The East-West rivalry is the name for a particularly potent form of sectionalism that has been a major factor in the political, social, and economic development of North Carolina. The state's varied geography shaped the character of incoming European settlements, and there soon emerged distinct regions reflecting differences in nationalities, languages, and religions. Conflict rooted in regional identity was strong, usually developing around political or economic issues and events, the collection and distribution of taxes, and representation in colonial or state government.

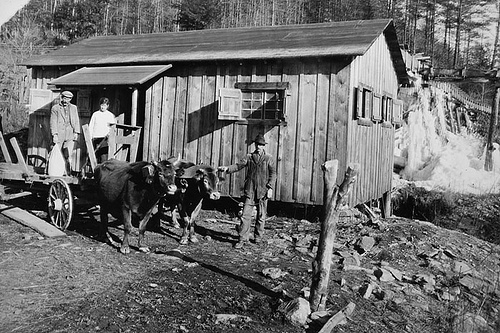

Initial rivalries and jealousies existed between the northern and southern parts of the colony, but these were soon followed by those between east and west. The conflicts stemmed primarily from cultural differences born of economic realities and self-interests. Western settlers owned mostly small farms and businesses, while those in the east often had large plantations and commercial enterprises that afforded them more wealth and power. Additionally, westerners usually had few slaves or none at all, whereas many leaders in the east were large slaveholders. The east had wide, shallow, slow-moving rivers and streams suited for river transportation, while the West's narrow, fast-flowing streams limited river traffic but promoted the development of mills and waterpower.

In the years after the Revolution, North Carolinians in the Piedmont and the west prospered and their political aspirations grew. By 1830 more than half of the state's population lived west of Raleigh; the state government, however, remained in the control of the eastern elite, empowered by its advanced political organization and economic status. The 1776 state constitution had mandated equal county representation and included strict property qualifications for officeholders, which put the westerners at a disadvantage. The constitution also contained no provision for amendment, so only a constitutional convention called by the legislature could revise the document.

The climax of this sectional dispute came in the 1830s, when many westerners embraced the Whig Party as their vehicle to gain political power. Using the new campaign tactics of the time, North Carolina Whigs, led by canny politicians such as David Swain, swept to ascendancy in the state government and engineered a constitutional convention in 1835 that equalized representation in the General Assembly. Provisions were adopted and later ratified by the people for reapportionment of the legislature, including abolition of borough representation and partial removal of religious qualifications for voting and office holding. The 50-acre requirement to vote for state senator was retained, but all adult white male taxpayers could vote for governors and representatives in the legislature. The Whig era was a period of reform and modernization, especially in the areas of government-subsidized public education and internal improvement, a source of special concern to those residing in the undeveloped interior of the state.

The Civil War, like the Revolution, often fostered in North Carolinians a tendency toward social polarization and occasional violence. Again, westward communities were more apt to be antigovernment-in this era, consequently, pro-Union-although even the west was home to several Confederate strongholds. At times, however, this social division assumed more of a class conflict than a true regional dispute. Increased settlement in rural areas, by people of varying economic status and political allegiances, had begun to blur sectional lines that in earlier times had been more readily apparent.

The distinctly east-west friction subsided greatly in the twentieth century, as differences between North Carolina's geographical and cultural identities diminished while new divisions arose. A kind of informal rotation pattern occurred for a time, leading to the election of governors, U.S. senators, and other political leaders from both east and west. A new brand of sectionalism emerged in the state during the mid-twentieth century. No longer based on an east-west axis, modern sectionalism is grounded in rural-urban differences. In the 1960s the state's expanding cities demanded a stronger political voice, which resulted in the creation of new voting districts that gave Piedmont and Mountain citizens greater representation in the legislature. The one-person-one-vote rule established by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1962, which emphasized the population size of particular voting districts, also greatly increased the political power of urban areas. In addition, the success of the civil rights movement during this period caused the delineation of some districts to be based on racial demography. This new sectionalism also exhibited class divisions as urban "modernists," rooted primarily in the so-called Piedmont Urban Crescent, clashed with rural "traditionalists" in their quest for political and economic equality.

Many remnants of North Carolina's sometimes volatile east-west rivalry remain. For example, the eighteenth-century conflict and eventual compromise between the eastern and western regions determined the locations of both the state's capital and its first major university. The site for the capital city of Raleigh was arrived at through much east-west political wrangling; it was ultimately selected, according to both legend and historical research, by its proximity to a tavern that served an excellent rum punch. The location of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill was likewise a compromise between eastern and western discourse.