22 Dec. 1841–7 Feb. 1891

August Heinrich Christian Julius Bonitz, editor and publisher, was born in Zellerfeld, Hanover, Germany, the fourth child of Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Bonitz and Dorothea Louise Schalitz. His father had been superintendent of a silver and copper mine, the "Dorothea," in the fabled Harz Mountains of northern Germany, a position held by his father and grandfather before him.

Before his seventeenth birthday, Julius emigrated with his family from Bremen to the United States, arriving in Baltimore aboard the barkentine Vieland on 22 June 1858.

The newcomers hardly had time to adjust to their new environment before the Civil War erupted. For some unrecorded reason, Bonitz had developed a loyalty to the Southern cause, and for three years and eight months he served in the ranks of the Confederacy.

After the war, Bonitz settled in Goldsboro, where he established a mercantile business. His venture was fairly prosperous until he purchased a sizeable farm near Goldsboro, when the combined operations brought disastrous financial consequences. According to his own account, his capital was reduced to the sum of five dollars realized from the sale of his watch.

Bonitz's next undertaking was the recruiting of contract labor to work in the naval stores industry then centered in the pine forests of the Carolinas. As funds became available he started a brickyard, but once again his business collapsed, when a cold rain (and a lack of firewood, which he could not afford) ruined a large kiln of two hundred thousand brick. With considerable ingenuity, he was able to trade his mountain of partly cured brick for the tangible assets of a defunct newspaper, the Goldsboro Star. He moved the press and type to an old printing office building, and shortly thereafter the Daily Rough Notes made an unheralded appearance on the Goldsboro scene.

The old Whigs and the old Democrats united in 1868 to form the Conservative party, as the Whigs objected to being called Democrats. Bonitz's Daily Rough Notes was solidly aligned behind the Conservatives, and he vehemently opposed the military despotism and black rule of the radical Republicans. During the election period he was joined in his newspaper enterprise by Major William A. Hearne and Captain Swift Galloway, a pair of like-minded acquaintances. Despite their efforts, the scalawag, carpetbagger, and black elements that had combined to support a fellow editor, William W. Holden, were able to defeat Conservative Thomas Ashe in the race for governor.

Following the election the paper's name was changed from the Rough Notes to the Messenger. The triumvirate of associates did not endure for long: after a few weeks Hearne and Galloway withdrew, leaving Bonitz in sole control.

Keeping the Messenger viable was a struggle that demanded the utmost effort from Bonitz during the chaotic era of Reconstruction. He needed a twenty-four hour notice to produce even one dollar of his printer's overdue wages. And an even greater calamity lay ahead: on the night of 4 Sept. 1869, a fire raged through the business district of Goldsboro, leaving most of it in smoking ruins. The office and the equipment of the Messenger were destroyed completely. But Bonitz was far from defeated. Salvaging a handful of type and borrowing an amateur hand press, he brought out an "extra" two days after the fire in which the conflagration was described in all its spectacular detail. His "shop" was the open air beneath the boughs of an old sweet gum tree, with Bonitz setting the type and his foreman, W. H. Collins, operating the press. Readers gave him support by paying for their subscriptions in advance, and after a lapse of only four days, the Messenger resumed publication as a weekly, and occasionally semiweekly, paper.

Bonitz continued to publish his paper almost single-handedly, reporting, editing, soliciting advertising and doing other necessary chores. Gradually, as the Messenger prospered, he was able to lighten his labors by additions to his staff. Thus he was able to find the time to publish a sixty-eight-page booklet with a title almost as long: "The Murder of the Worley Family in Wayne County, N.C., and the Arrest, Trial and Execution of Noah Cherry, Robert Thompson and Harris Atkinson."

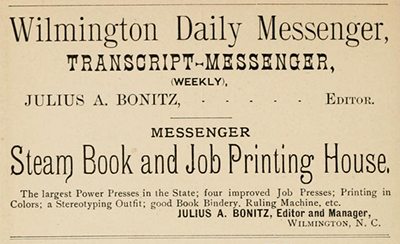

In June of 1887, with the encouragement of businessmen of Wilmington, he moved and became editor and publisher of the Wilmington Messenger in what was then the chief city of the state. Continuing his fervent support of the Democratic party in his editorial columns, he also advocated strongly the goal of wide public education, the achievement of which was yet some years in the future.

Bonitz's health had begun to fail before his move to Wilmington, and he died there. He was first buried in Wilmington, but his body was later moved to Willowdale Cemetery in Goldsboro, where it lies under an impressive and lengthily inscribed monument.

Bonitz was married on 22 Apr. 1873, in Lynchburg, Va., to Delia Alice Berndt, who was born 3 Jan. 1852 and died 23 Feb. 1931 in Oxford. They had four children.