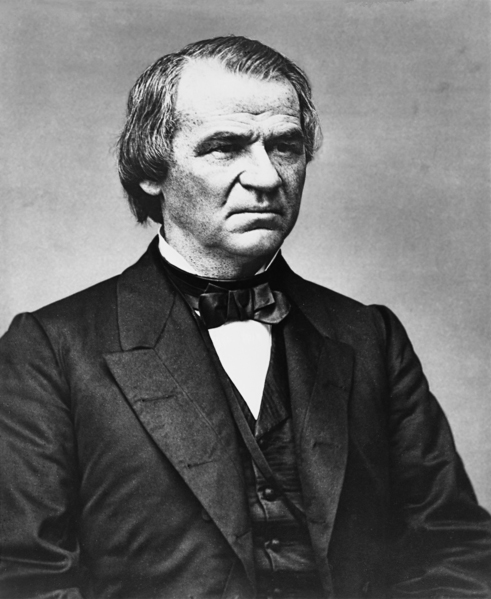

The first great task confronting the victorious North - now under the leadership of Lincoln's vice president, Andrew Johnson, a Southerner who remained loyal to the Union - was to determine the status of the states that had seceded. Lincoln had already set the stage. In his view, the people of the Southern states had never legally seceded; they had been misled by some disloyal citizens into a defiance of federal authority. And since the war was the act of individuals, the federal government would have to deal with these individuals and not with the states. Thus, in 1863 Lincoln proclaimed that if in any state 10 percent of the voters of record in 1860 would form a government loyal to the U.S. Constitution and would acknowledge obedience to the laws of the Congress and the proclamations of the president, he would recognize the government so created as the state's legal government.

Congress rejected this plan. Many Republicans feared it would simply entrench former rebels in power; they challenged Lincoln's right to deal with the rebel states without consultation. Some members of Congress advocated severe punishment for all the seceded states; others simply felt the war would have been in vain if the old Southern establishment was restored to power. Yet even before the war was wholly over, new governments had been set up in Virginia, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana.

To deal with one of its major concerns - the condition of former slaves - Congress established the Freedmen's Bureau in March 1865 to act as guardian over African Americans and guide them toward self-support. And in December of that year, Congress ratified the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery.

Throughout the summer of 1865 Johnson proceeded to carry out Lincoln's reconstruction program, with minor modifications. By presidential proclamation he appointed a governor for each of the former Confederate states and freely restored political rights to many Southerners through use of presidential pardons.

In due time conventions were held in each of the former Confederate states to repeal the ordinances of secession, repudiate the war debt, and draft new state constitutions. Eventually a native Unionist became governor in each state with authority to convoke a convention of loyal voters. Johnson called upon each convention to invalidate the secession, abolish slavery, repudiate all debts that went to aid the Confederacy, and ratify the 13th Amendment. By the end of 1865, this process was completed, with a few exceptions.

Radical Reconstruction

Both Lincoln and Johnson had foreseen that the Congress would have the right to deny Southern legislators seats in the U.S. Senate or House of Representatives, under the clause of the Constitution that says, "Each house shall be the judge of the ... qualifications of its own members." This came to pass when, under the leadership of Thaddeus Stevens, those congressmen called "Radical Republicans," who were wary of a quick and easy "reconstruction," refused to seat newly elected Southern senators and representatives. Within the next few months, Congress proceeded to work out a plan for the reconstruction of the South quite different from the one Lincoln had started and Johnson had continued.

Wide public support gradually developed for those members of Congress who believed that African Americans should be given full citizenship. By July 1866, Congress had passed a civil rights bill and set up a new Freedmen's Bureau - both designed to prevent racial discrimination by Southern legislatures. Following this, the Congress passed a 14th Amendment to the Constitution, stating that "all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside." This repudiated the Dred Scott ruling, which had denied slaves their right of citizenship.

All the Southern state legislatures, with the exception of Tennessee, refused to ratify the amendment, some voting against it unanimously. In addition, Southern state legislatures passed "codes" to regulate the African-American freedmen. The codes differed from state to state, but some provisionswere common. African Americans were required to enter into annual labor contracts, with penalties imposed in case of violation; dependent children were subject to compulsory apprenticeship and corporal punishments by masters; vagrants could be sold into private service if they could not pay severe fines.

