3 Oct. 1841–1 July 1863

Henry ("Harry") King Burgwyn, Jr., one of the youngest colonels of the Civil War, was born at Jamaica Plains, Mass., in the ancestral home of his mother, nee Anna Greenough. He was the first son of Henry King Burgwyn, planter of Thornbury, Northampton County, and a descendant of John Burgwyn. A younger son of Henry King, Sr., was William H. S. Burgwyn. Harry received his early education from private tutors at his father's plantation and at academies in the North. Although not an official student, he was sent to West Point to study privately at age 15. His tutor at West Point was Captain John Gray Foster, who later commanded the Federal Forces in Eastern North Carolina as a Union major general. Burgwyn was not admitted to the US Military Academy at Westpoint and instead studied at The University of North Carolina from which he graduated in 1857 with a Bachelors of Science. He then enrolled at the Virginia Military Institute. At VMI, he was one of the cadets detailed to guard John Brown prior to execution. Graduating in April 1861, he left the institute with a letter of recommendation from Professor T. J. "Stonewall" Jackson.

A few weeks after the secession of North Carolina, Burgwyn found himself with a major's commission. After a recruiting trip to Western North Carolina, he was assigned to command a "camp of instruction" near Raleigh, where Confederate volunteers were gathering to be formed into fighting units. At nineteen he was elected lieutenant colonel of the Twenty-sixth North Carolina Regiment, with a commission dated 27 Aug. 1861. The colonel of the Twenty-sixth was Zebulon B. Vance. Vance supplied the esprit for the regiment, Burgwyn the military discipline and skill. Until February 1862, the regiment was on Bogue Island as part of the defenses of Fort Macon. After the fall of Roanoke Island, the Twenty-sixth was ordered to New Bern. It took a conspicuous part in the Battle of New Bern, 14 Mar. 1862, being heavily engaged for three hours and retreating, according to enemy reports, only when its ammunition was exhausted. Burgwyn was praised by Vance for "great coolness and efficiency" during the Confederate retreat and was said to have been the last man to cross Brice's Creek to safety. Prior to this first action, Burgwyn had been unpopular because of his military rigor; thereafter he enjoyed the respect and confidence of the citizen soldiers.

In June 1862 the Twenty-sixth was ordered to Virginia, where it took part, although not a conspicuous part, in the Seven Day's battles outside Richmond, attached to General Robert Ransom's brigade. In the late summer of 1862, Vance resigned to become governor. Ransom objected to Burgwyn's promotion, declaring that he wanted no "boy colonels" in his brigade. However, the regiment twice voted its confidence in Burgwyn, and General D. H. Hill sustained the appointment. Thus Burgwyn became colonel at the age of twenty; while it is impossible to determine with certainty who was the youngest colonel in the war, he was one of the youngest regimental commanders on either side, especially at that early point in the hostilities. Following his promotion, the Twenty-sixth was transferred from Ransom's brigade to that of James Johnston Pettigrew. Pettigrew and Burgwyn were both modest, intellectual, ascetic, and completely dedicated to their duties. "Imitating each other," according to one veteran, "they reached the highest excellence possible of attainment" in soldierly traits. From August 1862 to May 1863 the brigade was engaged in a number of actions against Federal troops in Eastern North Carolina, most notably at Rawle's Mill in Martin County in November, at the Second Battle of New Bern in February, and at Blount's Creek in Beaufort County in April. In all these actions the Twenty-sixth performed with distinction, usually against larger Federal forces.

In May, Pettigrew's brigade was incorporated into the Army of Northern Virginia in time for the campaign into Pennsylvania. The stout yeomen of the Twenty-sixth Regiment, under the leadership of Burgwyn and Pettigrew, had reached a peak of morale that made them, as subsequent events were to show, the most distinguished unit of North Carolinians in the war. Henry Heth's division, of which Pettigrew's brigade was a part, became heavily engaged on the first day of Gettysburg, 1 July. During the morning, the Twenty-sixth lay under fire with an excellent view of the position it was to assault in the afternoon. At two o'clock, Pettigrew's brigade was ordered forward. Bearing the brunt of the assault, Burgwyn's men charged across a creek (Willoughby Run) and up the wooded slope of McPherson's Ridge, overrunning and driving off three lines of Federal artillery and infantry, including the famous "Iron Brigade." This twenty-minute action was one of the most heroic and bloody charges of the war. Out of 800 men, the Twenty-sixth reported 588 killed and wounded, which has been judged the heaviest loss in a single regiment on either side during a single day of the war.

As the Twenty-sixth engaged the second Federal line, the eleventh man carrying the regimental colors was shot down. Burgwyn grabbed the flag and within seconds received a rifle ball in the side, which passed through his lungs. He died within two hours, aged twenty-one. "His loss is great, for he had but few equals of his age," wrote an officer who reported Gettysburg to Governor Vance. Burgwyn was buried under a walnut tree near Gettysburg with a guncase for a coffin. After the war the remains were retrieved and reinterred in Oakwood Cemetery, Raleigh. A Marine Corps camp in Alabama was later named for him.

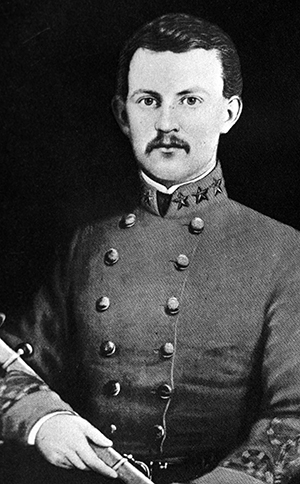

An Episcopalian, Burgwyn died unmarried. He was described as slender and handsome, with brown hair and moustache, quick of movement, and with an authority unusual for his age.

Burgwyn was a conspicuous example of the young men of the antebellum planter class, who were nourished on southern patriotism and the military virtues and who, in the words of Eugene Genovese, "selflessly fulfilled their duties and did what their class and society required of them."