See also: Communist Workers Party; "Death to the Klan" March; Gastonia Strike; Scales Trial.

Following the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia in 1917, American sympathizers founded several communist parties. The two largest ones merged in 1921 to form what came to be called the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA). There was no organized body of communists in North Carolina for a number of years to come. In 1920, however, during the "Red Scare" after World War I, an army officer in Greensboro informed the director of U.S. Military Intelligence that authorities were making an effort to deport an unnamed, jailed member of the Communist Labor Party. The same report alleged that the U.S. Department of Justice had several prominent North Carolinians "under consideration" for possibly "flirting with radicalism."

In 1929 the National Textile Workers Union, an affiliate of the CPUSA, organized a violent but unsuccessful strike at the Loray Mill in Gastonia. The fruitlessness of this initial foray of the CPUSA into the South was, in the words of one of the strike's organizers, due in large part to the party's failure to recognize and exploit the region's "peculiar conditions."

The CPUSA maintained only a meager presence in North Carolina after the Loray Mill strike, although for several years in the early 1930s Charlotte was the headquarters for the party district comprising North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and Georgia. Army intelligence reports credited the Charlotte headquarters with fomenting industrial unrest in the Carolinas, and in 1934 a strike by textile workers in Burlington, N.C., led to the direct involvement of the party's legal arm, International Labor Defense, in defending strikers accused of plotting dynamite bombings.

Despite its role in the Gastonia and Burlington strikes, the CPUSA realized scant success in the organization of labor in North Carolina. Nor did it make notable progress in increasing its numbers in either white or African American communities, although Black citizens were especially targeted for recruitment. An army intelligence report of 1940 related that the state headquarters of the CPUSA was in Greensboro, that party membership was divided mainly into textile workers and "agrarians," that little had come of efforts to control textile unions, and that a recent attempt had been made to "enlist the Negro population." In 1945, when membership in the Carolinas district numbered only 53, the party was beginning to make progress in several unions, primarily one representing tobacco workers at the R. J. Reynolds plant in Winston-Salem.

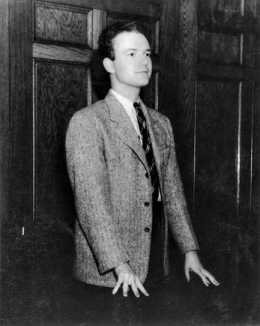

In the immediate postwar period, the party gained some members among students and faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This growth was due mainly to the efforts of Junius Irving Scales, a Greensboro native, chairman of the Chapel Hill branch of the CPUSA, and later (1948-56) head of the party's organization in North Carolina and South Carolina. But as Cold War tensions began to intensify, party membership sharply declined. In 1955 Scales was tried and convicted under the Smith Act of 1940, which made it a crime to be a member of any group advocating the violent overthrow of the U.S. government. Scales served 14 months before President John F. Kennedy commuted his sentence.

The CPUSA in North Carolina, as elsewhere, was essentially moribund for decades following the Soviet invasion of Hungary and revelations of Joseph Stalin's crimes, events that led Junius Scales to resign from the party in disillusionment in 1957. Although such groups as the Communist Workers Party (which achieved notoriety in 1979 when five members were killed in a confrontation with the Ku Klux Klan in Greensboro) maintained a presence in the state, the CPUSA was virtually extinct. In the mid-1990s the party began to rebuild its organization in the Southeast, including in North Carolina. By that time, communist regimes had fallen in the Soviet Union and throughout Eastern Europe, and communism was perceived by most Americans as no longer constituting a serious threat. In addition, the CPUSA sought to increase its appeal by abandoning its traditional antipathy toward organized religion, as well as maintaining a publication and a website called the People's Weekly World. Even so, progress in recruitment was slow; in the early 2000s there were only about 100 members in the Carolinas district.