Many Northerners interpreted the Southern response as an attempt to reestablish slavery and repudiate the hard-won Union victory in the Civil War. It did not help that Johnson, although a Unionist, was a Southern Democrat with an addiction to intemperate rhetoric and an aversion to political compromise. Republicans swept the congressional elections of 1866. Firmly in power, the Radicals imposed their own vision of Reconstruction.

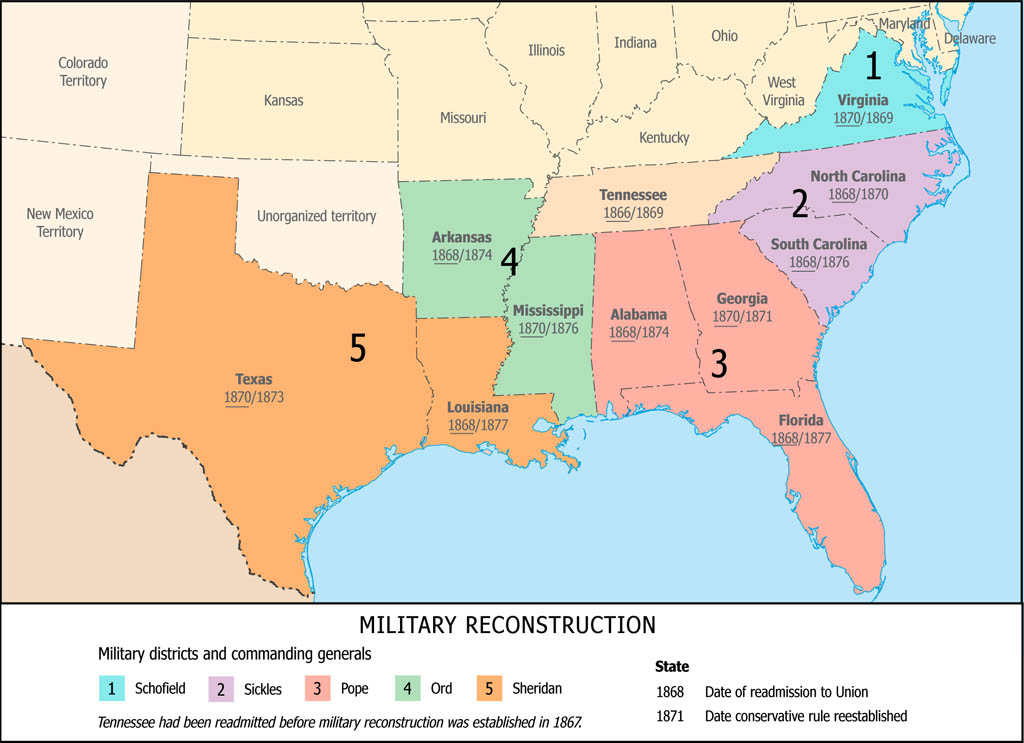

In the Reconstruction Act of March 1867, Congress, ignoring the governments that had been established in the Southern states, divided the South into five military districts, each administered by a Union general. Escape from permanent military government was open to those states that established civil governments, ratified the 14th Amendment, and adopted African-American suffrage. Supporters of the Confederacy who had not taken oaths of loyalty to the United States generally could not vote. The 14th Amendment was ratified in 1868. The 15th Amendment, passed by Congress the following year and ratified in 1870 by state legislatures, provided that "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude."

The Radical Republicans in Congress were infuriated by President Johnson's vetoes (even though they were overridden) of legislation protecting newly freed African Americans and punishing former Confederate leaders by depriving them of the right to hold office. Congressional antipathy to Johnson was so great that, for the first time in American history, impeachment proceedings were instituted to remove the president from office.

