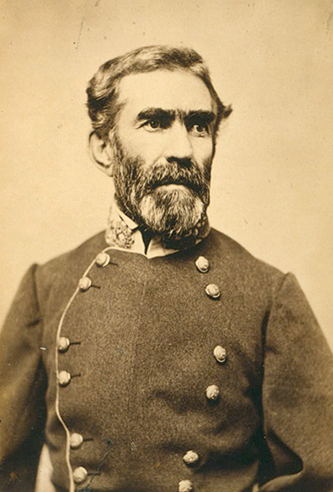

22 Mar. 1817–27 Sept. 1876

Braxton Bragg, a professional soldier during the Mexican War, and commanding general of the Army of Tennessee of the Confederate States of America during the Civil War, was born in Warrenton, NC. He was one of six sons of Thomas and Margaret Crossland Bragg. He had five brothers: John and Thomas, who were lawyers and politicians; Alexander, an architect; Dunbar, a Texas merchant; and William, who was killed in the Civil War.

Bragg's father moved to Warrenton in 1800 to be a carpenter and practiced the trade until he married Margaret Crossland in 1803. Thomas became a contractor, eventually acquiring a two-story brick home in Warrenton and enslaving about 20 people. The family's reputation in Warrenton was mixed, and this was reflected in a letter from Congressman David Outlaw to his wife, dated Aug. 1, 1848: Outlaw expressed the hope that the people of Warrenton would properly honor Braxton upon his return from the Mexican War, adding that Colonel Bragg "must in his heart despise those who were formerly disposed to sneer at his family . . . as plebians."

Braxton Bragg followed his elder brothers to Warrenton Academy, and with the help of Senator Willie P. Mangum secured an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, where he was graduated near the top of his class in 1837.

As a lieutenant of artillery, he was posted to Florida and participated in the Seminole War, but his health declined and he was sent home to recover. Upon his return to active duty, he acquired a mixed reputation as an intelligent and hard-working but quarrelsome officer. Ironically, during this period, he formed close relationships with two other young officers, George H. Thomas and William T. Sherman, both of whom would later be instruments of his defeat on Civil War battlefields.

He placed his career in jeopardy in 1844–45 with a series of articles in the Southern Literary Messenger in which he attacked the entire army administration, reserving his harshest criticisms for its commander, General Winfield Scott. While his critiques may have been valid, they led to his arrest and court-martial on charges of insolence and disobedience. He was found guilty of disrespect for superior officers and received official reprimands and suspension of rank and command for a period of two months. His appeal failed to get the sentence reversed, and though he had powerful friends in both the government and the army, his career appeared blighted. Then, in June of 1845, he and his company were ordered to join General Zachary Taylor's army, for the protection of Texas against Mexico.

His service during the Mexican War was noteworthy; he was twice breveted and then promoted to the rank of captain of artillery. At Buena Vista, he personally directed his battery in a series of actions that broke a Mexican attack and led to an important American victory. He was breveted lieutenant colonel and returned to the United States aa a popular hero, the man who, according to popular legends, had stopped the Mexicans with "a little more grape."

In 1849, while assigned to duty in New Orleans, he met and married Louisiana heiress Eliza Brooks Ellis. The couple spent the next six years at various military posts, but neither Bragg nor his wife was satisfied with the necessity of living on the frontier. On Dec. 31, 1855, Bragg resigned his commission after a dispute about assignments with Secretary of War Jefferson Davis; in February 1856, he bought a sugar plantation near Thibodaux, La. According to the 1860 U.S. Federal Census, about 110 people were enslaved by Bragg and worked his plantation during the time he and Eliza lived in Thibodaux. Successful as a planter and enslaver, Bragg also became commissioner of public works, designing and constructing drainage and levee systems.

As the secession crisis approached, Bragg became reluctantly involved in preparations for war. He had not favored secession but in 1861 told his friend Sherman that sectional bitterness had become so strong that it might be better if the South departed in peace.

Bragg became a major general in the Louisiana militia and was commissioned a brigadier general in the Confederate Army, commanding coastal defenses in the region from Pensacola, Fla., to Mobile, Ala. In January of 1862 he was promoted to major general, and one month later he asked for the transfer of his command to the north, where he felt it would be needed. His request was granted, and he moved to Corinth, Miss., joining the army of General Albert Sidney Johnston. From Corinth, the army moved to Shiloh, with Bragg in the dual role of commander of the Second Corps and chief of staff. He was noteworthy at the Battle of Shiloh, was rewarded with a promotion to general, and on June 27th relieved General Pierre Beauregard as commander of the Army of Tennessee.

From his promotion onward, Bragg's performance as a general waned, as did the fortunes of the Confederacy. Bragg lacked the qualities essential for success in a field command position. Often opening opportunities through bold and sometimes resourceful action, he almost invariably lacked the persistence to exploit advantages. He was never able to win the loyalty and trust of his own subordinates due to his poor temper and combative personality. At one point, after the Stone River debacle, they openly called for his resignation. Still, Davis stood by him until the disaster at Chattanooga compelled his replacement in December 1863.

Following his removal from command, Bragg was summoned by Davis to Richmond, nominally as commander in chief but actually as military adviser to the Confederate president. Bragg accompanied Davis on the trip south in 1865, was captured May 9th, and received a parole.

The U.S. Government confiscated Bragg’s prewar home during the war, due to his ownership of enslaved people and alignment with the Confederacy. This forced him and his wife to relocate to Alabama after his parole in 1865. He worked in a number of fields after the Civil War, including a brief stint an agent in a life insurance company and railroad inspector. Bragg collapsed in Galveston, Texas on September 27, 1876, and died fifteen minutes later at age of 59.