Johnson's main offense was his opposition to punitive congressional policies and the violent language he used in criticizing them. The most serious legal charge his enemies could level against him was that, despite the Tenure of Office Act (which required Senate approval for the removal of any officeholder the Senate had previously confirmed), he had removed from his Cabinet the secretary of war, a staunch supporter of the Congress. When the impeachment trial was held in the Senate, it was proved that Johnson was technically within his rights in removing the Cabinet member. Even more important, it was pointed out that a dangerous precedent would be set if the Congress were to remove a president because he disagreed with the majority of its members. The final vote was one short of the two-thirds required for conviction.

Johnson continued in office until his term expired in 1869, but Congress had established an ascendancy that would endure for the rest of the century. The Republican victor in the presidential election of 1868, former Union general Ulysses S. Grant, would enforce the reconstruction policies the Radicals had initiated.

By June 1868, Congress had readmitted the majority of the former Confederate states back into the Union. In many of these reconstructed states, the majority of the governors, representatives, and senators were Northern men - so-called carpetbaggers - who had gone South after the war to make their political fortunes, often in alliance with newly freed African Americans. In the legislatures of Louisiana and South Carolina, African Americans actually gained a majority of the seats.

Many Southern whites, their political and social dominance threatened, turned to illegal means to prevent African Americans from gaining equality. Violence against African Americans by such extra-legal organizations as the Ku Klux Klan became more and more frequent. Increasing disorder led to the passage of Enforcement Acts in 1870 and 1871, severely punishing those who attempted to deprive the African-American freedmen of their civil rights.

The end of Reconstruction

As time passed, it became more and more obvious that the problems of the South were not being solved by harsh laws and continuing rancor against former Confederates. Moreover, some Southern Radical state governments with prominent African-American officials appeared corrupt and inefficient. The nation was quickly tiring of the attempt to impose racial democracy and liberal values on the South with Union bayonets. In May 1872, Congress passed a general Amnesty Act, restoring full political rights to all but about 500 former rebels.

Gradually Southern states began electing members of the Democratic Party into office, ousting carpetbagger governments and intimidating African Americans from voting or attempting to hold public office. By 1876 the Republicans remained in power in only three Southern states. As part of the bargaining that resolved the disputed presidential elections that year in favor of Rutherford B. Hayes, the Republicans promised to withdraw federal troops that had propped up the remaining Republican governments. In 1877 Hayes kept his promise, tacitly abandoning federal responsibility for enforcing black peoples' civil rights.

The South was still a region devastated by war, burdened by debt caused by misgovernment, and demoralized by a decade of racial warfare. Unfortunately, the pendulum of national racial policy swung from one extreme to the other. A federal government that had supported harsh penalties against Southern white leaders now tolerated new and humiliating kinds of discrimination against African Americans. The last quarter of the 19th century saw a profusion of "Jim Crow" laws in Southern states that segregated public schools, forbade or limited African-American access to many public facilities such as parks, restaurants, and hotels, and denied most black people the right to vote by imposing poll taxes and arbitrary literacy tests. "Jim Crow" is a term derived from a song in an 1828 minstrel show where a white man first performed in "blackface."

Historians have tended to judge Reconstruction harshly, as a murky period of political conflict, corruption, and regression that failed to achieve its original high-minded goals and collapsed into a sinkhole of virulent racism. Slaves were granted freedom, but the North completely failed to address their economic needs. The Freedmen's Bureau was unable to provide former slaves with political and economic opportunity. Union military occupiers often could not even protect them from violence and intimidation. Indeed, federal army officers and agents of the Freedmen's Bureau were often racists themselves. Without economic resources of their own, many Southern African Americans were forced to become tenant farmers on land owned by their former masters, caught in a cycle of poverty that would continue well into the 20th century.

Reconstruction-era governments did make genuine gains in rebuilding Southern states devastated by the war, and in expanding public services, notably in establishing tax-supported, free public schools for African Americans and whites. However, recalcitrant Southerners seized upon instances of corruption (hardly unique to the South in this era) and exploited them to bring down radical regimes. The failure of Reconstruction meant that the struggle of African Americans for equality and freedom was deferred until the 20th century - when it would become a national, not just a Southern issue.

Source Citation:

"An Outline of American History," United States Information Agency. https://archive.org/details/OutlineOfUSHistory/page/n147/mode/2up